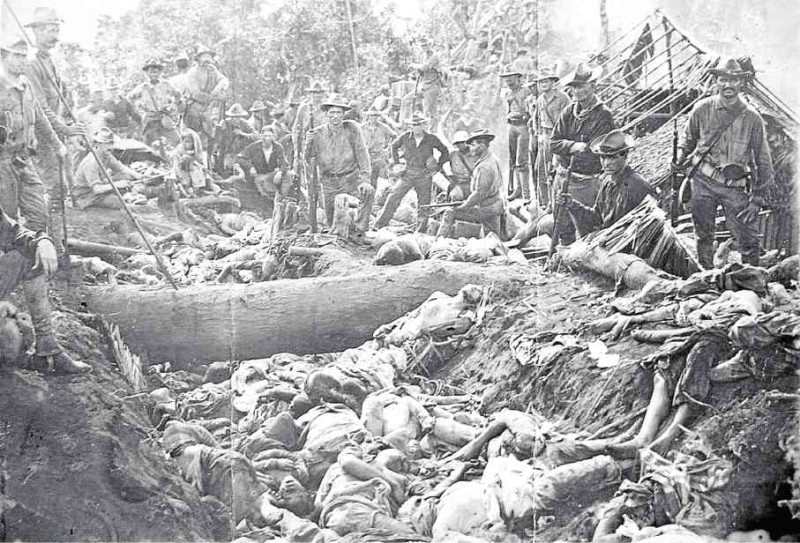

100 YEARS AGO IN JOLO Fallen Moros—men, women and children, who resisted US colonial rule—were piled five deep in the trenches of the crater of an extinct volcano, Bud Dajo, where they had been mowed down by artillery, machine gun and rifle fire from US forces. Many of the Moros had as many as 50 wounds.

IN AN unprecedented and historic fashion, President Duterte made a pointed reference to the American “pacification” of Mindanao in the 1900s to demonstrate the human rights record of the United States.

In turn, his statement has generated much public attention—quite detailed in social media circles—to the US war of aggression and its attendant human rights transgressions, and also to the oft-forgotten Moro resistance to the US intrusion and the role Mindanao played in opposing the US war.

‘Pacification’ campaigns

The American military attacks on Bud Dajo in 1906 and Bud Bagsak in 1913 in Jolo bring to the fore, in a most graphic manner, how the Americans carried out “pacification” campaigns in the country.

The Philippine Commission of 1906 reported to the US Secretary of War the encounter at Bud Dajo. The report says “disaffected datus” of the island had been “joining themselves together in an extinct crater at the top of Mt. Dajo, near the town of Jolo, and had gathered about them the lawless of all the neighboring regions.”

The “joining together” quite appeared to be a collective refusal to submit to the American campaign to place all Filipinos under US dominion, a major measure of which was the creation in 1903 of the Moro Province (Act No. 787), with all its attendant instruments of control, including imposition of the cedula tax. The province was placed under Maj. Gen. Leonard Wood as governor, who also served as commanding general of the US Army department of Mindanao and Sulu.

Moro resistance

The US intrusion was promptly met with stiff Moro resistance. From 1903, General Wood had to contend with Moro attacks, mainly in Cotabato and Sulu, directed against the American campaign. The pattern in the conduct of the US campaign was bombardment with heavy artillery and assaults with “quick-firing” (machine) guns, resulting in the slaughter of Moro communities, such as in Kudarangan, Laksamana and Bud Dajo.

The attack on Bud Dajo was part of Wood’s punishing reprisals for Moro raids on American forces. In Bud Dajo, “(d)etachments … of United States troops, assisted by US Marines, constabulary …, assaulted the stronghold and exterminated the band. The position was first shelled by a naval gunboat and then assaulted by the combined government forces. Among those in the crater were more or less Moro women and children, who were unavoidably killed.

Shelling

“The shelling … necessarily killed all who came in the way of missiles and the women fought beside the men and held their children before them. The Moros, men and women, were all fanatics, sworn to die rather than to yield, and certain, as they believed, of a glorious reward in the world to come if they died killing Christians.”

The language of the report definitely does not elevate the Moros, described as “lawless” and “fanatics.” It is noteworthy though that it refers to women and children as “unavoidable” casualties. Though the report does not say, it indicates that the subject of the assault was a community in retreat.

Vic Hurley, an American who stayed in Mindanao for seven years and wrote a book on the Moros in 1936 presented a more detailed account of the encounter, based on “acquaintances of elders of many Moro barrios” and various histories of the Philippines then extant.

Reinforced by 2 batallions

He writes: “A large band of Moros fortified Bud Dajo and defied the authorities to subject them to any law. The American garrison at Jolo was reinforced by the addition of two battalions of infantry and preparations were made for a decisive assault on the Moros….

“The battle began on March 5. Mountain guns were hauled into position and 40 rounds of shrapnel were fired into the crater to warn the Moros to remove their women and children.”

Kris, spear

Three columns of American troops moved up Bud Dajo from different sides and encountered fierce resistance from barricades blocking the approach to the crater. When overwhelmed with heavy bombardment and sniper fire, the Moros “sallied forth into the open with kris and spear.”

On the second day, in the approach taken by a certain Major Bundy, “200 Mohammedans died here before the quick-firing guns and the rifles of the attackers.”

Fixed bayonets

On the third day, “(a)fter the heavy bombardment had accomplished its purpose, the American troops charged the crater with fixed bayonets. The few Moros left alive made hand grenades from seashells filled with black powder and fought desperately to stem the charge. But the straggling krismen were no match for the tide of bayonets that overwhelmed them and hardly a man survived that last bloody assault.

Piled five deep

“After the engagement the crater was a shambles. Moros were piled five deep in the trenches where they had been mowed down by the artillery and rifle fire. The American attack had been supported by two quick-firing guns from the gunboat Pampanga and examination of the dead showed that many of the Moros had as many as 50 wounds. Of the 1,000 Moros who opened the battle two days previously, only six men survived the carnage.”

Hurley’s judgment of the event is significant. He states: “By no stretch of the imagination could Bud Dajo be termed a ‘battle.’ Certainly the engaging of 1,000 Moros armed with krises, spears and a few rifles by a force of 800 Americans armed with every modern weapon was not a matter for publicity. The American troops stormed a high mountain peak crowned by fortifications to kill 1,000 Moros with a loss to themselves of 21 killed and 73 wounded! The casualty reflects the unequal nature of the battle.

“The Moros had broken the law and some punishment was necessary if America was to maintain her prestige in the East, but opinion is overwhelming in the belief that there was unnecessary bloodshed at Bud Dajo.”

Hurley’s account indicates that the subject of the attack was in fact a sizable community. Women and children stood side by side with the men. The number of people, about 1,000, was too large for a “band.” The weaponry did not reflect a professional formation under arms.

Gatling

It appears those who fought fiercely the invaders were the menfolk defending the community, which reeled from heavy artillery bombardment, quick firing (from machine guns, the Gatling or a later type), and rifle fire (from the Krag or a later Springfield). The “band” was a community that refused to submit to American colonial governance.

The military assault turned out as a massacre of a largely civilian population defending themselves with whatever they could lay their hands on—krises, spears, some rifles and improvised explosives.

Slaughter

Hurley’s mention of many fallen bodies riddled with bullets (with “as many as 50 wounds”) also points to the slaughter. It appears that the defenders were so overwhelmed by heavy firepower that their actions signified willing submission to death as they “sallied forth into the open.”

In 1913, a similar encounter took place in another hilly point in Jolo, The Philippine Commission of that year reports that “(i)n Jolo the authorities of the Moro Province, with the invaluable cooperation of the United States Army and the Constabulary, were engaged throughout the year in carrying out the disarmament of the Moro population. Such opposition as was encountered centered in a small portion of the island known as Lati Ward …. The population, influenced by the disorderly element, when it appeared that movements of troops were to be made, stampeded to the number of several thousand, including women and children to Bud Bagsak … and flatly declined to surrender individual criminals or arms.

“Finally, after a long period of negotiations and maneuvering, advantage was taken of a time when all but a defiant minority, including practically all the noncombatants, had left the stronghold and the latter was on the morning of June 11, 1913, carried by a surprise attack of a force of American troops and Scouts…”

Bud Bagsak bombardment

As in Bud Dajo, the attack commenced with heavy bombardment of the cottas (forts) surrounding the main cotta of Bud Bagsak. One by one, the cottas fell to shelling and infantry assaults.

The campaign to capture it took five days. Putting up fierce resistance against the Americans, the Moros “would rush out in groups of 10 to 20, charging madly across 300 yards of open country in an effort to come hand to hand with the Americans …. In each instance, the charging Moros were accounted for long before they reach the American trenches.”

Pershing’s final assault

On the fifth day, the American forces under Gen. John Pershing made the final assault.

Hurley writes: “The mountain guns opened up for a two-hour barrage into the Moro fort, and at 9 o’clock in the morning the troops moved up the ridge for the attack. The heavy American artillery shelled the Moros out of the outer trenches supporting the cotta of Bagsak and the sharpshooters picked them off as they retreated to the fortress. After an hour’s hard fighting, the advance reached the top of the hill protected by the fire of the mountain guns, to a point within 70 yards of the cotta.

“To cover that last 75 yards required seven hours of terrific fighting. The Moros assaulted the American trenches time after time only to be mowed down by the entrenched attackers….

“About 500 Moros occupied the cottas at the beginning of the battle of Bagsak and with few exceptions they fought to the death.”

Like Bud Dajo, the encounter at Bud Bagsak eloquently speaks of Moro heroism and martyrdom in the face of a brutal war of conquest. At Bud Bagsak, it is not clear from the account of the Philippine Commission if women and children were included in the 500 or so Moros exterminated by the American assault.

Women, children

While it reports of “noncombatants” being removed from the area, Hurley, however, points to the greatest difficulty in separating the women and children from the men at war.

“So long as the Moros saw that the American troops were inactive and in barracks many of the women and children would be sent down to work in the fields, but at the first suggestion of an American expedition all of the noncombatants would be recalled to the mountains. As General Pershing had stated, when the Moro makes his last stand, he wishes his women and children with him …”

The military campaigns against the Moros were part of the overall plan of the Americans to assert complete control over the archipelago after the establishment of civil government in 1901. They, however, found formidable day-to-day resistance from the Moros. Before the massacres at Bud Dajo and Bud Bagsak, no American was safe, armed or unarmed, away from the garrisons in Muslim Mindanao. The creation of the Moro Province in 1903 became the basis for campaigns of suppression on the island.

Resistance in Luzon, Visayas

In the larger picture, stiff Moro resistance complemented similar organized resistance in Luzon and the Visayas, such as in Samar where Americans engaged in the burning of villages and rice granaries.

US President Barack Obama acknowledged two weeks ago in Laos the US “shadow war” in Indochina. Perhaps it is time for the United States to take another look at this oft-forgotten war at the turn of the 20th century and acknowledge its transgressions on the then newfound sovereign state of Republica Filipina. American anti-imperialists at that time, like Mark Twain, rejected the war and the atrocities it unleashed on the Filipino people.

Recounting the stories of Bud Dajo and Bud Bagsak adds to greater public knowledge a significant detail in the Philippine narrative of becoming a sovereign nation, the spirit of which resonates to this day.

(Ferdinand C. Llanes, Ph.D., is professor of history at the University of the Philippines Diliman. This piece is based on an article published on the web-based “Our Own Voice Literary/Arts Journal,” April 2003. He can be reached at bonifa

cio1959@yahoo.com.)