Data anarchy

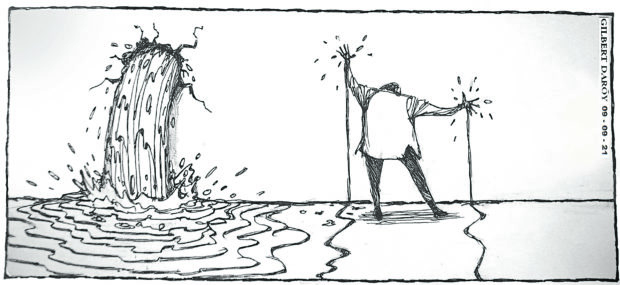

A day after the government made the surprise announcement that Metro Manila — the epicenter of the still-raging COVID-19 pandemic — would revert to looser quarantine protocols and shift to “granular” instead of sweeping lockdowns from Sept. 8 to 30, it suddenly backtracked and decided to retain the modified enhanced community quarantine (MECQ) status until Sept. 15.

Palace spokesperson Harry Roque did not elaborate on the reasons behind the about-face, other than to say that the Inter-Agency Task Force for the Management of Emerging Infectious Disease on COVID-19 had “deferred the pilot implementation” of the general community quarantine with Alert Level System in the National Capital Region. Thus, MECQ will stay at least until Sept. 15 or until a new system is implemented, “whichever comes first.”

The most likely reason is that the government actually does not have a clue how to put the localized lockdown system into effect. Consider: The granular lockdown scheme was supposed to help contain the spread of COVID-19 while reopening more parts of the battered economy, but hours before the shift was to begin, the guidelines had yet to be finalized. If one thought that was a terrible demonstration of basic management, there was more, as Interior Undersecretary Epimaco Densing comically proved when he declared that the alert levels under the new system would now consist of “bawal, bawal nang konti, at pwede.”

Once again, shambolic, haphazard, and last-minute decision-making — the by-now familiar pattern of the Duterte administration’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The regular exhalations emanating from Malacañang appear to be guided more by bluster and political expediency than by hard science, thus straining the health system to the breaking point and scarring the economy to an extent not seen by the country since the war.

Before the granular mess, there was the administration’s decision to lift the travel ban on 10 countries, including India and Indonesia, which had seen record-breaking outbreaks of the hyper-contagious Delta variant. This, just as the Philippines had itself passed the bleak milestone of 2 million confirmed cases and seen the daily case rates hitting their highest since the pandemic began.

Some 18 months after COVID-19 struck in March 2020, the Department of Health (DOH) is still unable to process crucial data fast enough, leading to disturbing gaps in the COVID-19 numbers. The danger is obvious: Shoddy data could present an inaccurate view of the severity of the pandemic situation and lead to misplaced, unsound policies.

Health advocate Dr. Gene Nisperos of the Community Medicine Development Foundation was among those who expressed concern about the yawning gaps in the official data, such as when laboratory numbers on Aug. 31 showed that 17,612 were positive but the DOH reported only 13,821. This could be the reason “we are losing the pandemic fight. We’ve fallen behind the enemy,” warned Nisperos.

Questioned about the numbers, Health Undersecretary Maria Rosario Vergeire admitted to a “disconnect” between government data on hospital bed occupancy and the reality on the ground. How did it happen? Incredibly, all this time, the DOH had not been counting the number of suspect and probable COVID-19 cases being hospitalized.

If there is one area where the need to collect and rely on accurate, comprehensive, and timely data to guide policy decisions is paramount, it would be contact tracing. For the move to granular lockdowns, for instance, World Health Organization Philippine representative Dr. Rabindra Abeyasinghe stressed that the “critically important element” for the shift to succeed is the availability of “very accurate data.” And to secure that data, “good, strong” contact tracing is a must, as it will determine where the transmission of COVID-19 is actually happening. Otherwise, the wrong areas will be freed up or locked down and the virus will continue to spread because of failure to break the chain of transmission.

Contact tracing, however, has been one of the “weakest points” of the country’s COVID-19 response, Abeyasinghe said.

And there is no sign it will improve, as the government-backed StaySafe app has proven to be a massive dud. The app that was supposed to augment contact tracing efforts has had “almost no impact” on efforts to locate those exposed to COVID-19 positive people, Health Secretary Francisco Duque III himself said.

With no significant moves to step up contact tracing and with the DOH unable to quickly clear its backlog and clear up its numbers, the planned shift to granular lockdowns is bound to have the same results. The data anarchy underpinning the administration’s correspondingly chaotic pandemic response guarantees that the virus will remain uncontained, and the country will continue to languish under the perpetual threat of lockdown.