Speculation pushing prices up

(Editor’s Note: From just P20 to P25, the retail price of four bulbs of garlic at a “talipapa” [small market] in Muntinlupa City rose recently to P40. In Calumpit, Bulacan, the price of garlic jumped from only P40 a kilo to P280 last month, according to a local vendor. The sharp rise in garlic prices is felt nationwide as supply is not enough to meet demand.

The Department of Agriculture attributes the spike in garlic prices to speculation and not to a shortage in supply. It has deployed rolling stores to various public markets in Metro Manila to help stabilize prices and supply. An industry group blames import liberalization for the crisis.)

If there’s a search for a national spice, garlic can vie for it. Its pungent smell flavors Filipino comfort dishes from adobo to paksiw to fried rice. Rummage through the luggage of a US-bound balikbayan and chances are there’s a pillow-size bawang-based finger food tucked in it.

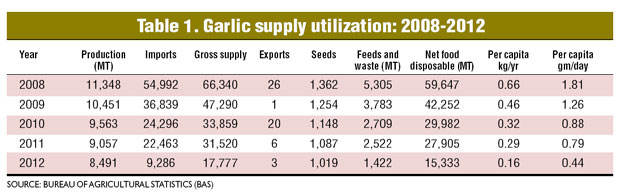

On the average, a Filipino consumes 1.43 kilos of garlic a year. So even if its price settles at P200 per kilo, the daily expense for this indispensable seasoning is 54 centavos—half the cost of sending a text message.

On a monthly basis, the country’s garlic consumption is about 11,700 tons. This year’s local production is forecast at 10,000 tons. Thus, a year’s production barely meets a month’s demand.

Ramp up production

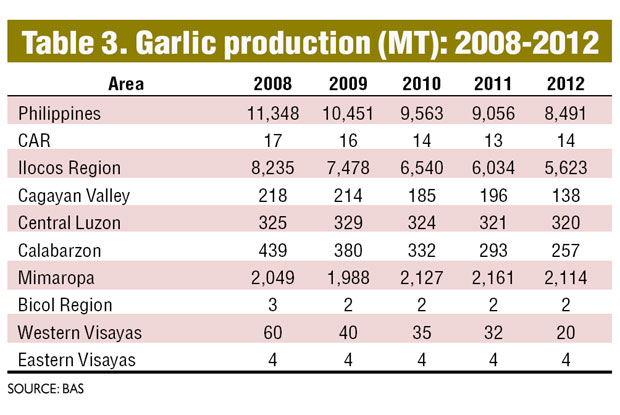

Through a package of incentives, we are ramping up production, more so after last year’s domestic output dipped to 8,848 tons after a series of typhoons drenched a crop that is averse to water.

Among our initiatives is to encourage Mindanao farmers, especially in the Cotabato area—where the soil and climate, being outside the typhoon alleyway, is conducive to growing garlic.

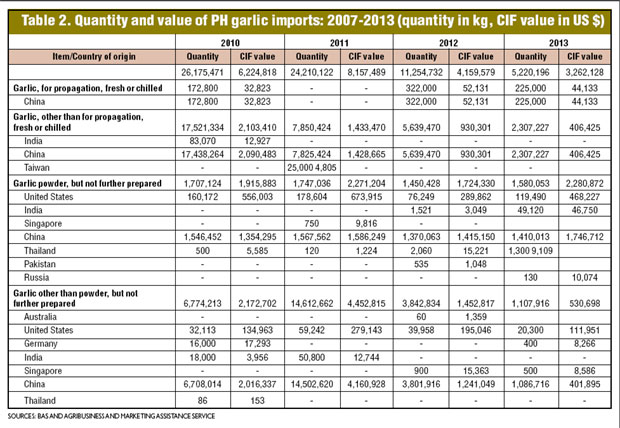

Faced with a supply gap, government has no choice but to allow importation, a practice which harkens back to the Spanish colonial era.

Under this administration, the importation is carefully timed so that the foreign garlic would not arrive during the harvest of local garlic and depress the prices of what our local farmers have grown.

The volume is also pegged to meet the shortfall. The rule is that imports must not elbow out of the market the locally grown.

Protocols in food importation are strictly followed. Import permits are released only to bona fide traders and genuine cooperatives, and after a series of public hearings and consultations with local growers has been called.

Action team

In fact, we have created a National Garlic Action Team as a consultative mechanism on garlic issues. This is composed of local farmers, food processors, consumer groups and government agencies, such as the Bureau of Customs, and the Department of Trade and Industry.

We have to be rigorous in our assessment of supply as there have been cases in the past when the clamor to import large volumes of garlic, with a looming or actual shortage as excuse, was later discovered to be manufactured.

Artificial shortage

In the case of the recent spike in garlic prices, we are investigating if big garlic traders are squeezing supply in order to push prices up and therefore induce an artificial shortage—with the intention of stampeding the government into approving import applications haphazardly.

This kind of market manipulation, we believe, is as injurious as smuggling.

At present, we suspect that the increase in garlic prices is more a product of speculation than a shortage of supply.

Note that the main garlic crop for the year was harvested just last month and this has not been fully absorbed by the market.

The clamor to boost stock is not to respond to present market conditions but to hoard for the lean period, which coincides with the rainy season.

As the rise in the garlic prices is played up by the media, it is but the natural reaction of some farmers and traders to hold on to their stocks and wait for prices to rise further.

We believe, however, that prices will go down and supply will go up once the measures—from boosting production to allowing carefully calibrated imports—to deflate the above-normal garlic prices are implemented.

We are gladdened that growers and traders have responded to our appeal and have started releasing their stocks to the market, some through the fleet of rolling stores we have deployed to public markets in Metro Manila.

Looking forward, the yawning gap between the demand and supply of garlic should prod farmers to diversify to this high-value crop.

At present, only 2,590.68 hectares are planted to garlic, a speck in our farmland inventory.

To most farmers, garlic is an alien crop, and thus it must be aggressively introduced to them as a plant that can bring great yields out of relatively little inputs.

Compared with rice, garlic requires little water, not-so-tedious land preparation, less fertilizer and a less complex postharvest process. If El Niño makes true its threat to visit us this year, garlic, being drought-resistant, can be a replacement crop.

As to income, one demonstration farm run by the Department of Agriculture yielded a net profit of P162,000 per hectare, a return higher than most crops.

What can be done is to use garlic as a fallow crop to rice on areas where irrigated water is not available during the dry season.

Tantalizing

All in all, these potential earnings and comparative advantage of garlic should be tantalizing enough to persuade a farmer to try to reinvent himself as a “Pinoy bawang.”

And when he churns out enough to meet our garlic addiction, we should patronize it over the imported ones.

Like the ones available on the market today, local garlic is cheaper, easy on the pocket and more pungent, making it suitable as an indigenous comfort food.

(Proceso J. Alcala is the agriculture secretary.)