Endangered ‘pawikan’ still at high risk

FEMALE green turtle returns to sea after laying eggs on one of the beaches of the Turtle Islands. PHOTO BY A.G. SAÑO

Smuggling of Philippine wildlife has been in the news in Sabah. Twelve Filipinos were detained last month in Sandakan, Sabah, for trying to bring in 19,000 eggs of pawikan (marine turtles).

Romeo Trono, former head of the Pawikan Conservation Project of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR), says this is “probably the biggest haul of marine turtle eggs being transported by Filipinos and confiscated by the Sabah Marine Police during a single operation over the last 30 years.”

Article continues after this advertisementThat’s about the length of time Trono, also a former country director of both the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF)-Philippines and Conservation International-Philippines, has spent working on marine turtle conservation issues in the country and in Southeast Asia.

Turtle islands

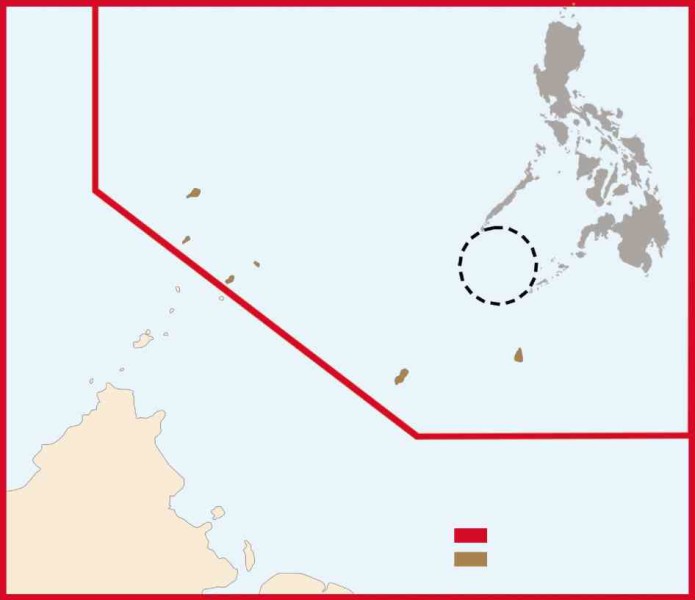

The market value of the 19,000 eggs is estimated at 30,000 Malaysian ringgit or P350,000. It is most likely that the eggs are from green turtles (Chelonia mydas), among the commonly encountered marine turtles in the Philippines, which frequent a group of nine islands in the southernmost part of the country right on the border with Sabah, called the Turtle Islands.

Article continues after this advertisementThe Turtle Islands is special, as it is one of only 10 major rookeries used by green turtles in the world and the only one for the Asean region. Eighty percent of all green turtle nestings in the Philippines happen here as well. It is closer to Sabah than to any other island in the Philippines and that is why trading with this neighbor is most lucrative. All these transactions, illegal or legal, involve the movement of people and trade of marine resources.

“In 2011, we observed as many as 120 nesting green turtles laying eggs on just one island in the Turtle Islands, Baguan, every night, from only 80 in 1982,” Trono said. “If turtle scientists are right, this is about the time when the hatchlings we released during the 1980s should be returning to their natal beaches to lay their first clutches of eggs.”

Drop in egg production

Baguan Island, along with the other islands in the group, could easily have supplied the number of smuggled turtle eggs that day, the equivalent of about 190 nests. The Philippine Turtle Islands produced 1.44 million eggs in 2011, which DENR reported early this year to have dropped to around 1 million.

Marine turtles are successful evolutionary animals, having survived several extinction episodes on the planet. They have been around since the time of the dinosaurs, predating modern humans by about 109.8 million years.

So successful is their adaptation that they have become abundant in tropical and temperate waters across the globe. All our islands with beaches are potential nesting sites for these animals, but the effects of human activities on the environment are taking a toll on their populations.

Egg production of green turtles in different parts of Southeast Asia has decreased by 65 to 90 percent between 1930 and 1993. The region, in fact, is considered the world’s greatest consumer of turtle eggs, according to a WWF-Philippines report. Aside from the eggs, the meat is eaten and the beautiful protective shell used for decorations and trinkets.

BAGUAN Island provides one of the more productive nesting beaches in the Turtle Islands, collectively producing around one million eggs a year. PHOTO BY CALOY LIBOSADA

Victims

Marine turtles are also victims of by-catch, destruction of their habitats (beach development, sea reclamation and degradation of feeding areas, such as reefs and sea grass beds), and ingestion of plastic trash and various marine debris. It is estimated that over half of marine turtles have eaten plastic, which could potentially kill them.

Of the five species of marine turtles in the Philippines, four are considered endangered and one—the hawksbill (Eretmochelys imbricata)—is critically endangered.

Only 1 percent of turtle eggs laid survive—around 0.2 percent as estimated by scientists, if human impact is factored in, according to the Marine Wildlife Watch of the Philippines.

This means that, with the recent arrest and the destruction of the eggs, 19 potential turtles have been killed—off-nesters that should be coming back in 35 to 50 years, when they reach reproductive age, to lay up to 1,000 eggs per season.

This is why every egg is important—a single egg lost is a great loss to the population. It should be emphasized that such smuggling happens on a daily basis in the Turtle Islands, whether the perpetrators are caught or not.

The life of a marine turtle spans more than a hundred years. So when making a conservation plan, we need to think long-term. The problem is not to be addressed only by one community and one administration, but requires sustained efforts through several administrations and generations.

Coastal reclamation

For example, coastal reclamation affects the new recruits of turtles born there 50 years ago, who, for the first time, are coming in to lay their first clutch, only to find that the beach they were born in is no longer there.

The successes of previous conservation efforts have been described by the chair of the International Union for Conservation Marine Turtle Specialist Group, Dr. Nicholas Pilcher, as “a stunning example of important beaches being protected by governments with the support of research and conservation agencies.” He said the “numbers of turtles are growing, the populations are stable and that’s the sort of thing we would like to see happen.”

Efforts not enough

However, it seems that with the continuing harvest and smuggling of eggs, even after the declaration of the area as a sanctuary in 1982, the Turtle Islands’ establishment as a National Integrated Protected Area System site in 1999 and the passing of the Philippine Wildlife Act in 2001, these efforts have not been enough to stop the trade.

International trade is strictly prohibited for any marine turtle and its by-products, including their eggs, as they have been listed under Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) since 1981. The Philippines and Malaysia are signatories to this agreement.

Heritage protected area

Our six islands, together with Sabah’s three others, comprise the Turtle Islands Heritage Protected Area (Tihpa), established in 1996 and recognized as the first transboundary protected area for green turtles in the world. Tihpa was envisioned as a model transborder conservation area.

Smuggling marine turtle eggs across the border is also a crime committed against the Sabah Wildlife Conservation Enactment of 1997, which does not allow the possession, consumption and trade of marine turtle eggs, and is in violation of both the Philippine Wildlife Act and CITES.

There is no strict monitoring of marine turtle egg harvests in the Turtle Islands and the rest of the country. It’s as if it is not happening. The sad part is, even conservation areas allow exploitation to happen.

The same weekend as the smuggling incident, 30 marine turtle eggs sold in Baliwasan, Zamboanga City, were confiscated by the DENR Region 9 office and the Philippine National Police-Regional Maritime Unit 9. The raid came after a photo tip that was uploaded on Facebook, which was reported to the DENR-Biodiversity Management Bureau.

“It seems the Turtle Islands is now becoming a stunning example of failure due to DENR’s unresponsiveness to the problem of unregulated turtle-egg poaching and daily smuggling, which they have obviously known about for decades,” says Trono.

The problem persists because of the lack of effective law enforcement in the Philippines. There is also the lack of political will among the authorities and lack of awareness among the populace.

All these continue to contribute to the decline of marine turtle populations, even if they have been declared protected in the country for over 40 years now. If we want to comply with the international trade agreement, we need to look into preventing Filipinos from supplying foreign traders and markets.

More creative solutions

Aside from better enforcement, we need to find more creative solutions to address this problem, which will involve reducing poverty and eradicating corruption in the country.

Filipinos must take pride in having these creatures thrive in our waters. Appreciation of our natural resources, especially the uniqueness and abundance of Philippine biodiversity, is crucial in conservation efforts.

SMUGGLED marine turtle eggs, 19,000 in total, from the Philippines, confiscated by Sabah Marine Police in Sandakan on July 16. PHOTO BY SABAH MARINE POLICE

Turtle tourism

There is money to be made for communities in turtle tourism. Among other marine wildlife attractions the Philippines could offer, swimming with marine turtles is now becoming popular, such as what has been happening in Apo Island in Negros, Pandan in Mindoro, Balicasag Island in Bohol and Moalboal in Cebu.

“It is such a waste to use these animals once, just when we could benefit from them in a sustainable manner and without having to kill or sacrifice a turtle, or even an egg,” ” says Caloy Libosada, president of Responsible Tourism Philippines.

Ecological value

Marine turtles have intrinsic ecological value as well, and should not be seen as just commodities. They are valuable in maintaining the health of our coastal ecosystems, providing services such as enriching beach nutrients with their eggs, grazing in sea grass to make them better nurseries for fish, controlling jellyfish populations, and controlling algae and sponge growth on reefs, allowing more corals to grow.

We need marine turtles to thrive to ensure that our oceans are healthy, so that we, too, could thrive.

In the meantime, the four skippers, aged 21 to 49, and eight passengers, seven men and a woman, aged between 17 and 63, who were caught with the smuggled marine turtle eggs, will have to face charges. They can be fined 50,000 Malaysian ringgit or about P570,000, or jailed for five years, or both, for having violated Sabah laws.

Mundita Lim, director of the Biodiversity Management Bureau, says: “As an immediate action, we are working with partners, the local government units and also with the Malaysian government to investigate those behind the large-scale poaching of turtle eggs, so we can have them prosecuted and penalized to send a strong message that we will not tolerate any form of illegal trade of wildlife.”

The widespread illegal wildlife trade is one of the biggest threats to biodiversity in the world and one of the major illegal industries, comparable to the traffic of drugs and weapons and is worth about

$19 billion annually.

(AA Yaptinchay, DVM, MSc is the director and founder of Marine Wildlife Watch of the Philippines (MWWP), a nonprofit, nonstock conservation Philippine-based organization promoting a better appreciation of the marine environment, its ecological processes and how it affects us all in the local context mainly through social media. He can be reached through the MWWP Facebook page.)