Under siege

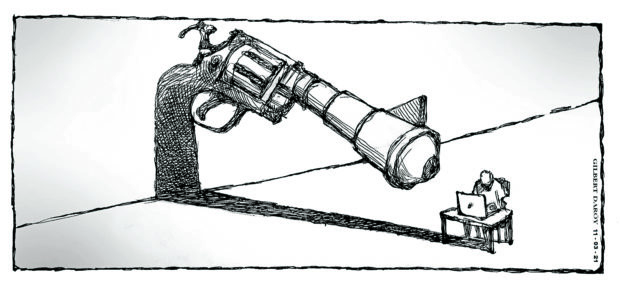

Radio anchor and former Inquirer correspondent Orlando “Dondon” Dinoy was inside a makeshift broadcast booth in his rented apartment in Bansalan town, Davao del Sur last Oct. 30 when an assailant barged in and fatally shot him six times at close range.

Dinoy, a reporter for Davao City-based online media outlet Newsline Philippines and blocktime anchor of Energy FM in Digos City, became the 21st journalist killed under the Duterte administration, according to the National Union of Journalists of the Philippines.

Article continues after this advertisementIt was a “barbaric killing,” bewailed the Kapisanan ng mga Brodkaster ng Pilipinas (KBP)—“an attack and an affront to the lives of journalists and the freedom of expression guaranteed in the Philippine Constitution.” The KBP demanded a “speedy and fast” police investigation to bring the perpetrators to justice.

Even such anguished denunciations have somehow become rote these days as the deaths continue to pile up from the unabated assassinations of not only journalists but also lawyers, activists, environment workers, drug suspects, and ordinary citizens.

The top brass of the Philippine National Police was as usual quick with assurances that the brutal slay would not go unpunished. PNP chief Gen. Guillermo Eleazar said violence against media was “unacceptable” in a democracy, and that the police would coordinate with the Presidential Task Force on Media Security — a body created under the Duterte administration as a result of numerous media killings — to solve Dinoy’s cold-blooded murder.

Article continues after this advertisementDetained Sen. Leila de Lima gave voice to a common thought in her reaction to the pro forma police statements: “Another member of the media brutally slain. Another call for a prompt and impartial investigation. Another prayer, hoping that it will be the last of the killings. But it will never stop as long as impunity remains to be a state policy.”

Indeed, despite the repeated claims by the Duterte administration that press freedom is alive and well in the Philippines and denials that journalists are in any danger, the Philippines has been ranked the 7th deadliest country in the world for journalists in the annual Global Impunity Index 2021 issued by the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ). The ranking is a slight improvement—the Philippines went down from fifth place in 2019. But the country remains among the most perilous countries for journalism at this time, where “conflict, political instability, and weak judicial mechanisms perpetuate a cycle of violence against journalists,” said CPJ deputy editorial director Jennifer Durham.

It is not just journalists who feel the climate of fear under the Duterte administration. Ordinary Filipinos do, too.

According to the September survey of the Social Weather Stations (SWS), 45 percent of Filipinos, or about one of two adult citizens, believe “it is dangerous to print or broadcast anything critical of the administration, even if it is the truth.” That undercurrent of fear has been a constant presence: A November 2020 SWS survey released in March this year found an even higher number—65 percent of Filipinos—who believed it was risky to say anything against the government.

That sentiment was likely concretized by the biggest attack on the press that had happened earlier in 2020: Congress’ denial of the franchise of media network ABS-CBN Broadcasting Corp., which had been the target of repeated threats of closure by President Duterte (“If you are expecting na ma-renew ’yan [franchise], I am sorry. I will see to it that you are out,” he said in December 2019).

The dangerous environment for Filipino media was highlighted by the Norwegian Nobel Committee when it awarded the 2021 Nobel Peace Prize to Rappler head Maria Ressa and Russian journalist Dmitry Muratov for “their courageous fight for freedom of expression in the Philippines and Russia.” In the wake of that unprecedented honor given a Filipino, Malacañang cobbled together a statement of congratulations after three days, but insisted on its own reading of the international rebuke: It was a “not a slap (on the government) because as everyone knows, no one has ever been censored in the Philippines,” said presidential spokesperson Harry Roque.

Reminded of the shuttering of ABS-CBN under the administration, Roque claimed his principal had nothing to do with it: “You cannot blame Congress for not renewing the franchise of ABS-CBN because that is one of their powers. That is not an order emanating from the executive nor it is a matter within the jurisdiction of the executive.”

Furthering his Orwellian take on the Nobel Prize given to Ressa, Roque said it was in fact proof that “press freedom is alive” in the country.

Is it? Dinoy’s killing, so close to the Nov. 2 commemoration of the International Day to End Impunity for Crimes Against Journalists, grimly belies that oblivious narrative, offering yet another bloodstained reminder that the press in these parts continues to be under siege.