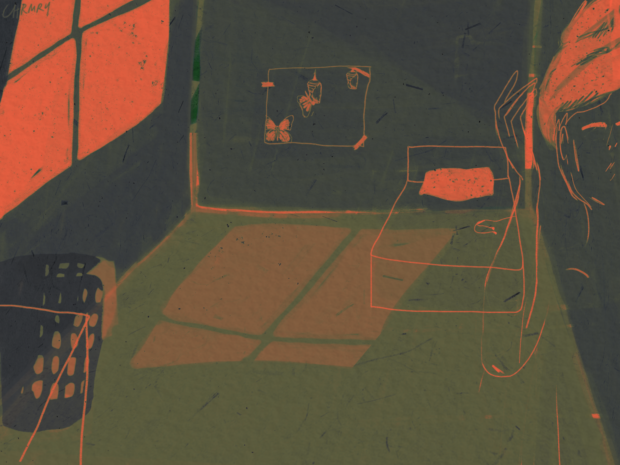

Year of atrophy

“Year of Atrophy” by and courtesy of Chermary Panga

For something to atrophy, it must first reach a certain altitude, like knowing warmth before distinguishing cold, or joy before grief. In language, I suppose atrophy comes after passing the periphery of form, when the curve circles back to its bare components, the phrases and the words: an undoing.

* * *

The end of the decade began at a literal high. In January, I spent a week-long trip in the mountains up north, high as a kite. The scenery was serene and so was I. But as the bus spiraled down the mountain road, the high, likewise, spiraled down. At a rest stop, I received a text from my mother saying I should buy face masks if I could because they were sold out all over the metro.

Fast-forward to the last quarter of the year. I have lost the little muscles I had gained from working out the past few years, the definitions unrecognizable. I tried to arrest it, the muscular atrophy, bought myself the necessary accessories. But my efforts proved futile. I long for air and space, and this house is not built for movement; the air, stopped and still, does not flow.

There is hair everywhere. I leave them and I see them, the strands, everywhere I go, as if to trace my path so as not to be lost. But the path is not worth revisiting, and there is no need to be reminded, always, of one’s cage.

All I get now from the sun are its reflected rays, from the neighbors’ roofs or cars or walls. Its heat, however, remains and permeates.

* * *

Lately, I find myself staring at my cat’s face a lot, stoic, as if in a contest of who is more a cat, the cat or the concept. I start to think that maybe we have all been in a state of atrophy since the day we were born, and it is only now, locked down, that we get to stare, cat-like, at this internal disintegration, this act of decreation.

At some point it became absurd to me — because my body is now an altogether different creature that does not encounter the same external elements it used to — to keep tending to this wilting vessel until I die, repeatedly brushing and washing and scrubbing and rinsing; like listening to the same album on repeat until my ears, then my mind, numb (hesitant to switch to a different album for fear of disturbing some psychic or mystic flow).

If only this body could turn beautiful as it atrophies, like ancient statues forgotten in the recesses of ancient cities, overgrown with leaves and moss and roots, flowers sprouting on cracks in the concrete — romantic.

Some days I swear I no longer taste anything I put in my mouth, the palate blunt. I alternate between sweet, sour, salty, savory. I indulge in an overload of carbohydrates and fats; the same dishes and snacks, again and again, cyclical. Maybe it is this cyclical desensitization, this lack of stimulation, that leads to sensual atrophy.

I think of when the technology of 3D films was introduced, how overwhelming it must have been to the senses of moviegoers. And now, here we are, desensitized by the most modern technology available to mankind.

* * *

I remember the times, before they atrophied in quarantine, when my senses would peak and overlap and synergize — synesthetic.

That time in Sagada when, instead of taking photos or videos, I recorded the hushed sound of the room. It was night and there were guests at the lobby/diner/cafe of the inn, chatting/eating/drinking, and the moment felt warm, so I recorded it, captured it with the built-in microphone of my phone. That sound, before it got lost in the degradation of my old phone, would always bring to my tongue the pure taste of the canned all-malt beer I ordered that chilly January night.

Or that time in Palawan when I also recorded the sound of the night, as the canoe slowly glided along the dark river, the audio capturing the coolness that was just starting to descend, the oddly arousing scent of the paddler—remnants of sun on his skin—and the blinking lights of the fireflies, the reason we were all on that canoe, under clear skies, that one humid night in May.

* * *

We, the so-called lucky ones, sing in chorus of mental exhaustion and emotional coagulation.

I learned that to be privileged is, in some ways, to be malcontent; to always look for ways to be discontent; to rock the boat if it becomes too still, or peel off the wallpaper as soon as the pattern gets dry.

Sometimes, I admit, I wish for misfortune; a misfortune grave enough, crippling, enough for me to break down and cease the tireless attempt to be indispensable in this world of temporary. Sometimes I wish this is the end, or the beginning of the end. Depleted, I no longer have the energy to start a new normal. I feel inside me, all the time, this refusal to engage; I cannot find the bandwidth to connect to others. I feel this strong urge to run away and leave civilization behind; and yet, there is nowhere to run to. The world is closed.

* * *

I understand I am lucky to be in a good spot when the bomb dropped and the iron curtain forced us into isolation. Still, I think I understand now why the caged bird sings; why the caged bird rages, sheds, atrophies.

I feel that my body, in a sense, has shrunk; my bones shrunk; my psyche shrunk. It has deformed itself into the shape of this house, like water, except I am afraid it will not revert to its original state. Dysmorphic, a permanent victim of this torpor that has led to stasis, to ossification.

In this room I sleep with no lights: total darkness. This way I can pretend the room is infinite and not closing in on me. For black is the color of theater, which is to say it is the color of fantasy and pretense. Black makes anything possible; it can tear down walls of a walled city.

* * *

I open the window to hear sounds, then I play music to drown out the sounds. I seek the clash, a sensation of some sort. The neighbors’ nightly spousal spats; crude exclamations and humdrum declarations from passersby; the screaming engines of vehicles reverberating through my walls, disrupting the stillness for a second or two.

I hear my walls creak as my father opens their bedroom door; the floor creaks as my mother walks down the stairs. I hear the smallest shifts in beds, because the quiet has gone complete, as the night goes deeper and I report for work. Surely they hear my sounds too? Unless I have decomposed into a ghost, translucent and mute.

Sometimes the quiet is static; it pains. Like an Akerman film where silence is sacred and the sound of a human voice is almost hostile, sacrilegious.

The conversations I partake in — the ones where words get to come out of my mouth in templates — are few and far in between, uttered as if in speech bubbles by absent, floating minds. Foreign characters and images entangle the web and saturate the screen: a cacophony.

* * *

Every month is a blink of an eye. I sleep, dreamless, then awake into a fever dream.

I have been watching old TV shows from as far back as the 1950s, catching up on culture and history, and I realized that this supposedly banal act is actually a way of folding time and consuming it — ingesting twenty, thirty years in a matter of days — and escaping the present.

Everywhere, I read how a book or a film or an album is the book or the film or the album for these times. Sometimes, I seek them to make sense; sometimes I avoid them to keep sane.

Sometimes, I sing to myself to know that time has not stopped and I have not been left behind; that despite my rejection of this timeline, I am still part of the continuum. I sing, ecstatic (from the Greek ekstasis, meaning trance or mental distraction), as the kid below the street wailed and wailed and flew into rage. (It was a chorus of different songs, but a chorus nonetheless.) I sing, the same way I sometimes make verbal notes; because even if no one else hears it, even if the sound simply ricochets off these walls and back to the ears of its speaker, the act somehow tethers me to reality.

After some time, it occurred to me that in the months I have spent within these walls, I have already created a small history, as concrete as any other, something I can refer to in present and future inner monologues: a history with a story but no plot.

* * *

I read a lot nowadays: books, lyrics, articles, subtitles. I read like my life depends on it, because, in a way, it does. My last few threads of sanity are hanging on each word I consume. I have this urge to consume things simultaneously. Trains of thought would pass my mind and I could not tell if they were something I saw in a film or heard in a song or read in a book. Information merge; words and images tessellate. I find common threads and weave them together: mental peregrinations, from a film to a song to a book.

At some point it occurred to me that we relate more to films and songs and books, not just understand the structure but capture the soul, when we ourselves are in a heightened state of the senses: confused, in love, heartbroken, euphoric. And of course we do; because those works of art, the ones worth consuming, are created by people with heightened senses. To truly understand what they are saying — for the message or the story to pierce the heart — one must rise to the state they were at during the conception of the art, which is something that cannot be forced for it happens by chance.

* * *

Others will write of this blip in history and find a way to tell the story of the times — the sick people, living in a sick economy, ruled by sick politicians. Others will produce more poignant pieces of prose and poetry. Still, in my small capacity, I write of it because all I have now is time, which is to say all I know now is time. So I try to capture it, with bare hands, like holding water as the river runs.

Months into lockdown, I started to ingest things in fragments and vignettes — deconstructed, pure and raw. There is a stream and there is, I believe, a consciousness. I turn to reading and writing in hopes of understanding, to build up the Lego parts and complete the puzzle. I read and watch and listen as if to do so is to keep hold on life itself.

I began to think that if I write down these seemingly random thoughts and note their source and trigger and who and how I was when they occurred to me, then maybe I would be able to stitch together different parts or fragments of me and end up with some sort of encyclopedia of the self.

* * *

“I am giving up personhood to become a full-time abstract concept,” I read online.

I do not know when the clock stopped at 15:59:43. Maybe it stopped while I was trying to capture the image of the bird atop the phone line before it flees, or what the light reveals before it fades, or the thought before it evaporates. (Writers are always in danger of losing the magic of the moment, tirelessly trying to capture it.) Because the keenest thoughts — the ones that produce images so sharp they could cut you — I learned, come in the in-betweens, the amids, in the thick of — not in the stillness.

The sunbeam that visits at certain times of day, percolating the power lines and windowpane, twice refracted, slicing across my bedroom wall. At night, lying on my bed with the windows open, staring at the ceiling and witnessing the interplay of lights, zoetrope-like, from cars passing the street below. Somehow I know it will all make sense, to someone someplace sometime.

_

Renzo Acosta is an editorial assistant at INQUIRER.net who “self-prescribes an overdose of movies, music and books to combat the pandemic blues.”

https://www.facebook.com/inquirerdotnet/videos/2263942083864572/

RELATED STORIES:

How ‘Philadelphia,’ landmark AIDS movie, holds up in 2020

Image: INQUIRER.net/Marie Faro

For more news about the novel coronavirus click here.

What you need to know about Coronavirus.

For more information on COVID-19, call the DOH Hotline: (02) 86517800 local 1149/1150.

The Inquirer Foundation supports our healthcare frontliners and is still accepting cash donations to be deposited at Banco de Oro (BDO) current account #007960018860 or donate through PayMaya using this link.