Divorce and death

At the second presidential debate sanctioned by the Commission on Elections and held in Cebu on Sunday, the candidates were asked to answer three questions without explanation, simply by raising their hands if they were in favor and keeping still if they were against. It was a made-for-TV format, but the exercise proved to be a welcome respite from the often heated exchanges that characterized the debate.

At the second presidential debate sanctioned by the Commission on Elections and held in Cebu on Sunday, the candidates were asked to answer three questions without explanation, simply by raising their hands if they were in favor and keeping still if they were against. It was a made-for-TV format, but the exercise proved to be a welcome respite from the often heated exchanges that characterized the debate.

The up-or-down format used by TV5 was also a helpful guide to the candidates’ views on long-simmering, much-discussed issues.

On the question of allowing divorce in the Philippines, none of the four candidates—Vice President Jejomar Binay, Davao City Mayor Rodrigo Duterte, Sen. Grace Poe, and former interior secretary Mar Roxas—raised their hands.

To those who have only intermittently followed the so-called Duterte-serye, the melodramatic twists and turns of the Davao mayor’s unlikely run for the presidency, the unanimous opposition to allowing divorce in the Philippines must have come as a surprise. After all, isn’t Duterte known for his romantic entanglements, cheerfully admitted both in private and in public?

But earlier this month, in another forum, Duterte already took an unequivocal stand against divorce. “In legal separation, there’s still hope for the husband and wife to come together, but not in divorce,” he had said. “You don’t have to love your wife to live together.” He added: “I’m not in favor of divorce for the sake of the children, and abortion, for me, is a no-no.”

A series of Social Weather Stations surveys has found increasing public support for the legalization of divorce in the Philippines, the only country outside of the Holy See where divorce remains banned in the statute books. From 43-44 percent in May 2005, support rose to 50 percent in March 2011 and to 60 percent in December 2014.

The other candidates had also made earlier statements recording their opposition to divorce. Last January, for instance, Roxas made it clear: “I’m one of the 40 percent na hindi payag (who oppose it),” he told GMA News.

This common position may be based on deeply held personal values, or part of a deliberate strategy not to attract opposition from influential religious institutions, but it is interesting to see the candidates take what is now a minority position.

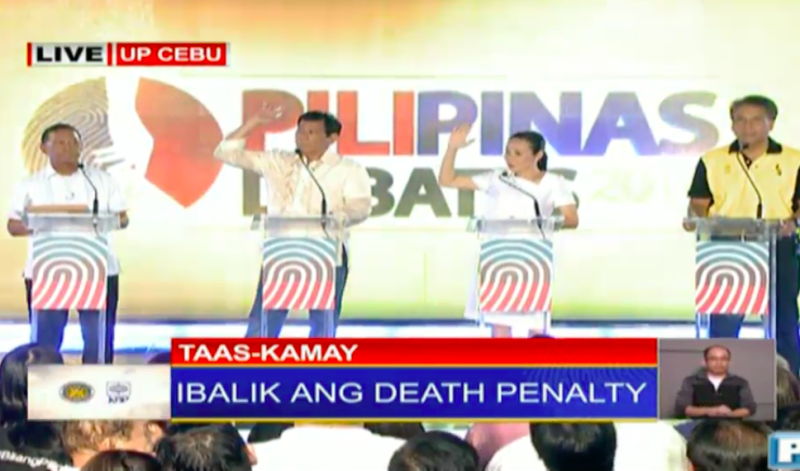

On the question of reimposing the death penalty, archrivals Binay and Roxas found common ground in saying no. But Duterte and Poe both raised their hands, with Poe rushing to add “only for heinous crimes.”

Since its founding, the Inquirer has opposed the death penalty because of both principle and the penalty’s practical consequences. The principle can best be explained using Duterte’s own words about divorce. “In legal separation, there’s still hope for the husband and wife to come together, but not in divorce.” If the modern purpose of incarceration is not revenge but rehabilitation, then capital punishment is a disavowal of that purpose. In jail, there’s still hope even for the worst offender, but there’s no going back from the lethal injection chamber.

The most powerful argument against the death penalty, however, remains its skewed nature. Capital punishment mostly claims the poor and the ignorant, those who do not have the resources to hire adequate legal representation. Perhaps not coincidentally, this is exactly the same charge leveled at the victims of the so-called Davao Death Squad (a point raised by Roxas in the debate): Almost all of them were poor, and if they were criminals, they were engaged in petty crime—not, say, billion-peso scams that defraud thousands.

Both Binay and Roxas have previously taken anticapital punishment positions. In the first presidential debate held in Cagayan de Oro, Binay said he did not believe in the death penalty and said taking someone’s life was “trabaho ng Diyos ’yan”—literally, God’s work. Roxas based his opposition on procedural justice: “You may have a death penalty law but if you can’t catch criminals and even if you arrest them, you fail to present proofs because of a lousy investigation, then that’s useless.”

Poe’s position was surprising, given that only last November she said she was against it. But whether based on deeply held personal values or political considerations, it is interesting to note that the two candidates with the biggest public support (in an admittedly very tight race) support a policy that, in practice, is antipoor.

RELATED VIDEO