I remember, as a wide-eyed 10-year-old, braving the sweltering heat of the afternoon sun to squat beside a long, black box situated just outside my father’s entomology office at the University of the Philippines Los Baños. I would squint at the box’s glass display panel to behold a squirming mass of bees making their way through a maze of honeycombs dripping with honey. At the far end of the box was a small opening, in which bees would either alight or depart like miniature jets: fast, precise, and seemingly effortless.

The activities that could be observed in the box were mesmerizing, and the buzzing cacophony (at times a slow murmur, then swiftly rising to a crescendo, as if directed by an invisible conductor) reminded me of a grade-school classroom bursting with the hubbub of conversation.

My father would snap me out of the reverie by standing beside me, and after failed attempts to direct me to the shade, would proceed to explain the dynamics of the colony. I was particularly interested in the “waggle-dance,” and I would peer excitedly at what, my father would point out, were the beginnings of the dance by newly-arrived bees. It would start with just one bee or a group, and eventually be replicated by the rest of the bees in the hive. The secret language of tail-wiggling and turbo-wing-flapping was critical to the colony’s survival. I was amazed when my father said that by decrypting this seemingly random dance, bees are able to ascertain the distance and type of nectar and pollen.

Years later, going through the motions of project management, I would remember the organizational strength and rigidity of the bees—information gathering, transmittal, dissemination—all accomplished by wide-reaching reconnaissance flights and the organic grace of the waggle-dance. It all seemed so easy, so instinctive, and so precise. It was nature’s version of teamwork.

I am blessed to have worked in a variety of settings that encouraged critical thinking and teamwork, especially when it came to objectives-setting and problem-solving. In my first job as a teacher at Ateneo de Manila High School, I had to wrack my brain to think up innovative ways to deliver the content of my lesson plan. At the same time, I had to find ways to align topics with the Ignatian ideal of being a man for others—something that the senior teachers graciously helped me to expound on and integrate.

At the Asian Institute of Management, I conceptualized anticorruption workshops for SMEs (small and medium enterprises). With a lot of help from my more experienced teammates, I learned how to reconcile the different temperaments of workshop attendees and convince them to participate in group dynamics, the intricacies of connecting and forming partnerships with stakeholders, and how to compensate for unforeseen complications that could derail major events.

At the Commission on Higher Education, colleagues taught me to comprehend memorandum orders, analyze innovation and development proposals, and sift through seas of data to aggregate much-needed figures. I am fortunate that in every workplace, there have always been helping hands willing to share knowledge and skills, much like how worker bees share resource coordinates with the rest of the colony. For me, the melding of minds toward a singular objective is the precursor to the success of an endeavor.

Nowadays, in an uncertain atmosphere fueled by doubt, speculation, and divisiveness, I take comfort in the thought that, like bees, the Filipino people will eventually hearken to a “waggle-dance” that can rejuvenate, or better yet, unite our fractured society. Perhaps the key is in the simple act of sharing, of being gracious and generous—positive values forgotten but not lost in the maelstrom of unrest. The melding of minds allowed me to grow as a professional. I am confident that the melding of minds will help the Philippines ripen as a nation.

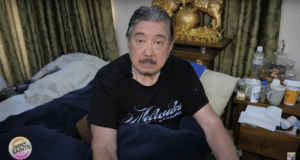

Raymundo V. Lucero Jr. is a senior monitoring and evaluation officer for the K-to-12 Transition Project Management Unit of the Commission on Higher Education.