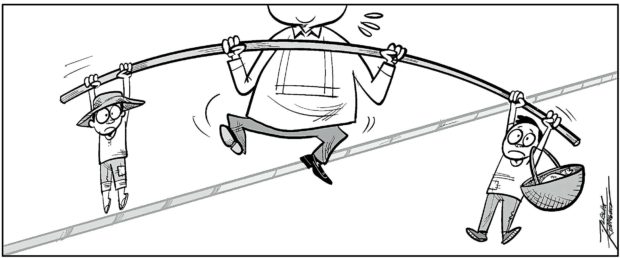

A balancing act

The last few days have seen a string of unwelcome news for Filipinos as the government approved an increase in the suggested retail prices of goods normally bought by typical households from groceries, such as canned sardines, instant noodles, processed canned meat, bottled water, detergent soap, among others.

For the first time since 2016, the prices of bread brands Pinoy Tasty and Pinoy pandesal will go up by as much as P3 as manufacturers grapple with a 45-percent increase in flour prices. This will put more pressure on the wallets of consumers who are still reeling from the one-two punch of high inflation rates since 2018 caused by an artificial rice shortage, followed less than two years later by the African swine fever outbreak that decimated the local hog industry and sent pork prices skyrocketing, and of course the pandemic.

Article continues after this advertisementThe Department of Agriculture also approved a plan to import 60,000 tons of small pelagic fishes such as round scad (“galunggong”) and mackerel to make up for the anticipated supply shortages caused by Supertyphoon “Odette’’ last year, aggravated by the annual fishing ban that is being imposed to allow fish to spawn and stocks to recover.

Importation as a means of counteracting high local prices has been the go-to move of the Duterte administration’s economic managers in recent years, as evidenced by their policies on allowing greater imports for rice and pork.

Importation is now about to be used to avert a shortage of fish, and the “Livestock Development and Competitiveness Law of 2021” has been proposed in Congress to bring down local meat prices, which are some of the highest in the Asean region.

Article continues after this advertisementAs the law of supply and demand dictates, greater importation will result in more of the needed goods in the local market which will, in turn, result in lower prices since there will be no compelling reason for buyers to bid up the prices of a limited supply of goods. That’s great news for consumers, but unwelcome for producers who will see their profit margins shrink or, in some cases, vanish altogether.

Clearly, it is impossible to make everyone happy in this situation as favoring consumers with unfettered importation will wipe out local producers, while favoring these producers with the status quo to high import tariffs will result in consumers unnecessarily bearing the burden of high prices.

What’s needed is balance.

Consumers’ incessant clamor for lower prices is putting immense pressure on policymakers to find rapid solutions like importation without well thought out mechanisms for protecting the local production sector from the brunt of market forces.

Producers, meanwhile, must realize that many players in their sector are simply uncompetitive against imported products, most of which are sold much cheaper locally even with the cost of shipping them in from overseas. And no matter how much consumers want to patronize local products, in the long run, price will be their main determinant for buying decisions.

It is the most basic economic problem: how to allocate scarce resources to satisfy unlimited needs.

In the case of the local economy, there is the constant tug of war between the need to provide Filipino consumers with basic goods at the cheapest possible prices and the need to provide Filipino producers of these basic goods—often impoverished farmers and fisherfolk—with a level of return that will compensate them commensurately and keep them engaged in the production process.

The economic managers of the Duterte administration are on the right track in their move to liberalize the importation of key food items to bring down consumer prices over the long run. But careful effort must be made to convince all stakeholders to buy into the idea.

The danger is for policymakers — in their desire to ram the policies through the legislative mill in the last few months of the Duterte administration — to go in ham-fisted and implement the right solution with little regard for winning over farmers, fisherfolk, livestock producers, and others who will be adversely affected by cheaper imports.

By investing effort into making all sectors understand the rationale for its policies, the economic managers can potentially fix the structural weaknesses of the country’s economy. Or they can bludgeon farmers, fisherfolk, and livestock into submission now, squander the chance to implement a much-needed long term solution and see the problem resurface a few years down the road, possibly in the form of a populist government which will roll back all the so-called reforms in exchange for votes.

Our policymakers should allow market forces to take control of the economy. But market forces must be broken in as gently as possible to give adversely affected sectors a fighting chance. Anything less than that will simply be kicking the can down the road.