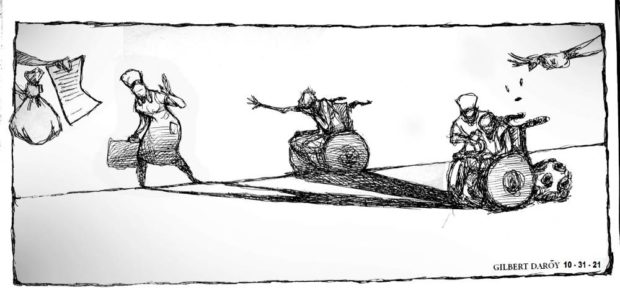

Exodus of nurses

Editorial cartoon

How ironic that the world’s so-called biggest supplier of nurses may soon be facing a shortage, and in the middle of a pandemic at that. But it’s no surprise that many Filipino nurses are fleeing the country, leaving their families behind, and seeking employment overseas where they get paid as much as 10 times more compared with their paltry earnings here.

In the past few weeks alone, up to 10 percent of health workers have reportedly resigned to leave for jobs abroad. The resignations are nothing new — they have been happening even before the pandemic—but the enormous strains inflicted on medical frontliners by the pandemic, and the neglect many have endured due to delayed benefits and broken promises by the government, have triggered an exodus of nurses. If this persists, warned Dr. Jose Rene de Grano, president of the Private Hospitals Association of the Philippines Inc., it will further strain, or worse, paralyze the country’s health care system in the next six months.

Article continues after this advertisementTo control the stream of medical workers leaving for abroad, the government imposed an annual cap on overseas deployment, 5,000 a year, but even that had already been reached by June. “We fear that if more health care workers will be allowed to leave and we cannot find a replacement immediately, we may run out of health care workers,” said De Grano.

The country’s low pay for nurses, as well as mental and physical exhaustion, are the top reasons cited by many such workers for quitting. Most of the resignations have been happening in private hospitals, where the minimum wage for nurses is P537 daily or, according to computations by the Filipino Nurses United (FNU), P11,814 a month. Those who have resigned either move to public hospitals, where they could at least benefit from the salary standardization law (an entry-level nurse gets from P8,000 to P13,500 a month); move to other industries that pay higher; or go overseas. Nurses get a monthly average salary of $3,800 (almost P200,000) in the United States, 1,662 British pounds (around P116,000) in the United Kingdom, and C$4,097 (at least P167,000) in Canada.

More than the higher pay, local health workers have been suffering from low morale because they see the government’s appalling attitude toward them. They are asked to put their lives at risk during this pandemic without proper protection and adequate compensation. There’s the well-known case of Maria Theresa Cruz, a nurse in Cainta who died of COVID-19 last year even before she received the hazard pay granted by the government. The pay amounted to a shocking P60 daily.

Article continues after this advertisementThe Department of Health (DOH) said that, as of September, it has released up to P14.3 billion worth of benefits covering hazard pay, special risk allowance, and meals, accommodation, and transportation allowances for two periods from Sept. 15 to Dec. 19, 2020, and Dec. 20, 2020 to June 30, 2021. That release was made after health care workers (HCWs) had to take to the streets to demand what’s due them. And yet even today many nurses and health workers claim they have yet to receive their benefits, said Jao Clumia of the St. Luke’s Medical Center Employees Association.

The Philippines is certainly not the only country whose health care system has been burdened by the COVID-19 pandemic. Countries across the world have seen widespread burnout among frontline workers. But while the DOH is still debating proper compensation for HCWs, shuffling paperwork over inexplicably delayed benefits, and answering charges before the Senate on the mismanagement of COVID-19 funds, other governments are looking at how they can further improve the work environment in their health care systems. In the US, for example, where a 10-percent vacancy rate in nursing positions has been reported, hospitals are offering incentives and sign-on bonuses for nurses, as well as free mental health support and short-term therapy for essential workers.

Maristela Abenojar, president of FNU, said in a radio interview that she can’t blame other nurses for leaving: “Kahit wala pang pandemic, meron na po talagang nagsialisan ng bansa … pero eto po ay medyo lumala ngayong may pandemya gawa po ang ating mga nurses ay bahagi ng mga manggagawang pangkalusugan na naiipit din sa krisis ng ekonomiya na nararanasan natin ngayon.” Abenojar noted that a nurse’s salary, which can go as low as P8,000-P10,000 a month in private hospitals that do not follow the minimum wage law, is clearly not enough to support a family.

But banning nurses from leaving is not the solution, she said. The fair remedy is to raise their compensation and release benefits on time. Nurses will not be motivated to stay if their pay remains meager, stressed Abenojar. “At yung mga benepisyo na pinapangako, at mga benipisyo na nakasulat naman sa batas, dapat ay ipinapatupad at timely na nire-release kasi kahit papaano nakakatulong yan sa [aming] survival.”