Dead men do tell tales

Dead men tell no tales is a phrase older than the title of a 2017 film in the “Pirates of the Caribbean” franchise. The phrase has been tracked down to the 13th-century Persian poet Abū-Muhammad Muslih al-Dīn bin Abdallāh Shīrāzī and even earlier to Plutarch in the second century. Murder to silence someone who knows too much is as old as history, but the phrase has become obsolete in the face of modern forensic science. Anyone who has watched “Crime Scene Investigation” documentaries knows that the remains of the dead do tell tales that lead to prosecution and final judgment. These can also revise history.

I first saw medical science at work in Philippine history when Dr. Jose M. Pujalte led a team of orthopedic doctors that exhumed Apolinario Mabini’s bones in 1980. Their analysis: the “Sublime Paralytic” did not lose the use of his legs due to syphilis, as previously whispered about; he was afflicted by polio. Then, there was the opinion of Juan Luna’s younger brother, the toxicologist Dr. Jose Luna, that the great painter’s unexpected death in Hong Kong was due to poisoning. I have a copy of Luna’s 1899 death certificate that gives the cause of death as “angina pectoris,” literally a pain in the chest or a heart attack. Case closed. But then, during a talk delivered to the Philippine Heart Association, I detailed the account of Mariano Ponce who was with Luna at the time of death. Ponce described the symptoms as a sudden splitting headache and vomiting before losing consciousness. These, I was told, are symptoms of a stroke, not a heart attack.

Article continues after this advertisementFour decades ago, a few strands of hair caused a reinvestigation into Napoleon’s death. Six days before Napoleon passed he left these instructions with his personal physician:

“After my death, that cannot be far off, I want you to open my body … I want you to remove my heart, that you will place in spirits of wine and take to Parma, to my dear Marie-Louise … I recommend that you examine my stomach particularly carefully; make a precise detailed report on it, and give it to my son … I charge you to overlook nothing in this examination … I bequeath to all the ruling families the horror and shame of my last moments.”

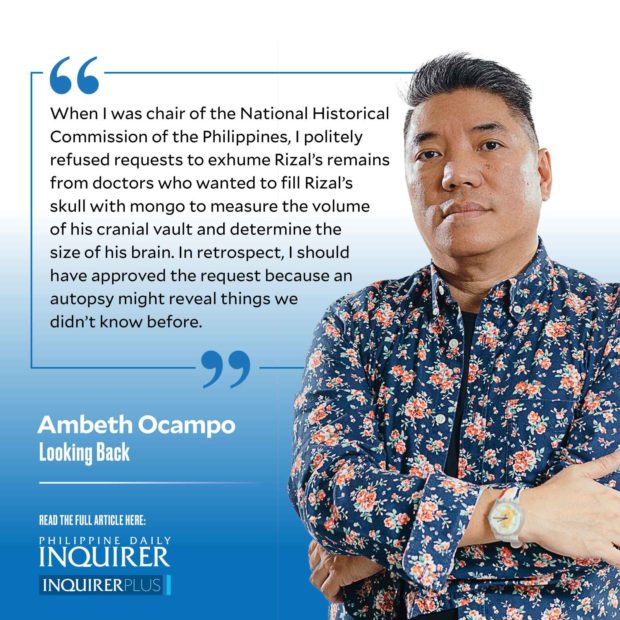

Rizal left final instructions too, most of which were not followed. He wanted to be buried in Paang Bundok; he now lies in the Luneta. He wanted a simple cross over his grave; instead, he got a monument in granite and bronze. He wanted his tombstone to be simple, just his name, date of birth, and date of death; instead, he got wordy texts around the tomb. Finally, no anniversaries please; instead, the president of the Philippines (or representative) lays a wreath and gives him full military honors each year on Dec. 30. When I was chair of the National Historical Commission of the Philippines, I politely refused requests to exhume Rizal’s remains from doctors who wanted to fill Rizal’s skull with mongo to measure the volume of his cranial vault and determine the size of his brain. In retrospect, I should have approved the request because an autopsy might reveal things we didn’t know before.

Article continues after this advertisementMy interest in forensics in history came from a book I read three decades ago that argued: Napoleon did not die of stomach cancer but of arsenic poisoning. After his death in 1821, Napoleon’s unembalmed corpse was buried inside four coffins in St. Helena. In 1840, when his remains were exhumed for return to Paris, it was discovered incorrupt. The uniform he was buried in was totally decayed, but the corpse was perfectly preserved. Witnesses swore, just as Filipinos today remark during a wake, that the deceased appeared to be “just asleep.” Napoleon was not a saint, his incorrupt body was not a miracle. Rather, it hinted at arsenic poisoning that ironically kills the body but preserves the corpse. To cut a long story short, a few strands of hair shaved from Napoleon’s head shortly after his death were analyzed and found to have high traces of arsenic. Recent research examined samples of Napoleon’s hair taken from different times of his life and all of these tested positive for arsenic. This means that Napoleon lived in an environment with a lot of arsenic. It was not the cause of death and could have come from food, medication, or even damp wallpaper painted with a particular green pigment.

One day, I should share historical medical data with forensic pathologist Raquel Fortun, Twitter handle @Doc4Dead, to revise history and reveal tales told by dead men and women.

Comments are welcome at [email protected]

RELATED COLUMN