AFP-PNP leadership in the 21st century

In the 19th century, the captain general of the Filipino Army (equivalent to present-day AFP chief of staff) was Gen. Artemio Ricarte. He was elected to the position at the Tejeros Convention of March 1897 and served for two years (1897-1899).

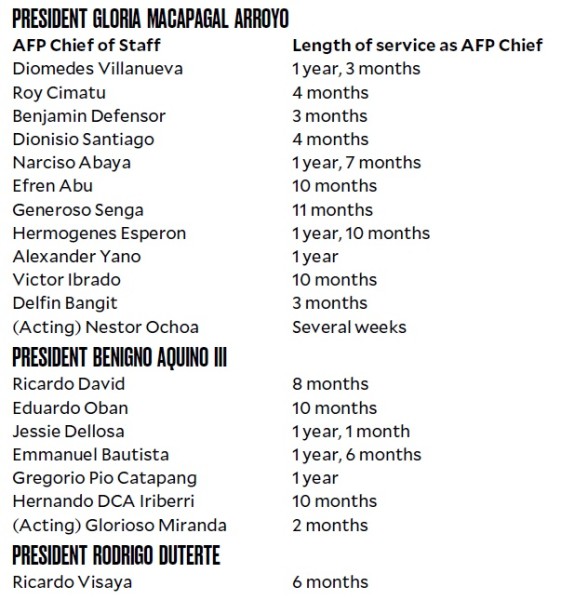

In the 21st century the longest-serving AFP chief of staff was Gen. Hermogenes Esperon who served for one year and

10 months. The shortest tour of duty was for a period of

three months.

In the 19th century, our revolutionary leaders kept the captain general at his post for two years. In the 21st century, our political leaders came up with a “revolving door” policy designed to ensure easier manipulation of the AFP leadership for their personal advantage.

The 21st century began on Jan. 1, 2001, and will end on Dec. 31, 2100. In the first 16 years of the new century, the AFP has had 19 chiefs, and two acting chiefs of staff.

In just one year during the Arroyo administration (2002) the AFP had three change-of-command ceremonies at Camp Aguinaldo, installing three new chiefs. With such a fluid situation at the top, it was the perfect environment for underlings to engage in mischievous activities. Since the commander was not going to be around too long and was focused on protecting the seat of power and its occupant, not much thought was devoted to any performance audit or review. As a consequence, the

In just one year during the Arroyo administration (2002) the AFP had three change-of-command ceremonies at Camp Aguinaldo, installing three new chiefs. With such a fluid situation at the top, it was the perfect environment for underlings to engage in mischievous activities. Since the commander was not going to be around too long and was focused on protecting the seat of power and its occupant, not much thought was devoted to any performance audit or review. As a consequence, the

“revolving door” policy led to one of the worst abuses in the history of our Armed Forces.

In 2003, US customs authorities confiscated undeclared foreign exchange being brought into the United States by family members of AFP comptroller Maj. Gen. Carlos Garcia. The discovery would have far-reaching consequences for the Armed Forces. It would be a contributory factor in the tragic, self-inflicted death of Gen. Angelo Reyes.

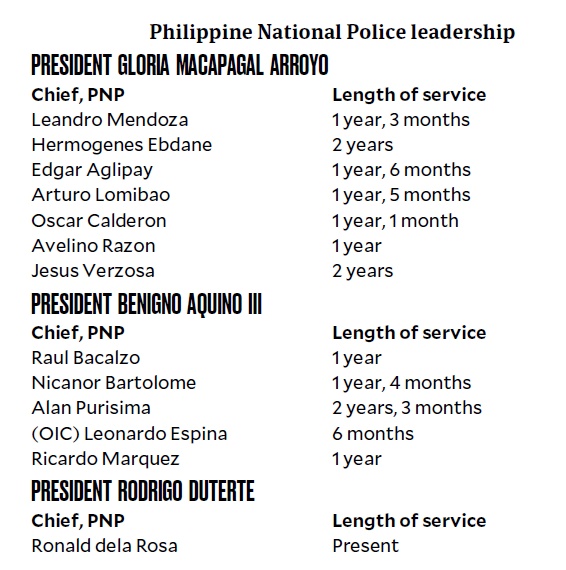

In the case of the Philippine National Police there is only a slight difference. In the first 16 years of the new century, the PNP had 12 chiefs and one officer in charge. The longest-serving chief was Alan Purisima who stayed for two years and three months. The shortest tour of duty was one year.

Perhaps the greatest setback suffered by the PNP since the establishment of the organization was the 2015 Mamasapano tragedy. The PNP lost 44 Special Action Force troopers in an operation aimed at capturing two international terrorists, Marwan and Basit Usman, both bomb-making experts belonging Jemaah Islamiyah.

In any organization, military or civilian, no substantial, long-lasting reforms that truly bring about transformation can succeed under short-term leadership. Whatever changes come about from such management policies are mostly cosmetic in nature and temporary. It does not require a management expert to appreciate this.

Let me also add that fixed terms for our AFP and PNP chiefs will not be the cure-all for our problems. I have focused on this particular aspect of leadership because it represents the so-called “low-hanging fruit” that can easily be harvested. In fact, during President Aquino’s term both chambers of Congress passed a bill providing fixed terms for the AFP chief and service commanders. Unfortunately, for reasons of his own, Aquino

vetoed the measure. Perhaps, in tackling this problem, a fixed term for the PNP chief should also be considered.

One last word. Many of those who served as AFP chief and PNP chief were competent, hardworking and dedicated public servants. We owe them a debt of gratitude.