Can Duterte ‘populism’ bring lasting peace, development?

SELFIES WITH DIGONG President Duterte gamely joins in selfies with participants of a feast celebrating the end of Ramadan in Davao City. MALACAÑANG PHOTO

The spectacular victory of Rodrigo Duterte in the 2016 presidential election reflects both a global surge in populist politics and the latest wave in a sea change in the Philippines.

Globally, populism has emerged across the traditional left-right spectrum, both in bids to capture power in established political parties and to champion nontraditional political organizations in challenges to existing power constellations. Where is President Duterte situated?

In part, his campaign echoed the new rightist populism of Donald Trump in the United States, the “Brexit” campaigners in the United Kingdom and right wing movements in France and Germany, which appeal to the “lowest common denominator” in society—

people’s fears and religious, ethnic and gender prejudices.

But Mr. Duterte also ran with a promise to bring peace and positive purpose to the state, echoing the left political populism of Bernie Sanders in the United States or Jeremy Corbyn in the United Kingdom, appealing to people’s idealism and hopes for a fairer and more equitable politics.

Hopeful signs, virulent form

Since taking office, his record is mixed: release of leading communist party prisoners, the revival of peace talks in Oslo, Norway, and positive signals on agrarian reform. These are hopeful signs, but the spate of extrajudicial killings and a denunciation of the United Nations for criticizing the killings signal a more virulent form of populism.

Populists across the spectrum have either sought to win the leadership of long-established political parties or to champion nontraditional political organizations in a bid to capture government. Mr. Duterte’s stance is ambiguous here, too.

He ran as the stalwart of a moribund Partido Demokratiko Pilipino-Lakas ng Bayan (PDP-Laban) and relied on traditional clan networks in Mindanao and the Visayas. However, he claims to represent the poor and has brought dissidents and provincial interests into his Cabinet.

Direction of change

This raises key questions about the direction of change.

What accounts for the rise of populism in general and in the Philippines in particular?

What will determine whether the President’s populist administration is likely to bring peace and law and order to the land as he has promised?

How should people assess the President’s plan to change the Constitution and introduce federalism?

How might constitutional change affect peace?

Is constitutional change likely to bring a step change in Philippine economic development?

Populism in PH

What unites all strands of populism today is the ability of leaders to directly appeal to voters above the heads of traditional political intermediaries, permitted both by changes in information technology and rapid urbanization.

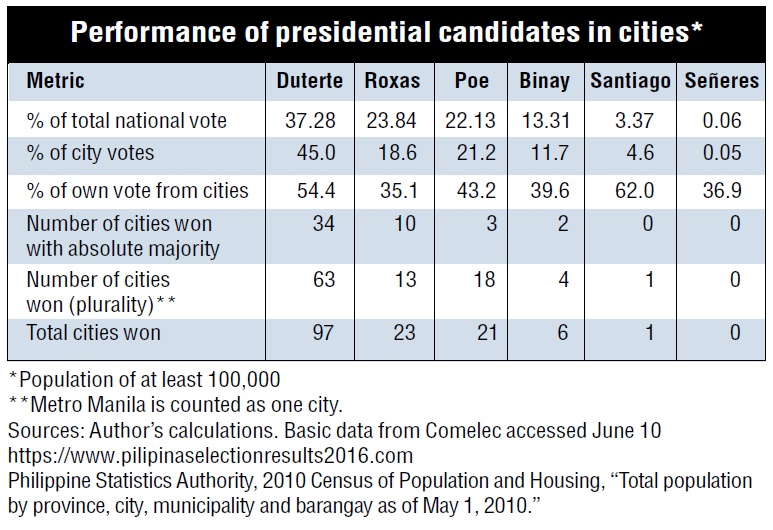

In the Philippines, the number of mobile phones has soared from 3.7 per 100 people in 1999 to more than one phone per person today. By the 2016 elections, some 45 percent of votes were cast in cities with a population of 100,000 or more people.

Technological and demographic changes have opened the terrain for politicians to reach beyond traditional networks to connect directly with voters.

In the Philippines, politics has long been dominated by shifting “clan networks and alliances,” rather than programmatic political parties. This was true even in the heyday of the Nacionalistas and Liberal Party before then President Ferdinand Marcos’ martial law.

After formal democracy was restored in 1986, there was plenty of evidence of political dynasties asserting themselves despite “antidynasty” provisions in the 1987 Constitution.

However, in the early 1990s there were signs that a new populist practice, layered on clan politics, was emerging with urbanization, expansion of access to mass media and the resultant weakening of ties of family, region and language group. Populist appeals for votes dominated the presidential campaigns of Miriam Defensor Santiago and Joseph Estrada in the 1990s.

For more than two decades, the secret to contesting national elections in the Philippines has been to pursue a two-track course—winning over clan alliances while reaching into the urban population.

Crime-busting strongman

Throughout his career, Mr. Duterte has managed to combine the spectacle and techniques of populist politics with a magisterial command of clan politics to create a political dynasty in Davao City and gain national prominence as a “crime-busting” “strongman.” This was the base from which he launched his bid for the presidency.

Examining the election results in the table below, it is clear that Mr. Duterte won by dominating the cities. He won the vote in Metro Manila and in another 96 of the 148 large cities and municipalities. More than 54 percent of his own vote came from these cities.

Populism resonates most effectively in the cities where traditional clan networks are less important and most people are connected to the internet.

Social media

It is clear that social media played a decisive role in Mr. Duterte’s victory like in all the populist surges in politics around the world today. This is because candidates can reach ordinary people without passing through political party hierarchies or winning favor from established media.

This is not to say that clan politics is no longer important. There were clear regional vote banks for each of the presidential candidates. Mr. Duterte won most of the Mindanao and central Visayan regions and he came from an old political family and counted on Cebuano elite support. It was the combination of a strong regional base with his big win in the cities that led to his victory.

Populist appeals have the most force when people feel alienated and angry about established politics. This is how neoliberalism has affected politics today. Even where there is economic growth, income inequality has risen to outrageous proportions with the deregulation of markets.

People’s anger

Nowhere is the perception of inequality starker than in urban areas. While left populism (Sanders, Corbyn and Spain’s Podemos) taps into people’s anger by appealing to their sense of social justice and calling for the regulation of capitalism, right populism appeals to people’s fears and prejudices.

In the United States, Trump targeted “Mexican rapists” and Muslims, while the Brexiters and Marie Le Pen point the finger at immigrants and Muslims.

Mr. Duterte pointed to the drug pushers and users, who people fear are destroying their communities. He presented himself as an “outsider” fighting the “Manila establishment” and ineffective central government.

Closer to ‘dark side’

The President’s encouragement of vigilante action, his statements on women and his warnings to Congress and the media place him, so far, closer to the “dark side” than the light in the populist divide.

Populists often cross the divide between left and right in any case. They play loose with established law and woo the population to simplistic solutions to complex problems. More often than not, populists fall as sharply and as quickly as they emerged—witness the fate of Alberto Fujimori in Peru.

During research conducted over a decade on “crisis states” at the London School of Economics, we have concluded that the most important factor in achieving “state resilience,” or lasting peace, is the consolidation of basic security, in which the state’s armed forces and police have a functioning chain of command, and can contain and marginalize all nonstate armed actors, without unleashing repression to maintain power.

While the Philippine state has contained major armed challengers, it has not managed to defeat them and the landscape is still strewn with nonstate armed actors, which security forces seem unable to disperse and at times rely on to maintain order.

Paramilitary actors

Mr. Duterte himself, as mayor of Davao, relied on paramilitary actors to “cleanse” the city. Although his success in reducing crime and violence within city boundaries was heralded by local citizens, it is doubtful that this is a sustainable way to secure lasting peace.

The proliferation of weapons in nonstate hands is extensive. Governors and mayors (not to mention powerful families and corporations) forge their own relationships with officers of the Armed Forces of the Philippines and the Philippine National Police, do deals with nonstate armed groups like the New People’s Army and mobilize their own paramilitary groups.

Principal drivers of violence

Mindanao Database of International Alert has provided plenty of evidence that the principal drivers of violence in Mindanao are disputes between clans and revenge killings, over positioning in and control of economic rents, profits and assets in the informal economy.

The President may score victories in his fight against drug syndicates and in peace talks, but such gains are unlikely to outlast his presidency if he does not ensure a step change in establishing the preeminence and professionalism of state security forces.

If he relies on paramilitary forces to achieve quick wins, as he did in Davao City, he may well perpetuate this foremost fissure of fragility in the state.

Proposals to change the Constitution and introduce federalism may only strengthen regional power brokers and weaken possibilities to formalize economic activity and bring it under the regulatory authority of the state. A shift to federalism might also make delivery on any peace agreements impossible.

Transformative development

How likely is it that the President can use his office and popular support to transform the reigning “political settlement”—the distribution of power in society and the economy—in ways that promote more transformative development?

This requires a radical change in patterns of investment, not only through building new infrastructure in sustainable energy and transportation, but also in industrial and agricultural processes that would allow the country to climb global value chains.

Such a change would affect the domestic balance of economic interests and the positioning of the Philippines in the global economy.

The President’s commitment to maintain the previous administration’s economic policies makes major change less likely.

While he has given control over prominent departments of the executive to the left, these are “soft” agencies unlikely to have an impact on structural change.

Achieving the type of structural change required to launch the country on a developmental trajectory necessitates a time horizon longer than the six-year presidential term.

The populist character of the Duterte presidency may compel him to respond to the social claims made on the state by the poor and the organizations that helped to win his election, or by communist and Bangsamoro organizations in exchange for peace, thus diverting resources to immediate poverty relief and buying off dissident movements rather than structural change.

To keep elites on board may require other payoffs. A move to federalism through constitutional change, in the absence of a much stronger central state, would likely dissipate developmental resources even further.

Dreaming in color

Three possibilities would appear more promising.

First, the President could abandon strongman rule and vigilante violence and use his popularity and the power of his office to build a disciplined political party, perhaps based on a reinvented PDP-Laban, which can outlast his presidency and continue to promote a developmental policy program.

Second, the President could use talks with the Bangsamoro and communist movements to forge peace that is built on a plan for long-term structural change and give their best cadre a major role in the process.

Finally, Mr. Duterte could leverage his popular support to win over public opinion to shifting the country from its overreliance on the United States and engaging China constructively over joint development of the South China Sea, investments in Philippine infrastructure and in a renaissance of manufacturing.

Perhaps, this is dreaming in color, but that is what should be done at the start of a new presidency.

(James Putzel [DPhil Oxford] is professor of Development Studies in the Department of International Development at the London School of Economics. Between 2000 and 2011 he was director of the Crisis States Research Centre. He is known in the country for his book “A Captive Land: The Politics of Agrarian Reform in the Philippines” and he continues to work on land issues, notably in China. His recent research has focused on politics, economic development and problems of “state fragility” in a wide range of countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America.)