Language(s) my mother gave me

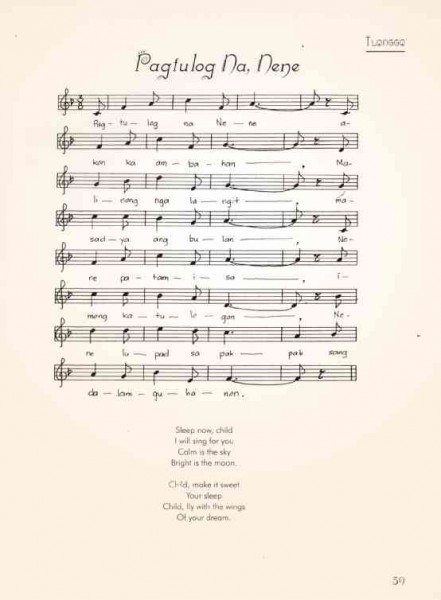

TWO of the illustrations by Joanne de Leon in the book “Antukin: Philippine Folk Songs and Lullabyes.” The songs were selected by Felicidad A. Prudente, Ph.D.

(Historical Note: On Feb. 21, 1952, police opened fire on demonstrating students of Dhaka University in the defunct East Pakistan. They were fighting for recognition of their Bangla language as an official language of the newly created Pakistan state. At least seven students died and were immediately hailed as the country’s language martyrs. The language struggle was followed by a war of national liberation that gave birth to a separate Bangladeshi state.

(Historical Note: On Feb. 21, 1952, police opened fire on demonstrating students of Dhaka University in the defunct East Pakistan. They were fighting for recognition of their Bangla language as an official language of the newly created Pakistan state. At least seven students died and were immediately hailed as the country’s language martyrs. The language struggle was followed by a war of national liberation that gave birth to a separate Bangladeshi state.

In 1999, Unesco proclaimed Feb. 21 International Mother Language Day. This year’s theme is: “Quality education, language(s) in education and learning outcomes,” which is discussed in this piece.)

“A closed bottle filled with water was left in the freezer overnight. In the morning, the glass was found broken. Why did freezing cause the bottle to break?”

This was one of the test items in Grade 4 science during the 2003 Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS). Students who scored well in this item came from the Russian Federation (39 percent), Australia (29 percent) and Japan (27 percent). The international average stood at 19 percent. The Philippines was, on this item, the worst performer at 1 percent.

One compelling finding in the TIMSS tests was about language. Students who spoke the language of test at home scored higher than those who didn’t. In 1999 and 2003, the Philippines ranked first among participants in using a language of test (English) that was not its own. As expected, it came close to last among nations in academic standing in science and mathematics.

DepEd Order 74, K-12

Consequently, the Arroyo administration took the first bold step in 2009 to reform our language-in-education policy. The Department of Education (DepEd) issued Department Order No. 74, which introduced mother tongue-based multilingual education or MTB-MLE.

To ensure continuity of this policy, the Aquino administration convinced Congress to enact the Kindergarten Act in 2012, and the “K-12” law and the Early Years Act in 2013. These laws contained landmark provisions, which state that basic education shall be delivered in languages understood by learners.

These laws made the learner’s first language (L1) the primary language of instruction (LOI) of reading materials and of assessment in elementary education. L2s (English and Filipino) can be taught as separate subjects and become the primary LOI only sometime in high school.

‘Additive’ vs ‘subtractive’

While it is way too early to assess the effectiveness of our multilingual education policy, there are indications that we are straying away from the correct path in our theory and practice of MTB-MLE.

The most fundamental idea to remember is that MTB-MLE is an L1-based additive program in which L2 adds to the learner’s L1. It is not an L1 to L2 system in which L2 replaces or subtracts the L1 from the learner’s repertoire. But no less than the DepEd is perpetuating this fallacy of subtractive education. Department Order No. 31, series of 2013, requires L1 to be the LOI in Grades 1-3, with Filipino or English taking over as the medium thereafter.

Contrary to common sense

Not only is this interpretation patently unlawful but it is also contrary to common sense. Why use L1 in the first place only to discard it after Grade 3?

Another poorly understood idea about MTB-MLE is the distinction between the L1 used at home and in the streets for conversational purposes and the L1 used in school settings for academic purposes.

An L1 that a learner brings to school may be sufficient for the early grades where concrete things in face-to-face situations are talked about. But for the upper school levels where cognitively challenging content and abstract thought become the norm, L1 conversational skills must evolve into cognitive academic language proficiency (CALP).

Students can optimally develop their L1 CALP when L1 academic use is allowed at least up to the end of elementary grades. Meanwhile, teaching L2s as separate subjects prepares learners to receive instruction in both L1 and L2 later in school. Even after this happens, learners should continue to master content through their L1, and not exclusively in their L2s.

Bridging L1 and L2 does not mean developing CALP through L1 in the lower grades and through the L2s in the upper grades. Otherwise, MTB-MLE would just be another subterfuge to marginalize the learner’s L1 and overvalue English.

Building an L1 academic register for each subject and for every grade level is a worthy objective for both teachers and students. Long-term L1 practice will afford the teachers and their students the opportunity to experiment on how to express complicated concepts in science, math and chemistry through the language they are most comfortable with.

Debates between “purist” and code-switching approaches cannot be avoided and will necessarily ensue. But best practices will give birth to a robust academic language complete with the appropriate terminology and vocabulary. When academic language is supported by an interactive teaching style that facilitates discovery learning across all curricular subjects, the chances of students’ success in school are increased significantly.

Education research

In earlier articles, I invoked the findings of international studies, especially in Africa, which show why “early-exit” programs fail.

One, it takes at least 12 years for children to learn their L1. Two, older children (10-12 years old), not younger children, are better L2 learners. Three, it takes 6-8 years of strong L2 teaching before L2 can successfully work as LOI. And four, untimely L2 use can lead to low scores in literacy, science and math.

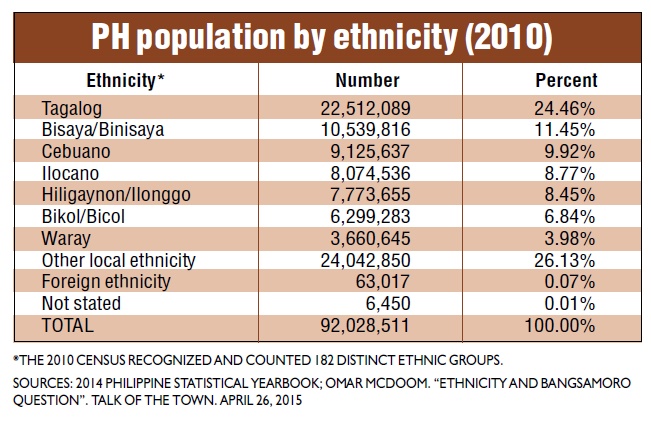

Local research also does not support DepEd’s “early-exit” scheme. Studies were conducted in 2013, 2014 and 2015 by the US Agency for International Development and RTI International to establish a national baseline of reading performance for Filipino early graders. The 2013 study covered the English and Filipino languages in third grade while the 2014 and 2015 assessment dealt with four L1s (Ilocano, Sugbuanon-Binisaya, Hiligaynon and Maguindanaon) in Grades 1 and 2.

The 2013 results showed that Filipino and English reading performances were nearly equivalent (close to 70 percent) in terms of fluency, decoding and accuracy of reading words in isolation. Comprehension scores, however, differed widely. Eighty percent of comprehension queries (attempted) were answered correctly by 67 percent of children reading in Filipino, compared with only 18 percent of children reading in English.

The 2014 study revealed similar findings. Grades 1 and 2 children were tested in oral reading (40 to 60 words long) and on how well they understood a written text. Up to 38 percent of children in some L1s could not read a single word of text at the end of Grade 2. Disappointingly, the average comprehension rate in Grade 2 was close to, or below, 50 percent in all languages.

Slow progress

The 2015 “follow-on” report was more diplomatic in its executive summary: “Overall, the 2015 survey shows that for the most part, slow progress is being made, both in implementing MTB-MLE and in improving student performance in their mother tongues.

“Much progress is still needed. Teachers must have and use MTB-MLE materials, and they must use classroom time more productively by focusing more on the instructional practices that engage students in reading and reading-related exercises.

Many, including me, have expressed reservations about the competencies that the reading instruments are supposed to measure. But the data, nonetheless, raise serious doubts on how prepared Filipino Grade 3 students are in “reading to learn” in Grade 4 and beyond.

Simply put, three years may be too short for learners to master the academic language in their L1s. An abrupt transition to L2 instruction will only exacerbate an already untenable situation.

The most urgent task at present is a shift in learning paradigm from a “short-exit” mindset to an honest-to-goodness additive one. This means developing and using L1 CALP throughout the elementary grades and for as long as possible. Strong teaching of L2s as subjects should accompany L1 CALP development. In time, L2 CALP slowly progresses and joins L1 CALP as language of instruction.

There is no place in MTB-MLE for the “short-exit” or even the “late-exit” scheme. Under a genuine MTB-MLE program, L1 is used for life-long learning and is never exited from the learner’s linguistic repertoire.

Overhaul curricula

A clearer and more precise elaboration of additive MTB-MLE will pave the way for the overhaul of current basic and higher education curricula for students as well as the reconceptualization and restructuring of preservice education in the country. Teacher competence-based standards will have to be revised.

Since space constraints will not allow a more detailed explanation here of such radical restructuring, the following words of Filipino national artist Rolando Tinio will have to suffice: “There was no such thing as English for science, or English for mathematicians, or English for art—until English scientists did science in English, English mathematicians did mathematics in English, English artists did art in English, and so on.

“In short, they created, actually created, the various nuances of the English language which we propose to enjoy effortlessly. In the last analysis, to be a professional means also to create the language of one’s profession. Because Filipino professionals experience their professions in a borrowed language, they have never been called upon to discharge this part of their obligation. We are, in the worst sense, mere ‘users’ of English; we have no part at all in the creative process.”

Monolingual baggage

The long-term challenge for MTB-MLE success is the intellectualization of Philippine languages across the curriculum through prolonged usage. But before we can do this, we should rid ourselves once and for all of the monolingual baggage (e.g. “English only”) that has weighed this nation down for the past 100 years.

These findings add to our existing knowledge of an educational system that is one of the most studied in the world. They prophesy a tortuous road ahead for Philippine MTB-MLE if we continue to refuse to confront the harsh realities staring us in the face. It is a road that we would have doubtlessly conquered a long time ago had we heeded the research findings.

(Ricardo Ma. Duran Nolasco, Ph.D., is an associate professor in linguistics in UP Diliman. He can be reached at rnolascoupdiliman@gmail.com.)