Freedom is not free: A look into Filipino Independence Day

INQUIRER FILE PHOTO

On June 12, the Philippines commemorates Independence Day once more. The current legal basis of this holiday is Republic Act No. 4166, which changed the date from July 4 to June 12. However, the Filipino experience of fighting for independence may seem a peculiar one for the rest of the world.

For instance, the United States from Britain (1775-1783), the nations of South America from Spain (1810-1833), and Romania from the Ottoman Empire (1877), among others, all fought for and won their armed struggle for independence.

Article continues after this advertisementAs for the Philippines, we formally celebrate our independence on a date when we did not even win it yet. What are we independent from? Should we celebrate it in the first place? This led to criticism that we are remembering an empty and false independence day.

If that is the case, when should we celebrate Filipino independence? A number of dates have been forwarded throughout the years, and let us take a look at some of them.

April 27

On April 27, 1521, what is now the Battle of Mactan saw the local ruler Lapu-Lapu emerging victorious over the outnumbered Spanish troops led by Ferdinand Magellan. To this day, Lapu-Lapu is widely regarded as the hero who “fought against foreign domination.” This is why some may consider the date as our rightful day of independence. As a consolation, Proclamation No. 200 declared April 27 as Lapu-Lapu Day.

Article continues after this advertisementOf course, there are issues that may be looked at before we can proclaim April 27 as independence day. Taking the event into context, engaging in battle is not a matter of last resort. It is an opportunity to assert supremacy. The battle involved large numbers of troops. If we are to believe foreign accounts, both Humabon and Lapu-Lapu may have had as many as 3,000 to 4,000 each. Magellan only had 60. However, precolonial diplomacy shows that perception of strength is more potent in negotiations than actual strength. This is why Magellan risked it despite being outnumbered.

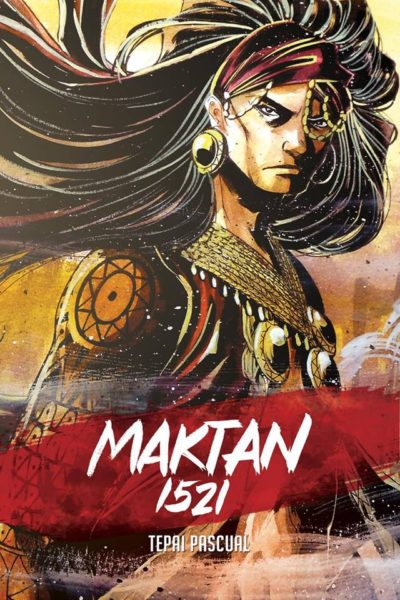

Cover of “Maktan 1521,” a comic depicting the Battle of Mactan. Photo courtesy of Tepai Pascual

Whether he was confident of their technological superiority or he wanted to impress his new allies (Rajah Humabon and company), Magellan took a costly gamble. Humabon, for his part, was just too wise not to participate in the battle. One should also explore the intent of the Magellan expedition. While they did claim the islands (by naming it, persuading the rulers to obey the Spanish king, and baptizing the people into Christianity), the main objective is to reach the Spice Islands (Moluccas/Melaka), and circumnavigate the world to prove that the earth is not flat. Besides, if the Spanish never got to occupy Mactan anyway, then Lapu-Lapu would not have to declare independence from anyone or anything. All the polities in the Philippines at the time were independent of each other, and battles between them are commonplace. In the Filipino perspective, the foreigner Magellan is no exception. Instead, he became a player in the existing diplomatic and military norms being practiced at the time.

How about Lapu-Lapu and his agenda? If we are to believe Cebu folklore, it seemed that Lapu-Lapu was a foreigner, and Rajah Humabon was well established in Cebu when Lapu-Lapu arrived from Borneo. Lapu-Lapu asked Humabon for land to develop, which may go to show that Humabon was the authority figure in the area. Humabon offered Opong (Mactan), but Lapu-Lapu preferred Mandawili ((Mandaue) in mainland Cebu. When the Spanish arrived, it appears that Lapu-Lapu had to settle with Mactan, and Humabon refused his request. Was Lapu-Lapu a threat to Cebu? To an extent, there is even the notion that Lapu-Lapu was a pirate chief. Was he involved in pangangayaw (raids) which terrorized the islands?

Looking at the situation this way, it would seem that Humabon had misgivings to Lapu-Lapu, which the latter did not forget. Lapu-Lapu may have also known that Humabon himself was a foreigner to Cebu. Humabon (or Sri Hamabar) was grandson of Sri Lumay (or Rajamuda Lumaya), a half-Tamil migrant from Sumatra. If Lapu-Lapu was indeed a foreigner himself, then how can he be regarded to fight against “foreign” domination? The battle would turn out not only as a fight against Magellan, but also a fight against Humabon.

Continue reading at Philippine Historian to know the rest of the possible dates Filipinos could celebrate their independence.

ThINQ is the Inquirer's attempt to highlight in the public space the distinct viewpoints contributed by bloggers covering a wide range of topics and issues.

If you'd like to be included in the ThINQ blogger network, e-mail [email protected] with the subject "ThINQ Membership" along with your blog's URL and topics your blog currently covers.