Will real Jose Rizal please stand up?

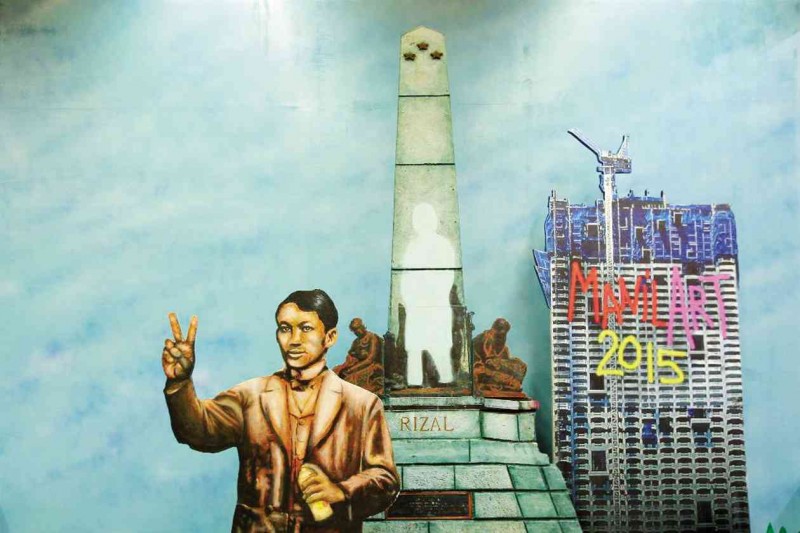

THE HERO AND THE CONDO Jose Rizal steps down from his monument at Luneta Park in Manila in Bonifacio Juan’s installation at ManilArt 2015. ManilArt organizers invited fairgoers to have their photos taken with Rizal as spoiler, much like the Torre de Manila condominium building in the background. MANILA.COCONUTS.COM

There are three kinds of nationalists. For want of a better term, I shall classify them as A, B or C.

The A nationalists can tell gold (freedom or human rights) from the gold-plated trinket (political independence). They buy the gold because they know the intricacies of the market well enough to profit and not lose from their investment.

Article continues after this advertisementThe B nationalists, on the other hand, cannot tell one from the other. Neither do they have the panache of a seasoned trader. So, they get easily conned to invest in trinkets whose glitter feeds their illusion that they have a treasure in their hands.

Pseudos

The C nationalists are not nationalists at all. Pseudos, they prey on the B nationalists’ penchant for glitter and build their fortune selling them their trinkets, which they claim cost them their lives mining, smelting and designing.

Article continues after this advertisementThe B nationalists glorify these quacks as heroes for such sacrifice and look askance at the A nationalists whose keen eyes they do not have and whose safe way of acquiring their gold through reputable shops is, to them, cowardly, not heroic.

Reformers

These buyers of trinkets, the B nationalists, snigger at the class A nationalists—the “mere reformers” and men of peace like Jose Rizal whose revolution is not a violent, bloody one; whose weapon is the pen and not the sword; whose battlefield is the psyche of both tyrant and slave; whose ideology is liberty, not political independence.

Jose Rizal has been extolled these past many years, not as a reformer and man of peace but as the opposite—a man “generally acknowledged as the inspiration, if not instigator of national independence and unity”—in order to redeem him in the eyes of the B and C nationalists in our country. But historical data and the words of Rizal himself say the opposite.

Noli’s purpose

The purpose of “Noli Me Tangere,” wrote Rizal to his critic, [Vicente] Barrantes, was not to incite a revolution, but to effect the Filipinos’ mental and moral evolution:

“Yes, I have depicted the social sores of ‘my homeland’; in it are ‘pessimism and darkness’ and it is because I see much infamy in my country; there the wretched equal in number the imbeciles. I confess that I found a keen delight in bringing out so much shame and blushes, but in doing the painting with the blood of my heart, I wanted to correct them and save the others.” (Reply to Barrantes’ criticism of the Noli, Feb. 15, 1890, La Solidaridad).

Noli’s sequel, “El Filibusterismo,” wrote Rizal, is a study of subversion, to make his readers see “the structure of its skeleton,” not an enticement for it: “If the sight should lead our country and its government to reflexion, (Note: not subversion!) we shall be happy no matter how our boldness may be censured …” (Dedication page, “El Filibusterismo,” Europe, 1891).

In Rizal’s essay, “The Philippines, a Century Hence,” and in a proclamation Rizal addressed to “Our Dear Mother Country Spain,” Rizal said: “I have also believed that, if Spain systematically denied democratic rights to the Philippines, there would be insurrections and so I have said in my writings, deploring any such eventuality, but not hoping for it.”—(“Memorandum for My Defense,” Dec. 12, 1896)

Aversion to revolution

Rizal’s aversion to revolutions was patently consistent from the beginning of his writing career. In an article he contributed to La Solidaridad, “The Truth for All,” May 31, 1889, years before he was accused as the instigator of the Katipunan, he warned the Spanish government in the Philippines:

“If you continue the system of banishments, imprisonments and sudden assaults for nothing, if you will punish the people for your own faults, you will make them desperate, you take away from them the horror of revolutions and disturbances, you harden them and excite them to fight.”

He used the word, “horror.” This says the opposite of what our B and C nationalists insist! They also insist that the formation of La Liga Filipina was one of the charges against him.

Union, development

To this charge, Rizal had countered brilliantly and truthfully:

“Let them show the statutes of the Liga and it will be seen that what I was pursuing were union, commercial and industrial development and the like. That these things—union and money—after years could prepare for a revolution, I don’t have to deny; but they could also prevent all revolutions because people who live comfortably and have money do not go for adventures.” —(“Data for my Defense,” Dec. 12, 1896, Fort Santiago)

According to Leon Ma. Guerrero, the reason [Eulogio] Despujol had exiled Rizal was because of the antipapal pamphlets found in the luggage of his sister, who arrived with him from Hong Kong, and not because he suspected him of planning to lead a revolution.

Guerrero based his statement on what Rizal had written down in his diary:

“After we had conversed a while he (Despujol) told me that I had brought some proclamations in my baggage; I denied it. He asked me to whom the pillows and sleeping mat might belong and I said, ‘they were my sister’s.”—(Diary entry, July 6, 1892)

According to some extant letters unearthed, his exile was the opportunity that Marcelo del Pilar, a B nationalist, seized upon to organize a separatist club. With Rizal out in Mindanao, he (Del Pilar) can now push for independence through armed revolution—an issue that Rizal had blocked at every opportunity while they were together in Europe.

Del Pilar told his brother-in-law, Deodato Arellano, to organize the Katipunan in preparation for an armed revolution for independence.

Valenzuela’s accounts

Pio Valenzuela’s four different accounts of his meeting with Rizal have turned Rizal into a weakling, flip-flopping from an A to a B then to a C nationalist. But Valenzuela’s first account of his meeting with Rizal in Dapitan is more credible because it is consistent with Rizal’s writings as early as 1884.

Guerrero tells us in his book, “The First Filipino,” that:

“Bonifacio had at first been reluctant to believe Valenzuela’s report of Rizal’s attitude. (No, no, no! A thousand times no!) but, once convinced of its truth, he ‘began to insult Rizal, calling him a coward and other offensive names.’ Bonifacio, for his own reasons, had forbidden Valenzuela to reveal Rizal’s disapproval of the revolution, but he had done so anyway and many of those who had offered contributions had backed out.”

‘Accomplice’

The revised versions of Valenzuela’s conversation with Rizal as recorded in his (Valenzuela’s) memoirs, which are more compatible with B and C nationalists’ purpose, are so at variance with Rizal’s sentiments about revolutions that they are absolutely comical.

Manuel F. Almario calls Rizal an accomplice of the insurgents because he writes, “Rizal never betrayed his knowledge of the plot to the authorities …” when in fact, it is on record that Rizal did.

This, Rizal states unequivocally:

“When later, despite my counsels, the uprising broke out, I offered spontaneously, not only my services, but also my life, and even my name so that they might use them in the way they deem opportune in order to quench the rebellion; for, convinced of the evils that it might bring, I considered myself happy if with any sacrifice, I could forestall so many needless misfortunes. This is also on record.” —(“Manifesto to Some Filipinos,” Dec. 15, 1896)

Katipunan

In this manifesto, Rizal denounced the Katipunan in very strong terms, calling it absurd, fatal, savage, criminal and a dishonor to Filipinos, and asked the rebels to go home. He was not trying to save his neck nor his family “from further persecution,” as alleged by Almario, because Rizal’s manifesto wasn’t the first article he wrote against armed revolutions for independence.

As early as 1884 and up till a few hours before his execution, he had been denouncing armed revolutions and independence, while preaching about the Philippines’ future assimilation with Spain.

Mob

Finally, Rizal’s “Mi Ultimo Adios” describes the rebels as an unthinking, delirious mob, who know not the consequences of their action, too easily seduced by the C nationalists’ favorite slogan

—“for country and home,” a slogan used by terrorists all over the world until now. He is willing to die, if his death will stop the carnage and his beloved country will live and find redemption (not independence) at last.

His death indeed stopped the carnage, albeit for a while, because demoralized by his unjust and cruel death, and tempted by the cash reward offered, the rebels sold the Katipunan to the authorities barely a year later (Dec. 15, 1897), at the Pact of Biak na Bato. But his country only got political independence 50 years later from another foreign power and not yet the redemption (the people’s mental and moral evolution) he had tried so hard to bring about.

Third World

One of the major reasons for the Philippines becoming a Third World nation after the United States granted her political independence is this: No other class A nationalist openly took Rizal’s place after his death.

Our historians and scholars who handled the lessons of our past were and are B and C nationalists. They extol and continue to extol the trinket called political independence while condemning Rizal’s smarter choice for a still weak people—gold nuggets of civil liberties via assimilation into a First World nation—by denying that he ever chose this for us.

Being what they are, B and C nationalists, they couldn’t see or they deny what they see

—the danger of the trinket they preferred. In the hands of the weak and wicked, this independence becomes a threat to civil liberty (remember martial law?) and progress (look at our unemployed, our homeless, our millions of overseas Filipino workers, our garbage, etc.) as it has indeed become in the Philippines.

I have yet to meet someone from among our historians and scholars who is focused on bringing about our redemption by examining possible technologies that may effect our moral evolution.

If our B and C nationalists do not morph into class A nationalists soon, we will forever be producing student activists, like the 43,000 cadres of the ’70s who took up arms against the Marcos’ administration and died accomplishing nothing. The evil they blamed on Marcos persists up to this day long after he and his administration have gone.

Just like how Bonifacio’s Katipuneros and Aguinaldo’s guerrillas accomplished nothing, too, not even winning the independence they pretended to pursue. This is the truth in our history.

The independence granted us by the Americans was not due to any “heroic” efforts of our B and C nationalists but to the Americans’ shrewd realization that they can colonize us more efficiently if we had an independent democratic government.

America’s ‘chosen’

Through our elections, the Americans can put their “chosen” in top positions and get everything they want, without compromising their noble statutes’ stand against acts of subjugation. Those chosen, who don’t do as they are told, are assassinated (Magsaysay) or ignominiously removed (Marcos, Erap and Gloria) by an adverse press their ambassadors foist on the people who have been molded to be B and C nationalists by our historians.

We need class A nationalists to give us, in the words of Alejandro Roces, a “factual and objective perspective—one that strives for meaningful interpretation of people and events of the dim past,” not a warped, subjective appraisal of these to support one’s inferior and dangerous ideology.

Until these class A nationalists come forward, Rizal will remain, long after the sesquicentennial of his birth, the dreamer of unfulfilled dreams of peace and progress (the fruits of redemption) in his beloved Philippines.

(Margarita Ventenilla-Hamada is the founder and directress of two nontraditional schools, Harvent School in Dagupan City and in Lingayen, Pangasinan. She is the author of two books on Rizal, “Swatting the Spanish Flies” and “Transcending Rizal” as well as books on education and quantum physics, and skillbooks on the three basic academic skills.)