Interpreting Marcos’ ‘chief technocrat’

WHEN Gerardo P. Sicat’s “Cesar Virata: Life and Times Through Four Decades of Philippine Economic History” (University of the Philippines [UP] Press) came out in August, I knew it would present an interpretation of Virata’s role during the martial law years different from what I have already read.

Since 2005, I was aware that Sicat was writing Virata’s life history. Sicat himself told me so when I requested to interview him for a “Living History Series” project on the martial law technocracy of the UP Third World Studies Center (TWSC) of which I was then the director. As is well known, Sicat served the Marcos regime as chair of the National Economic Council in 1970 and director general of the National Economic and Development Authority (Neda) [1973-1981].

Sicat at that time replied that he was busy with his Virata book and could not grant an interview but told me to try contacting him again in the near future.

Oral history project

I had another chance later, in 2007, as a member of the three-year research project (2007-2010) on “Economic Policymaking and the Philippine Development Experience, 1960-1985: An Oral History Project,”1 which was cocoordinated by Professors Yutaka Katayama of Kobe University and Cayetano Paderanga Jr. of UP Diliman. Sicat again declined to be interviewed, saying that he was still busy writing his Virata book.

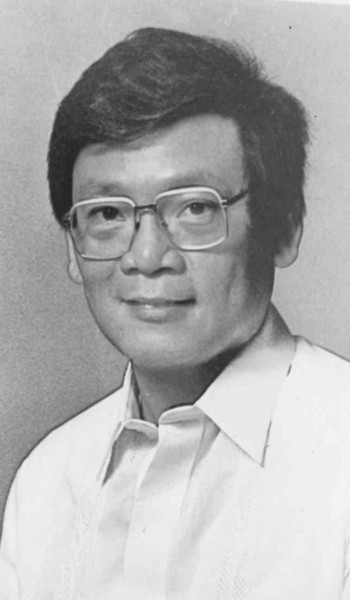

Unlike Sicat, Virata readily agreed to be interviewed—a total of 13 intensive sessions lasting 52 hours. The large number of Virata interviews was understandable given the length of time he served under Marcos starting in 1967 as deputy director general for investments of the Presidential Economic Staff, secretary of finance (1971-1986) and concurrent prime minister (1981-1986).

Holding these crucial positions earned Virata the moniker Marcos’ “chief technocrat.” Virata apparently found our interviews worthwhile and pertinent, so he gave copies of the transcripts to Sicat which the latter acknowledged in his book to be very valuable. Sicat wrote that “it provided a second source of additional oral history materials aside from my one-on-one interviews with the subject” (p. 787).

Technocracy’s rise

I published a series of journal articles on martial law technocrats based on the interviews we conducted with them.2 The main difference between my accounts and Sicat’s was his omission of the political and the socioeconomic context in which Virata is situated. As in our interviews, Sicat started off his book with Virata’s family and educational background, particularly his life in UP, his entry into the business community and, ultimately, as a technocrat in government.

This part of our interviews made me reflect on how Virata emerged as part of the power elite in a society ruled by influential and contentious political families/dynasties. Sicat provided a lot of details of this, particularly, names of persons not identified in our interviews, but he did not provide the context in which to understand the emergence of a “Virata.”

For me, the main context has to do with the manner in which the country’s American colonial past has shaped the politics and the economy of the country. This was pursued further under the post-colonial state particularly during the Cold War era in the 1950s and 1960s whereby the United States needed to prop up Southeast Asian states as a “bulwark against communism.”

Compatible with US interests

One way of achieving this was through an economic development model guided by professionals with the “technical expertise” and the development vision compatible with American economic interests.

As noted in his coedited book “After the Crisis: Hegemony, Technocracy and Governance in Southeast Asia,” Japanese historian Takashi Shiraishi said: “American intellectual hegemony was built into the economic policy-making structure of its Asian allies through a technocracy,” with emphasis on liberalization, i.e., incentives for foreign capital.

Tripartite merger

The “technical expertise,” gained through their acquisition of US graduate degrees, made technocrats like Virata a prize catch for the Philippine business elite who were either expanding into the manufacturing sector and/or were involved in joint ventures with or servicing the needs of American multinational corporations in the country.

It was also this ideological tripartite merger of the United States, the technocrats and the state, as represented by Marcos, which assured the technocrats’ ascension into the power elite during the martial law period.

Martial law context

The other omission concerned the martial law period. As pointed out by Manila Times columnist Rigoberto D. Tiglao in his review of Sicat’s book (Nov. 11), nowhere did the author mention the atrocities of the Marcos era, especially gross human rights violations as exemplified in the incarceration, disappearances and killings of dissidents.

I agree with Tiglao that a more complete exposition of Virata’s persona has to contextualize him within this political milieu.

In the interviews, we asked Virata what he thought of the growth of the communist insurgency during martial law. His response was it had nothing to do with poverty and socioeconomic inequalities but was merely instigated from the outside.

Does this paint him therefore as the ultimate “apolitical” technocrat or was he just plain clueless about the political situation or worse, an uncaring public official?

Virata pointed out that Marcos limited the technocrats’ involvement in government to the economic sphere. Washing his hands of Marcos’ perfidies, he explained: “As secretary of finance, I was not involved in the martial law administration. It was Secretary of National Defense Juan Ponce Enrile and the Office of the President who had a direct hand in implementing martial rule” (June 6, 2008).

Even in his political position as prime minister, Virata noted he was only the head of Cabinet but he did not have control over its members and thus no authority to reverse decisions (May 28, 2008).

Ideological context

As to economic policies, Sicat painted a glowing picture of the alleged reforms instituted by Virata—something which was irreconcilable with the more credible and critical assessments of the martial law era, which depicted a bleak picture of the country’s rapid economic deterioration as the region’s basket case under the auspices of the Marcos technocrats.

In my writings, I found it crucial to highlight how Virata viewed the economic situation vis-à-vis how others perceived it. These were opposed to each other. For me, this leads us to better comprehend Virata’s character in a society where the state of the economy was highly contested between the haves and the have-nots, or the powerful and the powerless.

Even before I read Sicat’s book, I already knew that we would be offering divergent interpretations about the same person not because he is an economist and I am a political scientist. It is mainly because we are coming from two different ideological poles in viewing the country’s political economy, which I believe was shaped by the roles we played during martial law.

That is, he as key economic player in Marcos’ authoritarian regime and I as part of the antidictatorship movement. Moreover, he is orthodox in his views, conforming to a framework of mainstream economics, while I take on a heterodox perspective.

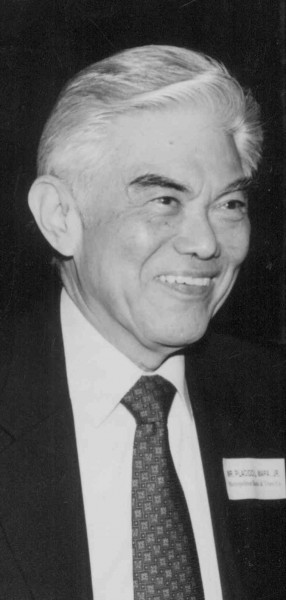

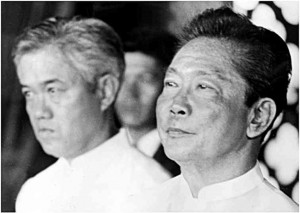

VIRATA and Sicat at the launching of the latter’s book “Cesar Virata Life and Times: Through Four Decades of Philippine Economic History”

Virata or Sicat talking

Tiglao (2014) also pointed out that there were no footnotes or in-text citations in the Sicat book. This critique made sense as the book’s narrative did not make it clear which were Virata’s views and which were Sicat’s.

Regarding the imposition of martial law, for example, Sicat wrote: “Economic reforms suddenly became possible under martial law. The powerful opponents of reform were silenced….” (p. 260). For Sicat, therefore, martial law was a necessity. When our project team, however, asked Virata whether there was a need for martial law, his reply was “nobody among us (referring to his fellow technocrats) wanted martial law.”

Relationship with elites

For Virata, martial law was just all about power and that Marcos just wanted to extend his term (Dec. 13, 2007). He added that “…when the Interim Batasang Pambansa was in session after 1978, I really wanted martial law to be lifted.” When we pointed out that he would again would have had to deal with the oligarchs in Congress, his reply was, “…well we should accept that.” (Dec. 13, 2007).

But then Virata, by his own account, had a good working relationship with the elites in the premartial law Congress, an insight which seemed to have eluded Sicat’s attention. For example, Chapter 6 highlighted the role of former

Sen. Jose W. Diokno in the adoption of the Investment

Incentives Act of 1967.

Sicat depicted Diokno as an uncompromising nationalist who favored domestic industries (p. 156) and against whom Virata and the other technocrats were helpless.

In our interviews, however, this was not the picture I got. Virata, instead, narrated how he developed a good relationship with Diokno. He shared Diokno’s view that the Philippine economic and financial situation went up and down because the original approach to business development was import substitution.

The good relations between the technocrats and Diokno were also highlighted in our interviews with Placido Mapa Jr., who headed Neda, Philippine National Bank and Development Bank of the Philippines under Marcos.

Diokno’s brilliance

Mapa narrated how he and Virata worked closely with Diokno in drafting the Investment Incentives Act and the creation of the Board of Industries. He remarked that he was impressed by Diokno’s “dedication and brilliance” in brokering the passage of a law acceptable to all parties (March 13, 2009).

It was with Sicat that Virata had differences. Concerning the Investments Incentives Act, Virata told Sicat that the latter’s recommendations concerning the rapid liberalization of the economy would never be accepted by the local industries and the politicians, thus requiring the installation of graduated tariff duties. This was based on the concept of measured capacity for industry in order to avoid overinvestment and waste of scarce capital resources.

Virata admitted that this went against free market principles but this was the government’s as well as the business community’s way of dissuading influential families from investing in the same enterprise. On this, he disagreed with Sicat, whom he described as a hard-core advocate of liberalization (Nov. 21, 2007).

Paterno

His differing perspective with Sicat was shared by another Marcos technocrat, Vicente Paterno, who revealed in our interview with him (Aug. 15, 2008) that he and Sicat were “not attuned to each other,” as he was for guided industrial development while Sicat was for the rule of market forces.

Interestingly, both Virata (Sept. 20, 2008) and Paterno traced their differences with Sicat to the latter’s being a “pure economist,” while they both have engineering backgrounds.

Virata ‘unplugged’

These differing “interpretations” of Virata may be further elucidated and clarified when the UP TWSC website uploads in 2015 the raw transcripts of our interviews with him and the other Marcos technocrats. This will be Virata speaking about himself and for himself. Given the pivotal as well as controversial role he played during the era of the dictatorship, the last word, I can imagine, will not be his.

1This research project was funded by the Japan Society for the Promotions of Science and aimed to document firsthand the dynamics of the decision-making process during this period of our history, focusing on key policy issues and the role of key decision-makers.

2Aside from Virata, among the key economic policymakers interviewed were Placido Mapa Jr., Vicente Paterno, Armand Fabella, Manuel Alba and Jaime Laya. Like Sicat, Roberto Ongpin did not accept our request to be interviewed.

(Teresa S. Encarnacion Tadem, Ph.D., is a professor at the Department of Political Science, College of Social Sciences and Philosophy, University of the Philippines Diliman. E-mail: teresatadem@gmail.

com.)