From Noy to Rody, nation in between

As President Aquino completes his six-year term and incoming President Rodrigo Duterte begins his, this article looks into their respective brands of leadership through the lens of international relations theories, explaining how their belief systems translate to policies and pronouncements that will define their presidencies.

TWO WEEKS ago, outgoing President Aquino admitted that he toyed with the idea of imposing martial law in Sulu to allow state security forces to go after Abu Sayyaf bandits.

Article continues after this advertisementBut in deciding against it, he said: “There’s no guarantee that there would be positive results. There might even be negative results. It might win more sympathy for the enemy.”

With these three sentences spoken in the final days of his term, Mr. Aquino demonstrated that his liberal thinking often outweighed the moments he entertained a realist approach.

Dogma of liberalism

The President’s almost predictably consensus approach to resolving internal security reflects the Kantian dogma of liberalism, emphasizing on the impact of behavior and the protection of people from excessive state regulation.

It is a paradigm that assumes the application of reason in paving a way for a more orderly, just and cooperative world, restraining disorder that can be policed by institutional reforms.

Parents’ influence

As Chief Executive and Commander in Chief, Mr. Aquino has described himself as a leader who seeks consensus, espousing a largely liberal thinking that almost certainly was the influence of his parents—democracy icons Ninoy and Cory Aquino.

In dealing with the overlapping claims in the South China Sea, the President’s state of mind urges him to champion a rules-based approach under the facets of idealism, magnifying moral value and virtue by asserting that our sovereign state and its citizens should be treated as ends rather than means.

The moral ascendancy the Philippines has gained from the arbitration case proves the centrality of a collective power.

Building alliances

Building alliances with other nations, Mr. Aquino recognized that while his administration pushed for the modernization of the Armed Forces of the Philippines, it remains one of the weakest in Asia after decades of neglect.

Mr. Aquino’s economic reforms can be construed by the principles empowered by neoliberals. The currency of economic liberalization, international trade, cross-border capital flows and regional integration somehow flirts with the language of increased investment, technology transfer, innovation and responsiveness to consumer demand that was achieved during his term.

By the time he steps down from office, the Philippines has become Asia’s rising star.

Concern for others

The social services pushed by the Aquino administration reflected liberal thinking adhered to by the outgoing President. The vision of widening equitability among the Filipino people in the hope of unleashing the fundamental human concern for others’ welfare makes progress feasible.

While naysayers of the paradigm agree that our world is anarchic and state interests are fundamental for survival, still, security reforms can be inspired by a compassionate ethical concern for the welfare of the people.

Whole-of-nation approach

As commander in chief, Mr. Aquino adopted the “whole-of-nation approach”—in which government and communities work together—to address the communist insurgency.

Notably, he defied protocol and met with rebel chief Murad Ebrahim to jumpstart the stalled peace negotiations with the Moro Islamic Liberation Front.

The self-sacrificing act a leader may embody naturally coincides with the Kantian behavior of peaceful, consultative and cooperative virtues of Mr. Aquino.

He also showed belief in the justice system by hauling erring public officials to court, but ironically, he appeared to have undermined the judiciary at times.

He spearheaded the impeachment of the late Chief Justice Renato Corona, viewing the appointee of former President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo as a possible obstacle to his campaign to make the Arroyo administration accountable for its alleged corruption.

Mr. Aquino also openly criticized Supreme Court decisions that he felt impaired his own governance.

However, his appointment of Ma. Lourdes Sereno as Corona’s successor was trailblazing for all intents and purposes for she will sit as Chief Justice for two decades.

Wendtian tendencies

Nonetheless, this can also be overshadowed by Mr. Aquino’s Wendtian tendencies to construct his own choices by relying too much on plausible stories without actual tests on anecdotal evidence.

For example, when the people, whom he famously called his “bosses,” wanted him to sack government officials for their ineptitude, he defended his men, pushing many of his supporters in 2010 to abandon him by midterm.

And even until the last months of his presidency, Mr. Aquino heaped blame on his predecessor for the country’s woes, which has become a turnoff for many.

At noon of June 30, Mr. Aquino hands over the country’s reins to incoming President Rodrigo Duterte. With it comes a change in styles of governance and belief systems.

Similarities

Indeed, the two Presidents share similarities: their devotion to their mothers, closeness and loyalty to friends, aversion to unsolicited advice and the ability to command an army of staunch believers.

They both walk the talk, albeit taking different approaches.

As the country embarks on a new journey in our transformative process as a young nation-state previously ruled by a dictator, a housewife, a general, an actor and two subsequent economist Presidents in contemporary period, the Philippines has yet to morph into an economic and military power in the region.

Now that a new driver takes the front seat of the presidency in the country’s roller coaster ride through democracy, is the country ready for another shift from a liberal to a realist?

The just concluded national elections have brought us to the smoothest transition we have seen in recent history.

Return of oligarchy

The narratives in Philippine contemporary period saw the effects of ironclad dictatorship and cronyism but also the return of oligarchy in a softhearted leadership.

People power uprising paved the way for unseating corrupt leaders but also installed successors who fell short of expectations.

The selective forgiving culture inherent in Filipinos has resulted in a people power fatigue.

Our contemporary Presidents’ rule mirrored the kind of leadership and reactive political culture we mustered during their respective terms.

Machiavellian realist rule

But six administrations of ups and downs—from martial law to the restoration of an immature democracy in the Philippines—gave us a picture of a Machiavellian realist rule and Kantian altruistic ideals.

After more than three decades of seeking the right kind of leader—mixing realist-, liberal- and constructivist-thinking Presidents from Marcos to the second Aquino—coming up with the best formula to make our country more secure and progressive remains elusive.

Now comes Mr. Duterte.

Campaigning for the presidency, the 71-year-old grandfather said he wanted to use Army Rangers to help the police force crackdown on drug syndicates, and then upon his election, announced he wanted armed civilian auxiliaries to take on the drug menace at the barangay level.

His draconian measures are hugely popular in Davao City, where he ruled as mayor for decades. People justified their allegiance to him and his ways by claiming they felt safe and such security made their businesses and livelihood thrive.

He has pledged to replicate his ruthless methods to eradicate criminality nationwide while his aides have backtracked on his campaign promise to do so in three to six months.

Death to criminals

A week before his inauguration, Mr. Duterte said that death to criminals was not deterrence to crime. It was retribution.

The thought of brutality in exchange for security has become a cause for great concern for human rights advocates.

Exuding power

This Hobbesian tradition of exuding power can best exemplify the type of governance that the incoming administration may possess.

The struggle to pursue consolidated national interests amid the country’s internal and external insecurities could result in realist-leaning statecraft for the administration to survive in a hostile environment.

The realist paradigm assumes that states are rational actors playing in their national interest.

Given the humongous responsibility bestowed upon Mr. Duterte, as he incessantly advocated restoring peace and order, presumed to lead to progress and development, his game plan would strongly resonate with his philosophical and ethical consideration.

The action is neither good nor bad as long as it will pave the way for the pursuit of his national self-interest.

Among other things, Mr. Duterte has promised to push for federalism, the restoration of the death penalty, peace with communist rebels and the passage of the freedom of information bill. Ironically, he declared he would use only state-run media, thus undermining the country’s free press.

Alliance with Marcos Jr.

Most alarming to those who fought for democracy three decades ago is Mr. Duterte’s alliance with losing vice presidential candidate Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr., promising the latter a Cabinet position by next year and the burial of his father, the dictator Ferdinand Marcos, at the Libingan ng mga Bayani.

The incoming Cabinet is a hodgepodge of personalities from the Right and the Left to industry leaders and relative unknowns.

So far, only Mr. Duterte’s economic team brings some confidence to the rest of the nation that has now become an outsider in the former city mayor’s clique.

His security cluster is not exactly a formidable team for the heightened tensions in the Asia-Pacific region.

He himself has shown disdain for regional and international cooperation, judging by the remarks he made in his infamous postelection press conferences.

Beyond his being antiestablishment, Mr. Duterte was not to be disturbed from his slumber during the early morning Independence Day rites on June 12, raising the question whether traditions that make a nation might even be disregarded in the next six years.

Waltzian neorealism

The parsimonious and enduring persona the incoming President tries to paint before the people, whether consciously or unconsciously, is an astute personification of Waltzian neorealism.

This favors a systemic approach that asserts pragmatic, realistic and actual execution of relative power in a similar rational manner with outcomes falling within the expected range to ensure the leader’s own survival and that of the state he will be ruling.

Different styles

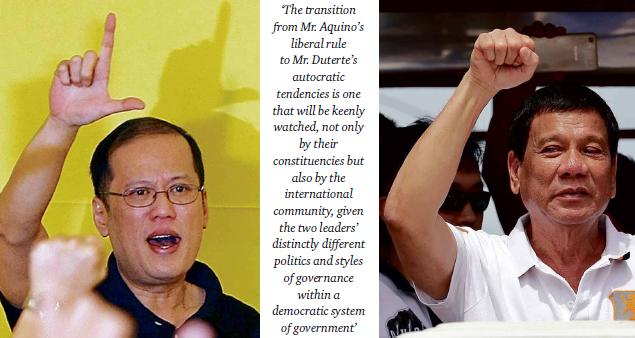

The transition from Mr. Aquino’s liberal rule to Mr. Duterte’s autocratic tendencies is one that will be keenly watched, not only by their constituencies but also by the international community, given the two leaders’ distinctly different politics and styles of governance within a democratic system of government.

Both campaigned on a platform of change—the single, most powerful word in any Philippine election.

But whether it is a collective change or personal change, personal interest or national interest, is something only the Filipino electorate can answer and define.

(Nikko Dizon is a defense and political reporter of the Inquirer. She holds a master’s degree in National Security Administration from the National Defense College of the Philippines (NDCP). Cabalza teaches national security administration at the NDCP and political anthropology at the University of the Philippines Diliman.)

RELATED STORIES

10 events that define President Aquino’s legacy