IN RESPONSE to a question raised during one of his press conferences in June about the killing of journalists, then President-elect Rodrigo Duterte echoed a recurring narrative in the public mind: the belief that journalists are killed because they are corrupt. He went on to describe how a broadcaster in Davao had been abusive and provoked his own murder.

The observation struck a responsive chord among many who were quick to urge the media to get their act together and do something about the scoundrels in their ranks. The fiction has been fixed for many as truth—that those engaged in corrupt practices are the only ones endangered. In Duterte’s words, “You won’t be killed if you did nothing wrong.”

Failings of society

The truth, however, is more complex than this simple dismissal would make it appear. The practice of journalism in the country reflects the failures and failings of the rest of society. While the market for news lavishes impressive rewards on the media elite, a great many media workers struggle to earn a decent income.

In the provinces, radio and TV stations sell airtime to blocktimers without holding them accountable for the commentaries they deliver. Indeed, a taxonomy of terms—AC-DC (attack-collect, defend-collect), ATM (bribery)—describes the corruption that afflicts the news business.

Doing their duty

But even this troubled terrain has grown enough journalists who do their duty, doggedly keeping alive a conversation about public issues and concerns, and protecting news media as a pillar of democracy. Unlike their more fortunate colleagues in the capital, these journalists work under greater stress and are more vulnerable to violence.

The stories of those who died because they were simply doing their duty might help to fix the narrative and get us closer to the truth. To tarnish their memory by assuming they were corrupt does them a gross injustice. And given his stand on corruption and his defense of the underdog, had he been aware of their cases President Duterte might have supported these victims.

Malacañang’s condemnation of the most recent attempt to kill a journalist—the wounding of Surigao City broadcaster Saturnino Estanio and his son—and the organization of a task force on the killings that the Palace announced on July 2 suggest renewed appreciation of the extent of the problem. Hopefully, the investigation into the killings will also help establish how most of the slain journalists were doing their part in the difficult and dangerous task of reforming Philippine society.

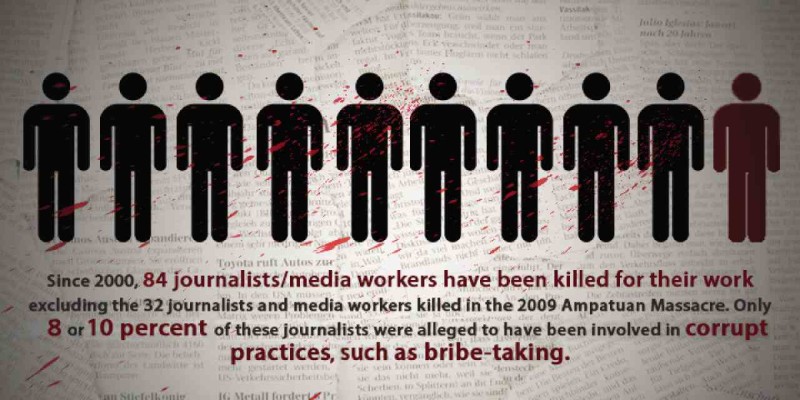

Since 1986, the Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility (CMFR) has documented 152 work-related cases of journalists being killed. Fifty-one cases involved reporters and broadcasters exposing graft and corruption. Since 2000, only in eight cases were there allegations about the involvement of the victims in corruption. No such allegations mar the rest of the cases. (See infographics.)

Crusading journalists

“The newspaper business is hazardous to health,” the Supreme Court once said, referring to the 1991 murder of Nesino Paulin Toling, a newspaper publisher and editor in Ozamiz City, Misamis Occidental. Toling and his wife published a weekly from their office, without a car, phone or computer. Reporting his case in the Los Angeles Times, Bob Drogin wrote about the couple’s commitment.

Toling’s wife, Virgie, would take “a three-hour boat and bus trip to the nearest printer. Three days later, she (would pack) the 3,500 issues and (carry) them back home.” Sometimes they covered their costs. But as Virgie said, “the newspaper was his (Nesino’s) dream.”

On April 14, 1991, a man walked into the office of the Panguil Bay Monitor and shot Toling. The paper could have offended any number of the targets of the paper’s scathing exposés of graft and corruption, including cases of government and uniformed officials being connected to illegal logging and the drug trade. The gunman was convicted for the murder. But no mastermind was ever identified.

Reporting politics and governance is an indivisible part of Philippine journalism’s responsibilities. Many journalists and broadcast anchors have even taken up good governance and anticorruption advocacies for which they have earned the ire of both local and national officials and politicians.

In February 1996, Ferdinand Reyes, of Dipolog City, Zamboanga del Norte, was killed in front of his 3-year-old daughter while inside the office of the newspaper Press Freedom, which he published. Reyes, also a human rights lawyer, was in his office after a hearing at the local Hall of Justice. The gunman, posing as a client, was allowed entry and shot Reyes.

As publisher and editor, Reyes was known for criticizing abuses by the military and by corrupt government officials. He left behind several stories, including reports on smuggling, and another on election campaign expenditures.

In Pagadian City, Zamboanga del Sur, Edgar Damalerio held several jobs. He was a radio commentator for dxKP, managing editor of the Zamboanga Scribe and host of the cable TV program “Enkwentro” (Encounter). He detailed the involvement of local officials, police and military men, and even his fellow journalists in anomalous government transactions and illegal activities. He filed cases against officials for wrongdoing, including the allegedly anomalous purchase by the Pagadian City government of six passenger “jeepneys” (mini buses).

On May 13, 2002, Damalerio was driving from a press conference when he was shot by two men on a motorcycle. His companions—Edgar Amoro and Edgar Ongue—got a good look at the killer, whom they later identified as Guillermo Wapile, a local policeman.

Philip Agustin had returned to Dingalan town, Aurora province, to distribute copies of a special edition of his newspaper Starline Times Recorder when he was killed on May 10, 2005.

The special edition reprinted reports about the mismanagement of funds for the rehabilitation of the town, which had been damaged by flash floods and landslides. The alleged mastermind, Mayor Jaime Ylarde, was prosecuted but the case was dismissed in 2008.

Reporting criminal activities

CMFR has documented 29 cases of journalists killed for reporting on criminal activities involving both private individuals and public officials in their localities.

Rolando Ureta had been receiving death threats since August 2000. He was campaigning against drugs and corruption in Aklan through his radio program on dyKR.

On Jan. 3, 2001, two men on motorcycles trailed Ureta while he was on his way home from his evening broadcast. He was shot three times by the assailant but managed to run to a house along the road where he succumbed to his wounds.

Scam in electric firm

Journalists have also probed and commented on corruption in the private sector. Roger Mariano was at the point of breaking a major story about a scam in a local electric company in Ilocos Norte when he was killed on July 31, 2004.

Gunmen ambushed Mariano while he was on his way home from his program at radio station dzJC. Mariano’s belt bag contained a disk with information on the alleged scams in a local electric company. The police failed to recover it at the crime scene.

In Palawan, Fernando “Dong” Batul’s commentaries angered powerful people in his province. At the end of his radio program, Batul would say in Filipino that “Journalists must fight what’s wrong and fight for what’s right.” He was murdered on May 22, 2006.

The alleged gunman, former police officer Aaron Golifardo, was among the objects of his commentary. Batul also deplored media corruption, frequently warning against the practice of “AC-DC.”

Advocates as journalists

Stumbling upon documents proving the misappropriation and mismanagement of funds at the regional office of the Department of Agriculture (DA) in Region XII, Marlene Esperat, then a chemist for the department, began her crusade against erring officials.

The results of her investigation she published in her column in the Midland Review and aired in her radio program.

Esperat’s exposés eventually led to the investigation of the P728-million fertilizer fund scam in the DA. She also reported on the nonremittance of Government Service Insurance System payments for DA Region XII employees.

Esperat also filed administrative suits against DA officials as high up as undersecretaries, including Jocelyn “Jocjoc” Bolante.

On March 24, 2005, a gunman walked into her home in Tacurong City, Sultan Kudarat province, while she and her children were having dinner. The gunman greeted Esperat and then shot her several times.

Malampaya gas

The case of Gerardo Ortega also involved an advocacy. Since the start of his program in dwAR in 2009, Ortega had been receiving anonymous death threats. An environmental activist, Ortega accused the mining companies of destroying the environment. He supported a petition in the Supreme Court in behalf of Palaweños to invalidate a revenue-sharing agreement on the Malampaya natural gas project in Palawan between the local and national governments.

On Jan. 24, 2011, Ortega was shot inside a used clothing store on the national highway in Puerto Princesa City. The gunman and his accomplice confessed that they had been paid P150,000 to silence Ortega. A former governor of Palawan is on trial for allegedly masterminding his murder.

Impunity, press freedom

The killing of journalists and media workers is an indictment of the weakness of the rule of law in the Philippines. Out of the 152 work-related cases recorded from 1986, only in 16 cases have gunmen and their accomplices been convicted. Other cases have not progressed due to a lack of evidence or the failure to arrest the suspects.

Public indifference constrains efforts to end impunity, the failure to punish wrongdoers. Many believe that only corrupt journalists are killed. This fiction must be revised. Corruption involves other partners—powerful individuals with the means to corrupt. The specifics are more complex and more nuanced than blanket explanations of why journalists are killed would make us believe.