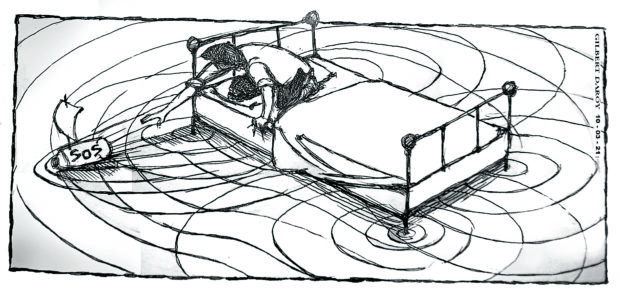

‘The future is frightening’

Editorial cartoon

Last Sept. 24, hundreds of protesters across the country joined a global climate strike demanding urgent action from governments to address climate change. Among them were fisherfolk and young environment advocates who marched to the site of the controversial Manila Bay dolomite beach. As the protesters wearing face masks raised their fists and called for a more forceful response to the climate crisis, an excavator tractor stood idle in the background beside a pile of dolomite — a reminder of the billions wasted that should have gone to more beneficial projects like, say, buying COVID-19 vaccines or helping coastal communities adapt and cope with the extreme weather events brought about by climate change.

“We’re striking in an area that will likely be underwater before I turn 50,” said Yanna Mallari, one of the protesters, as reported in The Guardian. “Those are the kinds of challenges my generation is facing. We are here to call for action and inclusive adaptation policies that prioritize people and planet.”

Article continues after this advertisementThe Manila Bay Area continues to rise — by 12.13 mm per year, about four times the global average, according to the Coastal Sea Level Rise Philippines Project. The rise could even be higher in low-lying areas such as Caloocan, Navotas, Malabon, and Venezuela, worsened by population growth and endless urban construction.

Rising sea level also threatens more than half of the country’s population, making the Philippines among the most vulnerable to the climate crisis, which — per the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s Sixth Assessment Report released last August—was already “widespread, rapid, and intensifying.” The country also ranked fourth in the Global Climate Risk Index among nations most affected by extreme weather events from 2000-2019, reporting a total of 317 weather-related events over that period, the highest among the most affected countries.

“The country’s archipelagic structure exposes it to other natural hazards, such as storm surges, tsunamis, floods, and landslides,” said the Oscar M. Lopez Center, in its analysis of IPCC’s latest report. “About 60 percent of the country’s population and 10 percent of major cities are situated along the country’s vast coastlines.” Worse, due to its lower coping capacity, the Philippines will need more time to rebuild and recover from these extreme weather events compared to more developed countries.

Article continues after this advertisementThis week, Inquirer’s two-part special report highlighted the plight of Metro Manila’s poor coastal communities that face rising sea levels and the prospect of being displaced, even though many local governments appear to have no concrete or comprehensive long-term plans to prepare for such disruptions. The Inquirer report noted that only 702 out of the 1,715 provincial, city, and municipal governments have submitted their local climate change action plan (LCCAP) to the Climate Change Commission as of Sept. 1. Among Metro Manila LGUs, only Marikina, Pasig, Quezon City, Caloocan, Makati, and Malabon have submitted their LCCAP. Manila’s city council has reportedly yet to approve its LCCAP.

Many leaders dilly-dally because the climate issue lacks the drama brought about by calamities such as Supertyphoon “Yolanda.” But “that needs to change because even if it is slow, it is potentially irreversible or even harder to grapple with,” said Red Constantino, executive director of the Institute for Climate and Sustainable Cities.

Anxiety over the looming climate catastrophe has become particularly pronounced among young people, according to a recent global study by a group led by the University of Bath and the Stanford Center for Innovation in Global Health. “Some 45 percent of the 10,000 young people surveyed across 10 countries… said anxiety and distress over the climate crisis were affecting their daily life and ability to function,” reported CNBC. “Three-quarters of respondents aged 16-25 felt that the ‘future is frightening,’ while 64 percent of young people said that governments were not doing enough to avoid a climate crisis. In fact, nearly two-thirds of young people felt betrayed by governments and 61 percent said governments were not protecting them, the planet, or future generations.”

No wonder groups like the Youth Advocates for Climate Action Philippines are making their voices heard in the local climate movement. The group has called for better environmental policies and raised alarm over projects that it said would be destructive to the environment, such as the array of planned reclamation projects in the Manila Bay area. Last August, the government announced that five land-reclamation projects in Manila Bay within the territorial waters of Cavite were already in the pipeline. But fisherfolk in the area warned that the project will destroy mussel and oyster farms as well as displace thousands of families. Their appeal: “‘Wag n’yo nang gatungan ang krisis ng klima.”