Fundamentalism vs. faith

We used to attend Sunday Mass as a family at Don Bosco, Makati, which also meant confession under the late, stern, sensible Fr. Adolf Faroni, SDB. Every confession could be both a retreat and a sermon. Father Faroni did his research, used theology, minced no words.

He told me once, “There is no space for fundamentalism in the Catholic faith.”

I was surprised. I thought all Catholics were fundamentalists at heart: loud preaching, scrambling over crowds to touch an image, self-flagellation, walking on knees.

It took me years, of both reading and maturing into the faith, to truly unpack the statement.

Its multiple layers revealed themselves over time. Hate the sin, love the sinner. We cannot condemn anyone because we have neither authority nor absolute moral high ground.

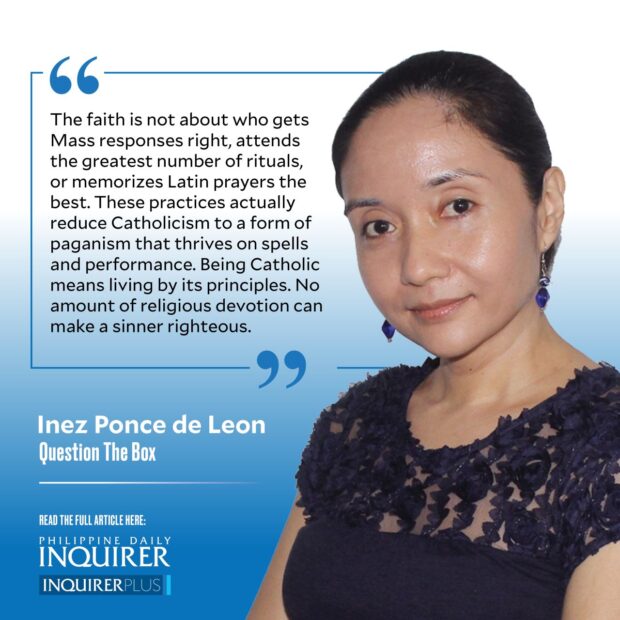

The faith is not about who gets Mass responses right, attends the greatest number of rituals, or memorizes Latin prayers the best. These practices actually reduce Catholicism to a form of paganism that thrives on spells and performance.Being Catholic means living by its principles. No amount of religious devotion can make a sinner righteous. No volume of prayers can wash away malice.

Recently, fundamentalism has been visibly aligned with a tendency to believe in conspiracy theories, such as the existence of a deep state that pulls the puppet strings of those in power, baby-eating and Satan-worshipping world leaders, and microchips in vaccines. Why are such extreme beliefs so attractive to fundamentalists?

The answer seems obvious: Putting faith in an invisible God also makes people believe in phantom villains. The implications, however, run deeper.

Scholars such as Amy Luebbers, Franciszek Czech, and Aden Cotterill, among many others, have studied fundamentalism for years. Fundamentalists rely on rituals, visions, or their own interpretation of traditions to make decisions and pass judgment. Religious fundamentalists tend to believe in conspiracy theories that challenge their moral framework and allow them to practice their faith.

Religion, per se, is not what makes people subscribe to conspiracy theories. Rather, it is “religion understood as a specific element of ideology,” to quote Czech’s 2022 study. It is religion weaponized.

Cotterill, in an op-ed on Australia’s ABC news site, explained modern Christianity’s conspiracy theory obsession. There are three epistemic skeletons that predispose the faithful to espouse such beliefs: faith without sight, or complete trust in God; the folly of the wise, or a belief that the rich, worldly-wise, and powerful are outside God’s grace, which is reserved for the poor and humble; and a belief in the apocalypse and modern day struggle against Satanic forces.

It is not literally these epistemic skeletons, Cotterill argues, that lie at the heart of conspiracy thinking. Rather, it is their abuse: Faith without sight should never be misinterpreted as faith without reason; even the bible calls for evidence-based judgment. The folly of the wise is not for all the wise, but for those who misuse their intellectual and financial gifts for personal gain.

Cotterill quotes Paul’s letter to the Corinthians: Evil can masquerade as an angel of light. There are two dangers, then: assuming that evil is everywhere; but also assuming that something that looks and feels good is also really, truly good.

If I might add: The abuse of these epistemic skeletons is itself fundamentalism. It is the literal reading of texts, whether church doctrine or a country’s laws, to suit one’s purposes. It is ascribing all success as evil, which then provides fundamentalists an excuse to not seek gainful employment. It is worldly arrogance.

To guard against fundamentalism, we go back to the word “Catholic,” which has its origins in the Greek Katholikos: universal, to counter the early heretics who exaggerated their own truths to favor their local churches.

To be devout, then, is not to simply pray, but to strive to live the faith in all its difficulty and grandeur. If one’s devotion depends so much on earthly recognition of one’s acts or beliefs, then it is not devotion, but vanity.

And if one’s faith prompts one to make others suffer, then it is not faith, but fundamentalism — and for that, there is no space in a faith that should be universal.