Macoyismo: The myth of a ‘golden age’

Nostalgia can be an intoxicating balm, if not a weapon. As in individuals, nations tend to look back to the “good old days,” often more in the realm of myth than history, to regain strength and inspiration in times of trouble and insecurity,

Reeling from a “Century of Humiliation” at the hands of Western powers and imperial Japan, early-20th century Chinese nationalists leaned on the glories of the Ming, Tang, and Han dynasties to retain self-dignity and rekindle their hope in a better future.

But Chinese cartographers were apparently too intoxicated with patriotic fervor to bother with the actual maritime boundaries of ancient Chinese kingdoms, thus their modern “nine-dash-line” concoction, which has fueled all sorts of contemporary shenanigans across much of the South China Sea.

From Russians and Turks to Greeks and Persians, a whole generation of nationalists similarly found inspiration in their imperial pasts to overcome present humiliations. In short, nostalgia for a “golden age” feeds a profound psychological need among human beings, if not inspire whole nations, in moments of collective distress and despondency.

Bereft of either an imperial past or the splendor of ancient monarchies, the Philippines has often struggled to locate its own version of the “good old days.” For some, our best days were in the precolonial era, where gender parity, rustic solidarity, and organic egalitarianism were said to have reigned supreme. For others, we should take great pride in the age of the Filipino “ilustrado,” when Manila was the “pearl of the Orient” and our universities produced Jose Rizal’s generation of thinkers who inspired revolutionary upheavals across the colonial world.

But for a growing number of Filipinos, Ferdinand Marcos Sr. is the embodiment of a golden age of national prosperity. Throughout their long reign, the Marcoses effectively presented themselves as a modern-day “Maharlika” of indigenous royalty and aristocratic splendor, thus their persistent popularity to this day.

At its very core, what I call “Macoyismo,” the underlying ideology of Marcos’ rule, was based less on a coherent vision of national development and more on a fantastical project that drew on powerful imagery, performative initiatives, and, above all, nostalgic mystique.

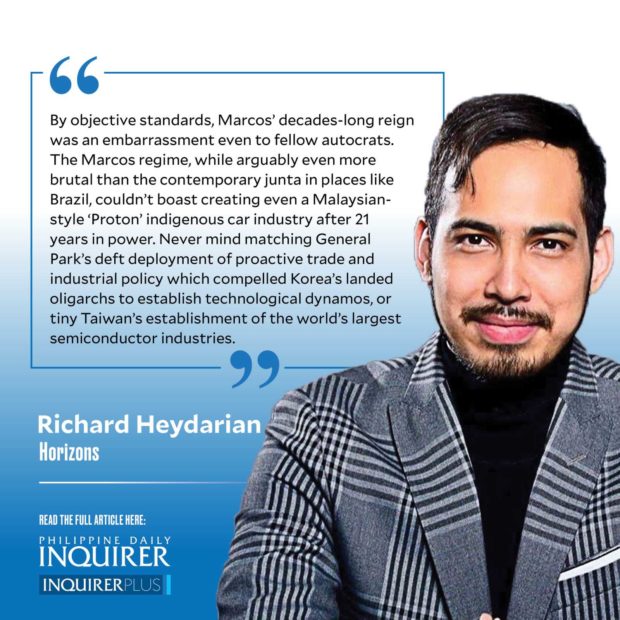

By objective standards, Marcos’ decades-long reign was an embarrassment even to fellow autocrats. Contemporary dictators in South Korea and Taiwan, namely Park Chung-hee and Chiang Kai-shek’s heirs, competently oversaw developmental states that established the foundations of the world’s leading conglomerates, from Samsung and Hyundai to the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company.

In nearby Malaysia and Singapore, authoritarian leaders such as Mahathir Mohamad and Lee Kuan Yew also oversaw the transformation of imperial backwaters into newly industrialized nations with state-of-the-art public infrastructure.

The Marcos regime, on the other hand, while arguably even more brutal than the contemporary junta in places like Brazil, couldn’t boast creating even a Malaysian-style “Proton” indigenous car industry after 21 years in power. Never mind matching General Park’s deft deployment of proactive trade and industrial policy that compelled Korea’s landed oligarchs to establish technological dynamos, or tiny Taiwan’s establishment of the world’s largest semiconductor industries.

Presiding over one of Asia’s fastest growing economies, President Diosdado Macapagal, aided by his capable Ilocano technocrat Cornelio Balmaceda, oversaw Manila’s selection as the host of the Asian Development Bank (ADB) in the early 1960s. By the time Marcos stepped down from power in the mid-1980s, the Philippines was economically bankrupt, a laggard in Southeast Asia. Saddled by crushing debt and deeply corroded state institutions, thanks partly to Marcos’ avaricious cronies, the country has seen successive Filipino presidents struggle to change the Philippines’ developmental course in the past three decades. More than a dozen coups, a legacy of the Marcos-era politicization of the armed forces, didn’t help either.

The Filipino presidents who partly succeeded, namely Fidel Ramos and Benigno Aquino III, were soon supplanted by populist successors who had little appreciation for the sweet science of modern governance.

As I argued in a previous column (“Why the Marcos brand remains popular,” 10/26/2021), both our educational and judicial institutions have also enabled a Marcosian revival by largely skipping questions of accountability and justice.

But in our era of unregulated social media and systematic impunity, who cares about objective facts anymore? The Marcoses have been the masters of nostalgic politics with few precedents in history. This is their ultimate formula for success.