Some men, past the borders

INQUIRER.net stock photo

Ivan said he’s 27 — turning 28 in November — but he was cautious not to show any sign that would make me doubt him. He looked younger than I thought.

I first talked to him while he was taking a cigarette break. We just passed the Cambodian border and we were waiting for a tour guide to give our passports back.

Article continues after this advertisementI assumed he could speak English. He was the only passenger who didn’t look Asian.

When are we getting our passports back?

I skipped the usual introduction and pretended that it was not our first conversation. I don’t know, he answered. The pit stop was like a cafeteria with red and green monobloc tables and chairs. It was too late for lunch but too early for dinner. I also wanted to try, for the first time, Cambodian food.

Article continues after this advertisementI asked Ivan to join me at my table and he said yes. He had a can of Angkor beer and called it liquid lunch. My meal was sad and depressing. It didn’t represent Cambodian cuisine well at all.

It was early in the evening when we arrived in Phnom Penh. The air was still humid and filled with the cacophony of sound from tuk tuks and other vehicles everywhere.

But I already missed the last trip to Siem Reap.

I was planning to ask a tuk tuk driver for a recommendation of a cheap hostel. I wished Ivan would offer and he did. He had an extra reservation for a friend who missed the trip.

It was a boutique hostel with a small bar — the usual choice of backpackers — with dorm-type rooms. Six beds for six weary travelers.

But it was the lean season so we had the room just for the two of us.

Ivan did not change clothes. He took a book from his backpack and said he’ll go out to read and probably drink beer again. I said I’d follow. He’d be waiting, he replied.

*

He told me that he was from Manchester in the U.K. and he was teaching English in South Korea. He was on a sabbatical leave to travel around Asia — starting in Thailand, proceeding to Vietnam, and ending in Cambodia.

I mentioned I’m a writer. Or at least trying to be one again but the muse was quite elusive.

What do you write? He seemed curious.

Poetry. And my fear of not writing again echoed with the last syllable of the word — poetry.

I noticed that the name “Lee” was written on the edge of the Marquez book which he intended to read but was left untouched beside the ashtray.

There was a tentative question in my mind. I wanted to ask who Lee was but settled to reading the name again. He saw me.

This is not mine, he said.

I like that author, too. Maybe we were two Estebans drifting, wanting comfort, and searching for islands we can call our town, I said.

He grinned.

After his third Angkor beer, I knew Lee. Or at least from Ivan’s stories, I seemed to know him. Ivan was supposed to be in this trip with him. And perhaps, I’d know more when the night is almost over and I’d rush to drink the last bottle of beer.

Ivan asked what I was planning to do in Phnom Penh. I told him that I would be leaving in the morning to go to Siem Reap. I’m only here to see the Angkor temples. He wanted to go with me but he was planning to visit the Khmer killing fields in the morning. I made arrangements and decided to go with him to see the killing fields and leave for Siem Reap in the evening.

I tried to reach for the book but he stopped me. He held my hand with a slight grip — a stranger’s hand pressed on mine against a cold glass table. I was a little embarrassed and wanted to apologize. But before I was able to say something, he said sorry.

I understood that there was no reason to ask why and just nodded slightly. There was no need to insist, too.

*

I went back to my room and he followed me sooner than I expected. He was just behind me and when I opened the door, his hand reached for the knob. I turned around — and for the first time I had the chance to look at his face intimately.

He moved closer and kissed me. But his kiss had no life. It was a proposition of some sort, but less than what I anticipated — only the taste of beer from his lips had more promise.

I woke up the next day with a mild hangover and Ivan was not there. He was not in the shower and his backpack was missing. I went to the reception and asked a young lady where Ivan was or if she had seen him. She replied in strong Khmer accent and the only English words I understood were check out, morning, and Ivan.

For a brief moment, I wished he left something. A thank you note or a wish for safe travel. But what for? There was no need to change plans anymore. His urgent leaving became an unexpected yet welcome palliative.

The air was humid and the stark yellow sun made everything clear outside — a group of monks in orange civara, walking around, asking for the usual morning alms.

_

Lyde Sison Villanueva writes poetry and creative nonfiction. He graduated from Silliman University and was a fellow of the institution’s national writing workshop. He is currently working to accomplish his graduate degree in creative writing at De La Salle University. Constantly traveling, he also indulges in documenting his adventures through photography.

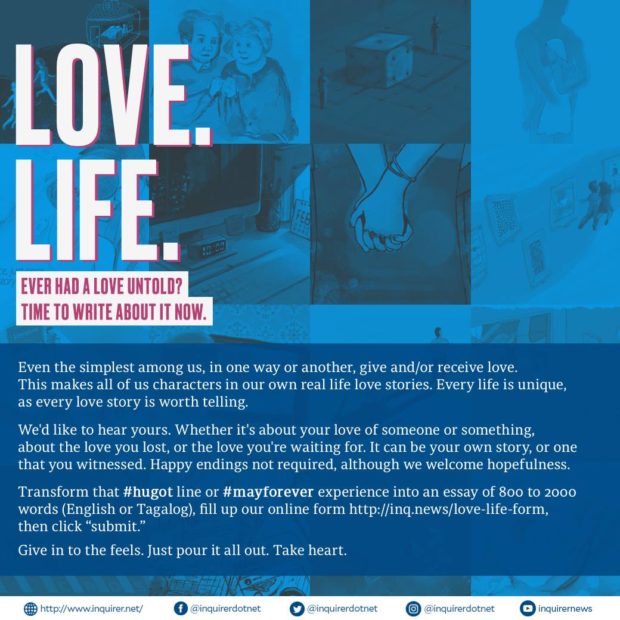

INQUIRER.net/Love.Life.

RELATED STORIES: