‘Unli’ rice unsustainable

Rice, a political commodity and the staple of Filipinos and most Asians, is the cheapest on the dining table compared with viands.

Most Filipinos cannot consider their meal complete without a cup of rice. Some restaurants now offer unlimited rice to customers. This shows how big Filipinos consume rice.

Article continues after this advertisementIn Japan, rice is considered a valued commodity because it is not only consumed as cooked rice but is also used to make sake. Other Asian countries use rice instead of wheat to make noodles. In our country, we use rice to make products like kakanin (rice cakes).

Indica variety

The Philippines like our Asean neighbors plants the indica variety (long grain) while Japan, Korea and Taiwan use the japonica variety (medium to short grain).

Article continues after this advertisementSixty-percent of the country’s population, especially those in the rural areas, depends on the rice industry for livelihood.

Rice consumption increases if the economy is bad as this is the most affordable food to fill up the stomach and decreases as the economy improves because people tend to eat more of dishes like meat, vegetables or fish.

Taken for granted

Rice is usually taken for granted because it is always available on the market. A customer would ask a waiter to put in a doggy bag leftover dishes but uneaten rice, more often than not, would be left on the table to be disposed of later by the restaurant.

If consumers are educated on how hard it is for farmers to till the soil so they can plant palay (unhusked rice) and on the process it takes to produce rice, attitudes toward rice would change.

That change would also save us millions of dollars spent on importing the staple to fill the gap between production and consumption.

Top importer

We boast that we taught our Asian neighbors the science of planting rice through the International Rice Research Institute and University of the Philippines Los Baños. Most of them are now exporters of rice but we still remain an importer. We were rated the No. 1 importer in 2008 and have stayed on the list of Top 5 importing countries.

The rice industry in the country is deteriorating instead of advancing because the real problems are not being properly addressed. The economies of neighboring countries, especially Vietnam and Thailand where we buy most of our imports, continue to grow partly due to their rice exports.

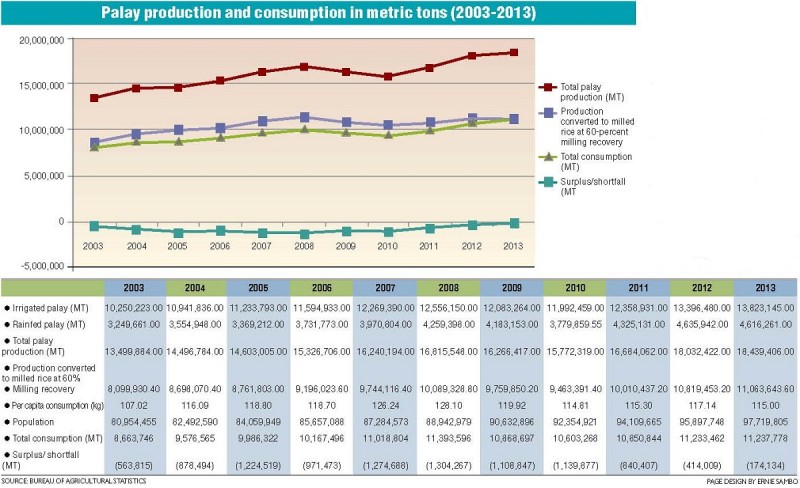

Why do we need to import rice for our buffer stock when every year, according to the Department of Agriculture, production has been steadily increasing?

Channels

For a better understanding of the rice industry’s situation let’s start by looking at the channels or stages that palay passes before it becomes cooked rice on the dining table.

Farmers till the soil, plant palay and harvest it.

Assembly traders consolidate the farmers’ produce on the farm to sell either directly to a rice mill or palay trader as the farmers have limited logistics to transport their produce.

Palay traders buy palay either from the farmers or the assembly traders. Most of their warehouses are located near production areas. They buy and later sell the palay to rice mills.

Millers process the palay by removing the husk and polishing it to make the rice white.

Haulers transport the rice from the mill site to wholesalers (real rice trader).

Market wholesalers keep big stalls to stock some inventories.

Retailers sell directly to consumers.

Price fluctuation

The price of rice varies depending on the months—whether it’s the harvest season or off-season harvest (lean months). This is one factor that we should understand. Prices are low in the harvest season but gradually go up during the lean months.

In the harvest season, dried palay from the farm are milled immediately and some are stored for milling during lean months. It is for this reason that prices of rice are low as fewer costs are incurred during processing.

After the end of the harvest, most of the excess palay that were not milled are stored in warehouses, resulting in additional costs when they are milled into rice. These are the cost of money (interest), shrinkage (weight is reduced during storage) and cost of storage.

These add to the price of the rice milled from long-stored palay compared with the palay milled during the harvest season. For every sack of palay milled during this period these cost factors are included until the next harvest comes in.

The variety, degree of milling (well-milled or regular), percentage of broken and whether it’s aged (laon) or new also determine the pricing.

Rising fuel and electricity costs affect all the channels in the industry—from production to delivery to markets, depending on the province and city.

Prices in major producing provinces are cheaper than in urbanized areas as the transport cost in the provinces is lower.

Antiquated

Inefficiency caused by the use of antiquated equipment often results in higher rice prices, depriving the farmers of a better price for their palay.

Why are millers not improving or updating their equipment?

The first and foremost reason is government policy. Millers want to have a definite government policy (i.e. rice importation) before investing in equipment, which entails big capitalization.

Millers, as much as possible, want to operate 24/7 to enable them to recoup their capital but with confusing government policies and direction there are times when the mills operate only eight hours a day due to smuggling.

Seldom or never has any government agency mentioned any support for this dying sector. Warehouses, which store the produce of farmers because the government doesn’t have enough storage space, are sometimes raided for alleged hoarding.

It is a foolish business decision to hoard palay or rice since this commodity should be fast-moving. The more you mill the faster you recover your capital.

Capital, labor-intensive

Milling is both capital- and labor-intensive. It also requires personal supervision by the owner because the palay that is brought into warehouses for milling comes in different qualities—from high-moisture content to ready-for-mill quality.

Variety also plays a vital role. Different varieties look similar but the differences depend on what the farmers planted for the season and on the regions they came from.

Price depends on these two major factors. If the owner just lets an employee classify palay, he might end up milling bad grain or go bankrupt as the palay that should be classified as class C is classified as class A through negligence or cheating.

Worst if palay is stored as it is only when the grain is milled that its quality comes out. A high price for palay and rice is not beneficial to the rice milling industry and the country as businessmen will be needing more capital to produce the same quantity as when the prices of palay and rice are lower.

Misconception

It is therefore a misconception that a higher price means more profit since the higher price limits your capitalization, thereby reducing profit.

Although rice is part of agriculture, its dynamics are different from other produce. Unlike vegetables, which can be sold as soon as these are harvested, palay undergoes a process before it is called rice.

Post-harvest facilities

The lack of post-harvest facilities like mechanical dryers and the use of antiquated milling technology are the biggest factors that contribute to unnecessary wastage, and low palay and high rice prices.

The national average recovery of the antiquated rice milling industry is only 60 percent compared with 66 to 70 percent for modern rice mills. What we are importing is not the shortfall in production but the wastage in the post-harvest segment.

If we use modern technology, we will be self-sufficient and might even have a surplus for export, based on data on palay production and the per capita consumption of 115 kilograms. Our farmers are very able and efficient compared with their counterparts in the Asean.

The government, through the National Food Authority (NFA), sells rice at a subsidized price. The NFA’s mandate is to help farmers by having a price support mechanism for palay and by subsidizing the price of rice for the poorer sectors of our society.

If the private sector offers a higher price for palay and the NFA buys only a small volume of the country’s harvest given its buying price is pegged at P18/kg, farmers would rather sell to the private sector for a better price.

NFA buffer stock

As the agency needs to stabilize the price and supply, it resorts to importation for its buffer stock in this kind of situation.

Consumers should be made aware that the price of NFA rice is subsidized and in no way it is possible for the private sector to produce rice at given price of palay at, say, P18/kg and rice at P28/kg retail.

Mechanisms should be put in place for the sale of NFA rice so that the main beneficiary are the poor.

At present, anybody can go to the market and buy NFA rice. Thus, even the rich, who don’t need the subsidy, benefit from it.

Rich enjoy subsidy

For instance, some people who live in exclusive villages separate their rice consumption from their domestic helpers. Instead of buying commercial rice for helpers, they buy the government-subsidized rice. As a result, the government is also subsidizing the upper class. The purpose of the subsidy is to help families who cannot afford the commercial rice.

Some companies also take advantage of this scheme as they would buy NFA rice for the rice allowance of their employees.

Byproducts

We should take note that the beneficiaries of this industry are not only the consumers but also the poultry, hogs and fisheries sectors. Rice bran (darak), a byproduct of milling palay, is used as feeds for the animal and fishing industry.

Breweries also use brewer’s rice (binlid), another byproduct, for brewing their beer. Lately, the husk (ipa) is being used as fuel for biomass plants to produce electricity.

Unabated rice smuggling has also adversely affected the industry. It eats into the income of farmers because it lowers the prices of their produce. Smuggling deprives the government of revenue needed to support the agriculture sector.

Also adversely affected are other allied industries since there is no byproduct to speak of if there is no milling.

Smuggling came into the picture when importation, exclusively done before by the NFA, was opened to the private sector. Permits to import were recycled several times until such time that they are needed by the Bureau of Customs. As this crime constitutes a major blow to the industry and the economy, a proposal to consider this economic sabotage, thereby making it a heinous crime, should be supported.

Stopping smuggling, improving post-harvest facilities, avoiding wastage on the table, eating only what we need and doing away with “unli” rice at restaurants will help make us self-sufficient in rice.

(Joji Co is president of Philcongrains, an association of rice millers founded in 1950, and director of Samahang Industriya ng Agrikultura, an umbrella organization of federations and sectors in the agriculture industry.)