Right to disconnect

Governments and companies around the world over the last two years have come up with measures to confront the challenges that the novel coronavirus posed, drastically changing the way of doing things.

For example, the resulting lockdowns that limited the mobility of people, necessary to control the spread of COVID-19, made technology an indispensable part of the so-called new normal so the economy could continue functioning, and students’ education and company workflows would have minimal disruptions, thus: online banking and shopping, blended learning, and work-from-home (WFH) arrangements.

Article continues after this advertisementOn the upside, this has made things much more convenient. But this also gave rise to many issues relating to poverty and accessibility on one end of the spectrum, and the impact on people’s mental health of an “always-on” culture on the other end.

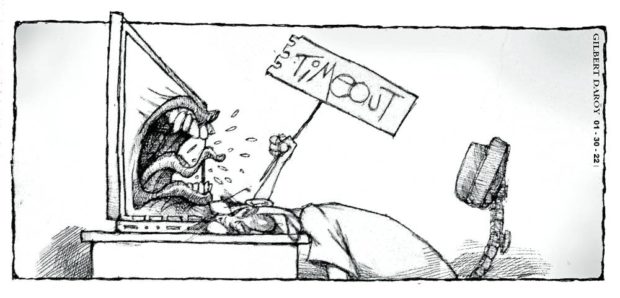

Against this backdrop of an “unli-work from home,” a bill has been filed at the Senate proposing the “workers’ rest law” that seeks to define “rest hours” of employees, and prohibits employers from exacting work or contacting workers without their consent.

“While we recognize the benefits of work-from-home and telecommuting arrangements, they have thinned the line between work and personal space and time. Sometimes, technology and work-from-home arrangements distort the idea of work and home from the point of view of the employees,” the explanatory note of Senate Bill No. 2475 filed by Sen. Francis Tolentino stated.

Article continues after this advertisement“The blurring between working time and private time has become more pronounced during the pandemic because of the increase in the number of employees on a work-from-home or telecommuting arrangements,” it added.

The bill acknowledges that because of WFH arrangements, the home no longer serves as a space to destress after work, and technology has only exacerbated it putting employees “at the beck and call of their employers,” overreaching beyond the regular work hours through phone and email.

It emphasizes that normal work hours should not exceed eight hours a day as provided under the labor law, or not over 12 hours a day under a compressed workweek setup. During these rest hours, and unless with employees’ consent, employers should not require them to work, including compelling them to attend seminars or meetings, or penalize them for not responding to communications received during rest hours.

Violators will be required to pay affected workers P1,000 each per hour of work rendered during the prescribed rest hours, and a prison sentence of not less than one month but not more than six months, and a fine of over P100,000 for employers who discriminate employees who choose to assert their rights.

The proposal, however, excludes domestic helpers, those in the personal service of another, output-based workers, and field personnel defined as “non-agricultural employees who regularly perform duties away from the principal place of business or branch office … and whose actual hours of work in the field cannot be determined …” (Field personnel though do not include employees who are on WFH arrangement and telecommuting employees covered by Republic Act No. 11165 or the Telecommuting Act.)

The WFH setup is not entirely new and has been around since the early 2000s as more companies started to recognize the importance of work-life balance. But several studies have shown that working from home, while it has allowed employees more flexibility and less stress from the daily commute, has also led to an increase in the average daily work time by at least 2.5 hours or even more for those who are unable to detach from work.

Recognizing this, many countries particularly in Europe have passed laws even before the pandemic giving workers the “right to disconnect” from digital gadgets. In the Philippines, former congressman Winnie Castelo has filed a similar measure in 2017, but the proposal did not prosper beyond the committee level.

This worker-friendly measure becomes even more significant considering that up to 49 percent of employees in the Philippines have indicated a preference for working remotely in a study conducted by SEEK Asia in the last quarter of 2020. The same study also showed the country’s significant digital shift from only 52 percent working remotely before the pandemic to 85 percent as of 2020.

While there are certain industries including media where disconnecting may be unrealistic given the nature of work, a measure granting employees the right to disconnect becomes even more imperative in the post-pandemic reality where companies are looking at transitioning to a hybrid work setup—meaning requiring employees to report to the office but also allowing them to work from home on certain days.

As the world embraces the new normal and gears toward rising from the crises brought about by COVID-19, the workers on whose backs this recovery will largely depend are crucial. It is but only proper to protect their rights and their mental health to ensure a productive workforce in the post-pandemic era.