Never again: A nation of ‘5th graders’

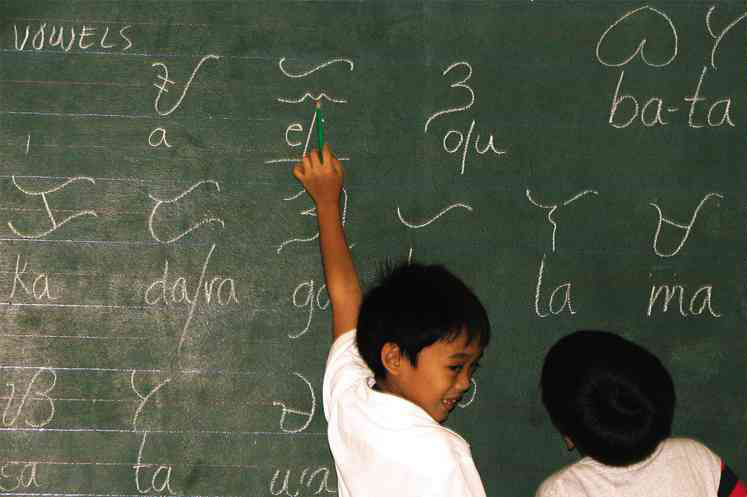

‘ALIBATA’ Writing “alibata” or “baybayin” (a prehispanic script) amuses two Grade 1 students at St. John’s School in Malaybalay City during its Arts Week that promotes indigenous culture. GRACE CANTAL-ALBASIN/INQUIRER MINDANAO

1 What is the current state of Philippine education?

“A nation of ‘fifth graders,’” the late Dr. Josefina R. Cortes, former dean of University of the East College of Education, said of our country that has long suffered from poor learning outcomes. Evidence of this is aplenty:

In 2013, around 7 million Filipinos did not know how to count and 17 million had poor comprehension skills.

In 2014, the general scholastic ability of our high school students was a dismal 44.48 percent.

Filipino students fared poorly in the 1999, 2003 and 2008 Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) tests.

TIMSS strongly hinted then that it was time to reform many of our education practices, including the language of learning.

2 What is mother tongue-based multilingual education (MTB-MLE) or first language (L1)-based MLE?

MTB-MLE is the country’s new language-in-education policy. For learners, this means learning to speak, listen, read, write and think in the first language or L1 (Binisaya, Tagalog, Ilocano and Waray, etc.).

It also means studying math, science, history and social studies in the language, lived experience and sociocultural realities they grew up with.

3 When will learning in Filipino and English start?

As they develop a strong foundation in their L1, children are gradually introduced to their second language(s) or L2 (Filipino and English). When L1 and L2 instruction is adequate, cognitive skills and subject content acquired in L1 can be transferred to L2.

In the process, learners can use both languages for higher education. Contrary to earlier formulations, MTB-MLE is an L1 and L2 additive system, not an L1 to L2 subtractive system.

4 Does MTB-MLE mean changing the medium of instruction (MOI) and translating materials into L1?

MTB-MLE involves: (a) well-trained teachers in the subject’s content, in the required languages and in instructional methods; (b) cognitively demanding L1 and L2 curricula; (c) original, error-free and culturally relevant readings; and (d) an empowered community.

In the 2012 and 2013 proficiency tests, our elementary teachers scored 49 percent and 54 percent in English, respectively, and 46 percent and 49 percent in Math-Science, respectively. MTB-MLE won’t work by simply changing the MOI or translating existing materials.

5 What kind of learners does MTB-MLE want?

Multiliterate. They can read and write competently in L1, Filipino and English.

Multilingual. They can use these languages in various situations.

Multicultural. They can live and work harmoniously with people of cultural backgrounds different from their own.

6 Why use L1 in school?

One’s own language enables a child to express himself or herself easily, as there is no fear of making mistakes. Through this language, children can immediately articulate their thoughts and add new concepts to what they already know.

Because they can now express themselves, their teachers can more accurately assess what has been learned and where they need help. L1-speaking parents can now participate more actively in educating their children.

7 But our children already know their language.

What they know is L1, which is used for daily interaction. Success in school depends on the academic and intellectualized language needed to discuss more abstract concepts. This takes four to seven years or longer for children and teachers to acquire.

8 Why use the national language or Filipino in school?

The Philippines is a multilingual and multicultural nation. A national language is a powerful resource for interethnic dialogue, political unity and national identity. That language is Filipino, which is predominantly Tagalog but spoken nonetheless throughout the country as an L2.

9 Why use English in school?

Languages of wider communication like English should be part of the multilingual curriculum of a country. Most world knowledge is accessible in English and, therefore, knowledge of English is certainly useful. It is not true, however, that students will not learn science and mathematics if they do not know English.

The educator Paulo Freire has cautioned teachers “never to allow the students’ voice to be silenced by a distorted legitimation of the standard language.”

10 Has MTB-MLE been legislated in the Philippines?

Yes. In 2012 and 2013, Congress passed the Kindergarten Act, the K-12 law and the Early Years Act. These laws contain language provisions which state that:

Basic education shall be delivered in languages understood by the learners.

L1 shall be the primary MOI in early years, kindergarten and elementary education.

The shift from L1 to L2 as primary MOI should be gradual and should be completed in high school.

Schools can indigenize and localize the curriculum based on their sociocultural contexts.

The production of local teaching materials will be devolved from the central authorities to the regional and division units.

11 Is L1 use up to Grade 3 only?

No. The law provides for the gradual shift from L1 to L2 as primary (not exclusive) MOI beginning in Grades 4 to 6. The transition is expected to be completed sometime in high school when learners are competent enough to receive L2 instruction.

This means that L1 should remain the primary MOI up to the elementary grades. Once L2 takes over as the primary MOI in high school, L1 becomes an auxiliary MOI. The law authorizes the Department of Education (DepEd) to lay down the conditions under which L2 becomes the primary MOI.

12 What does studies show on early exit programs?

Early exit programs (where L1 is used up to Grade 3 only) are weak programs because:

Children need at least 12 years to learn their L1.

Older children (10 to 12 years old) are better L2 learners than younger children.

It also takes six to eight years of strong L2 teaching before L2 can successfully be used as MOI.

Premature L2 use can lead to low achievement in literacy, science and math.

13 Will L1 and L2 use facilitatelearning?

Yes. Many studies indicate that students first taught to read in their L1, and then later in an L2, outperform those taught to read exclusively in an L2, as shown in the Lubuagan Kalinga MTB-MLE program. Here L1 experimental classes scored nearly 80 percent compared with just over the 50 percent scores by L2 control classes in Grades 1, 2 and 3 tests.

14 Will increasing the time for English or making it the exclusive MOI improve our English?

Large-scale research in the past 30 years has provided compelling evidence that the critical variable in L2 development in children is not the amount of exposure but the timing and manner of exposure.

The 11-year Thomas and Collier’s US study showed that nonnative English learners who were schooled under an all-English curriculum scored lowest (between the 11th and 22nd percentile ranks) in national tests. English learners, who were given L1 support for six years, scored the highest (between the 53rd and 70th percentile ranks), which were well above the norm for their English-speaking peers.

15 What is the best way to attain English proficiency?

For nonnative speakers of English, like us, the best way is to teach it well as an L2. This depends on the proficiency of teachers, the availability of adequate models of the language in the learner’s social environment and opportunities to use the language outside the classroom setting.

Andy Kirkpatrick of Griffith University argues that becoming bilingual in the national language and a local language will provide L2 learners with a positive concept in their own identity before they come to learn English.

16 Don’t we need English for the country’s economic development?

Yes, but English is not enough. Steve Walter of Summer Institute of Linguistics has shown convincingly that countries whose populations have access to L1 education are the most developed. Those countries whose people are denied L1 education are the least developed. Worse, a mismatch exists between the needs of industry and our educational system.

The consensus among employers is that our high school graduates are weak in their ability to communicate, to think logically and to solve problems, making it hard to employ them.

17 Will the use of local and regional languages be detrimental to building one nation?

No. On the contrary, it is the suppression of local languages that may lead to violent conflicts, disunity and dissension. This is what happened to the former East Pakistan whose rulers wanted Urdu to be the sole and exclusive official language. As a result, the people of East Pakistan who spoke Bangla rebelled and formed a separate Bangladeshi state.

18 Does MTB-MLE violate the national language provision of the 1987 Constitution?

No. The Constitution empowers Congress to regulate the use of Filipino as the official medium of governance and of education. What Congress wisely did was to divide the instructional space among L1, English and Filipino pursuant to the early years act and the new K-12 law.

19 Can local languages be used as MOI?

The late national artist Rolando Tinio once spoke of a basic fear among us that our languages are undeveloped for use for higher learning. He reminded us that the advanced state of the English language was reached through the efforts of its users.

We can intellectualize our languages only by continuously using and cultivating them to produce new knowledge and original research in the basic, intermediate and higher learning domains.

20 Is it costly to practice MTB-MLE?

An L2-based education produces more dropouts, repeaters and failures than the L1 and L2 systems. This wastage makes L2-based systems costlier than the L1 and L2 systems.

21 What about classrooms with several L1s?

One option is to use the area’s lingua franca spoken in the children’s multiethnic surroundings. The downside here lies in the possible impairment of learning for those unfamiliar with the lingua franca.

A more challenging solution is to use two or three L1s in a “mixed” classroom. Melting pot areas usually have gifted teachers who are fluent in two or three languages. Diglot (with two L1s) and triglot (with three L1s) learning materials can be produced for this type of classroom.

Diverse learners are exposed to multiple L1s and negotiate meanings as they interact with each other, thereby producing multicultural subjects. Many educators frown upon organizing classrooms on the basis of language because of the segregationist, discriminatory and exclusivist mind-set that this practice may engender.

22 Does MTB-MLE also apply to tertiary education?

Yes. A language policy for tertiary education must uphold the principle that instruction should be delivered in a language or languages understood by the learners. The pervasive sociolinguistic diversity in the country and our colonial history add to the difficulty in choosing the appropriate language of instruction.

An option may be to use L1 or Filipino for some subjects, English for others, and even mixed varieties for the rest provided real learning takes place and the course objectives are met. But in no case should L1 or Filipino be discarded at the tertiary level, especially in the general education curriculum.

23 What is the state of MTB-MLE in the country today?

Problems are piling up as evidenced by:

English is still the MOI in many public and private elementary schools.

L1 will be used only up to Grade 3 and the L2s will take over as MOI in Grade 4.

Unexplainably, only 19 Philippine languages can be used as MOI. The DepEd curriculum is still congested and biased for the dominant L2s.

Teachers are being trained haphazardly or not being trained at all, especially in subject content.

L1 and L2 materials are merely translated, of inferior quality and hastily produced.

Despite numerous lapses in MTB-MLE implementation, teachers and officials are creatively finding ways to make the plan work. “Big” books, “small” books, manipulatives (learning tools), posters, vocabularies and “lesson study groups” —all in the local languages—are being produced at a furious pace at the school level.

Tertiary education institutions are reviewing and revising their curricula for teachers in accordance with the country’s new policy on L1 and L2 education.

All these form part of the apoy sa ilalim and apoy sa ibabaw solutions that will help this country leapfrog from being a nation of fifth graders to a country of achievers and high-skilled professionals in the foreseeable future.

(Ricardo Ma. Duran Nolasco, PhD., is a faculty member of the Department of Linguistics of the University of the Philippines in Diliman, Quezon City.)