DIN Javellana’s world crumbled when dengue struck his son. “My son had recurring fever for three days and the antipyretic was not taking effect. We decided to bring him to the hospital and the lab test results showed he had dengue.”

Javellana was anxious as she had heard so many horrible stories about patients suffering from dengue-like bleeding and going into shock and worst, even death. As she saw her son very weak and helpless, she kept telling her husband “I wished it were me instead.”

Traumatic

It was an ordeal that she had to go through but fortunately, the intervention proved timely and her son went home after seven days of confinement. “That whole experience was traumatic and I wouldn’t want that to happen to any family,” she said.

Dengue cases rose 23 percent to 66,299 between Jan. 1 and July 16 from 53,938 in the same period last year, according to the DOH Epidemiology Bureau.

Fatalities

Many of the cases were in Calabarzon with 8,059 (12.2 percent); Northern Mindanao, 6,447 (9.7 percent); Central Visayas, 6,422 (9.7 percent); Soccsksargen, 6,063 (9.1 percent); and Central Luzon, 6,048 (9.1 percent). Furthermore, the number of deaths was higher—287 compared with 186 in the same period in 2015.

Dengue viruses are arboviruses (arthropod-borne virus) that are transmitted primarily to humans through the bite of an infected day-biting, female Aedes species mosquito. With the onset of the rainy season, authorities are again urging the public to eliminate the dank and dark places around our homes and immediate environs where mosquitoes tend to breed.

Unable to stop rise

Such efforts at vector control have not been able to put a stop to the rising dengue cases in the country despite the incessant efforts by government authorities as well as private initiatives to prevent the spread of the disease.

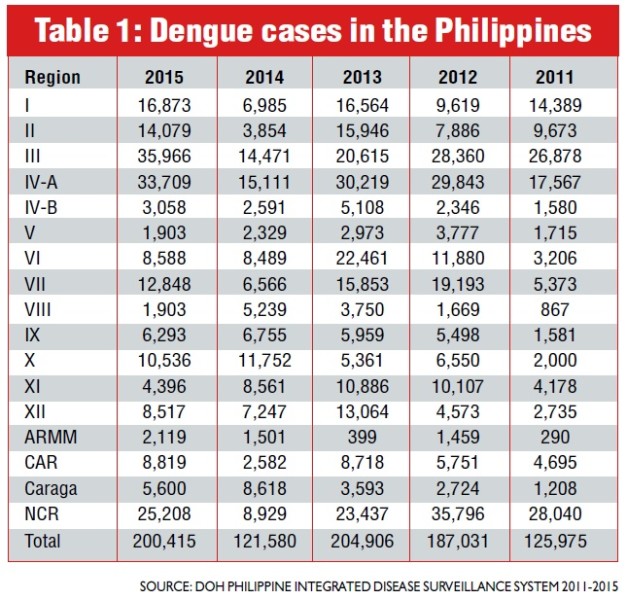

Consider the DOH data on how dengue has grown in terms of numbers of infected Filipinos. Table 1 shows that despite efforts to clean up our communities and stop the spread of mosquitoes in all regions of the country, dengue cases have increased over the past five years.

Table 1: Dengue Cases in the Philippines (Source: DOH Philippine Integrated Disease Surveillance System 2011-2015)

Worldwide concern

The Philippines, if it is of any consolation, is not alone in this situation. Dengue has become a worldwide concern and is particularly on the rise in our region. Almost 75 percent of the global population exposed to dengue lives in the Asia-Pacific region where 1.3 billion people are at risk, according to reports.

The data paint a grim picture as dengue is a leading cause of hospitalization in children in the region. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), there has been an overall expansion of dengue in Southeast Asia over the past decade.

Severe dengue is endemic in most Southeast Asian countries, with rates of severe dengue being 18 times higher in the area compared with the Americas. Cambodia, the Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore and Vietnam carry the biggest dengue burden, according to the WHO.

The number of reported cases increased in each of these nations over the past 10 years and all four serotypes cocirculate. Behind these numbers are the countless suffering that dengue has brought families across the land. In the Philippines, the death toll was 598 in 2015, 465 in 2014, 660 in 2013, 921 in 2012 and 654 in 2011.

The traditional approach to combat the spread of dengue has relied mainly on vector control—getting rid of the mosquito breeding sites and self-protection. But the number of those getting infected are still rising so it is important that everyone has to take extra measures to get immediate medical help if dengue strikes.

No known cure

There is no known cure for dengue but lives can be saved with early detection and optimal management. One must observe closely for any of the possible symptoms if they occur. (See list.)

Dengue has been on the top agenda of the national government since 1993 when the DOH initiated the National Dengue Prevention and Control Program, with Region VII and Metro Manila serving as the pilot sites.

It was not until 1998 when the program was implemented nationwide. The targets of the program are the general population, local government units and local health workers.

Integrated approach

Overall, the vision is to create a “Dengue Risk-Free Philippines” with the goal of improving the quality of health of Filipinos by adopting an integrated approach in the prevention and control of dengue infection by reducing morbidity and mortality from dengue infection, and preventing the transmission of the virus to humans.

Part of the program is the establishment of Dengue Reference Laboratories in regional hospitals to increase the number of government hospitals with laboratories capable of performing dengue diagnostic tests, and to ensure surveillance and investigation of all epidemics.

A breakthrough was achieved in 2015 in the global fight against dengue when the first dengue vaccine was produced by a French pharmaceutical company. The first documented cases of dengue fever were in Cairo (1799), Indonesia (1799), Philadelphia (1780) and India (1780).

Four serotypes

Scientists have long been stumped by dengue, which has four serotypes. Clinical trials on dengue vaccine carried out on over 40,000 people from 15 countries have found that it can reduce dengue fever due to all four serotypes and prevent 8 out of every 10 hospitalizations, and reduce up to 93 percent of severe dengue cases.

Trials were conducted in Asia and Latin America in five endemic countries. Three injections were administered six months apart in 2- to 14-year-old children in the Asia trial and 9- to 16-year-old children and adolescents in the Latin America trial.

Hope

The development and deployment of the dengue vaccine would be a great aid for health practitioners, especially for those who have managed dengue patients and have seen its debilitating impact on people. I see the new vaccine as providing hope to our people that finally, we have the means to combat this health threat.

Many of us are familiar or have personally been involved in the campaign to rid our surroundings of mosquito-breeding places or what we also call vector-control measures and have realized that this is not enough.

Year-round threat

Hopefully, this new vaccine together with other government and private-sector activities against dengue will prevent the disease. There is no specific season for dengue as it can infect year-round. Hence, even after the rainy season, we all must remain vigilant.

In terms of prevalence, if we talk about 10 countries around the globe, we are at No. 4. So just considering that we are among the worst affected makes it more urgent for us to take action and implement a preventive program among the most vulnerable sectors of our population.

Highest infection rate

The Philippines had the highest dengue infection rate in the Western Pacific region from 2013 to 2015, according to the DOH.

The implementation of the vaccination program is a vital part of achieving the WHO goal of reducing dengue mortality by at least 50 percent and dengue morbidity by at least 25 percent by 2020.

The DOH has recently launched its school-based immunization program against Dengue in three regions: Central Luzon, Calabarzon and Metro Manila. Their program covers all Grade 4 pupils, 9 years old and above.

Surveillance

The children will be monitored through a surveillance monitoring to be conducted by the DOH Epidemiology Bureau and the Philippine Children’s Medical Center, a tertiary training hospital under the DOH.

Some have raised the issue that the vaccine is only 65-percent effective against dengue. But even if they are correct for the sake of argument that percentage alone would make a substantive contribution to fighting the spread of the virus among our communities. And this is for a disease that as of today has no known cure.

Reducing severity

Likewise, getting the majority of the people out of dengue’s threat would reduce the source of the disease, therefore lessening the chances of transmission as the vaccinated individuals will not become the source of infection in case they are bitten by mosquitoes.

On top of it all, vaccination can reduce the severe form of dengue that can lead to hospitalization, proving the adage that “An ounce of prevention is better than a pound of cure”—reducing absenteeism in school and workplace, loss of productivity, family expenses and the emotional burden on the victims and their loved ones.

(Dr. Rose Capeding is a pediatric infectious disease specialist of the Research Institute for Tropical Medicine, and Asian Hospital and Medical Center. She has conducted epidemiological and vaccine studies on dengue.)