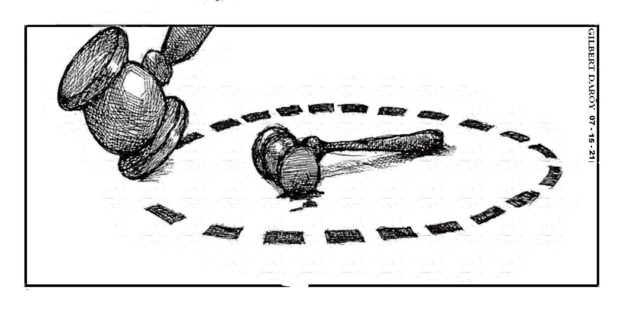

Deterring excessive force

Lawyers, activists, and human rights advocates scored a major victory last week when, in a move toward greater accountability and transparency in law-enforcement operations, the Supreme Court put an end to the cross-border issuance of “wholesale” search and arrest warrants by the courts, and required the Philippine National Police and other law enforcers to use body-worn cameras when serving these judicial orders.

In Administrative Matter No. 21-06-08-SC made public last week, the high tribunal ruled that the special power of local court judges of Quezon City and Manila to issue search warrants beyond their judicial regions will no longer be allowed. This means that their issued warrants can only be served within the National Capital Region, revoking a 2004 resolution that authorized the executive judges of the Manila and Quezon City Regional Trial Courts to act on applications filed by agencies such as the PNP and the National Bureau of Investigation for search warrants involving crimes such as illegal possession of firearms and ammunition, even if these will be served outside their jurisdiction.

The Supreme Court was pushed to clip the powers of the Quezon City and Manila executive judges to issue these cross-border warrants following accusations by human rights groups that these orders had become virtual “death warrants” for members of red-tagged human rights organizations.

During the “Bloody Sunday” incident last March 7, for example, nine activists died and six were arrested in simultaneous pre-dawn raids in Calabarzon conducted by the PNP and the military, who were executing search warrants issued by Manila judges. Forensic evidence recently showed that these nine activists accused of being NPA rebels were “really shot to be killed,” as forensic pathologist Dr. Raquel Fortun put it, negating claims by authorities that they had died because they resisted arrest and fought the authorities serving the warrants.

Quezon City Executive Judge Cecilyn Burgos Villavert, meanwhile, issued the search warrant that led to the Human Rights Day raid in 2020, resulting in the arrest of the “Human Rights 7” group of activists. That warrant was eventually nullified for lack of probable cause. Villavert also issued a search warrant in October 2019 that was served in Bacolod City at the offices of progressive groups such as Bayan Muna, resulting in the roundup of 57 people, including 10 minors, who were allegedly participating in firearms and explosives training. This search order was likewise quashed.

These incidents prompted some 139 lawyers, including former vice president Jejomar Binay and former senators Rene Saguisag and Wigberto Tañada, to call on the Supreme Court to “take immediate, concrete, and responsible action” against the widespread killings and arrests of activists in the implementation of search warrants issued by Metro Manila judges.

In a rare statement in March following the Bloody Sunday incident, the Supreme Court denounced the killings and said it would promulgate rules on the use of body cameras during the service of search and arrest warrants. The release of such guidelines is thus a welcome development, and should be welcomed primarily by the police force as sparing them the risk of unwarranted allegations.

Under the new rules contained in the 17-page ruling, failure by law enforcers to use the required body camera or at least one alternative recording device when serving warrants will render the evidence “inadmissible for the prosecution of the offense for which the warrant was applied.”

The new rules on the use of body-worn cameras were rendered “to support law enforcement and to guarantee the protection of fundamental rights,” said the Supreme Court. These recordings, it stressed, “can deter the excessive use of force by law enforcement officers in the execution of warrants and can aid trial courts in resolving issues that may become relevant in the criminal case, such as conflicting eyewitness accounts.”

The National Union of Peoples’ Lawyers (NUPL), which had pleaded for the high court to act on the questionable issuance of these warrants, said it was “grateful and appreciative of the responsive action of the Supreme Court on the matter.”

NUPL president Edre Olalia, however, warned of loopholes in the guidelines that can still be exploited or used to circumvent the rules. These include the limited number of mandatory recording devices to be used and who among the team should wear the devices, and also the consideration that may be extended to police claims that the device failed to record during the raid.

Nevertheless, Olalia cheered these “welcome reforms” and looked forward to the rules being tested on the ground, to ensure that the justice system will use the warrants as intended—to root out criminal elements, and not to expediently target those who come into the government’s crosshairs.