Stunting worsens despite GDP growth

The benefits of the country’s high gross domestic product (GDP) growth have eluded Angelita Salonga.

In February, the 28-year-old mother of five from one of the slums in Navotas City lost her youngest child due to complications from malnutrition brought about by a frequently empty belly and poor feeding habits.

Sickly

Her 3-year-old son Marso was so malnourished that he got very sickly. He suffered pneumonia, dehydration and later, sepsis. Cysts also sprouted in his lungs that made breathing difficult.

When the boy had to be brought to a health facility in nearby Tondo in Manila four months ago, doctors could no longer do anything but give him oxygen.

Scavenging

“They told me to wait for five minutes and if he still didn’t breathe, it means he’s gone. The truth is, it’s painful to lose a child. I did everything for him,” said the mother, who depends on scavenging for scraps to feed her children.

Salonga’s fate puts a spotlight on the country’s mounting problem of child hunger and malnutrition even as the economy grew stronger these past six years—the fastest in four decades—and the government continued to pour large sums of money into its conditional cash transfer program to reach more poor families.

Worst in 10 years

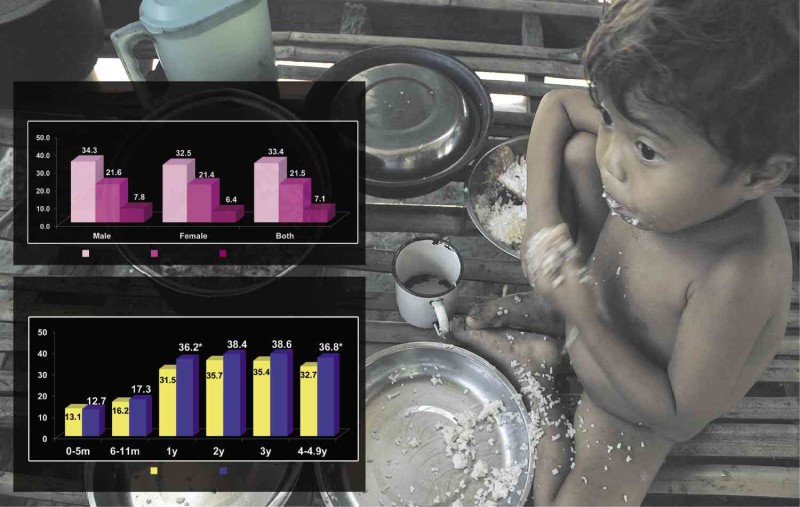

The latest National Nutrition Survey showed that overall malnutrition or stunting rate for Filipino children aged 0 to 2 was at its worst in the last 10 years at 26.2 percent in 2015—an indication that growth was not inclusive and that inequality between the rich and the poor continued to widen.

The 2015 data from the Food and Nutrition Research Institute (FNRI) also revealed that one in every two children in the poorest quintiles was stunted or whose height was below the World Health Organization (WHO) reference for his age.

The rate also jumped by almost three percentage points from 30.5 percent in 2013 among those under 5 years old.

High by global standards

“These figures are very high by global standards,” said Dr. Cecilia Santos-Acuin, FNRI chief science research specialist at a press conference in Manila in April, presenting the results of the latest data on the nutrition status of Filipino children.

“We need to emphasize on stunting because the Philippines failed this nutrition indicator for our Millennium Development Goals (MDG) in 2015,” said Acuin, noting that the country was among the biggest contributors to the global burden of hunger and malnutrition.

One of the country’s MDG target was to halve the number of stunted Filipino children to at least 22 percent and underweight children to at least 13 percent from the 1990 rates.

But current figures are still high, with the prevalence rate of children under 5 whose weights are below the normal or desirable standard for their age at 21.5 percent, increasing from 20 percent three years ago.

Feeding not enough

Acuin emphasized that while stunting, which is indicative of the level of chronic malnutrition, and being underweight remained a serious problem in the country, the former was a bigger challenge to tackle.

To make sure that children catch up with their appropriate weights, they must have regular access to the right amount and kind of food every day. But to solve stunting, feeding children will not be enough, Acuin said.

“There is emerging evidence now that you have to address the factors in a child’s environment, including the kind of care given to a child and his exposure to disease and infections,” she said.

Irreversible after 2 yrs old

Stunting, a condition largely irreversible after children reach two years old, is mostly due to inequality of access to nutritious food, lack of nutrition during the first 1,000 days of a child’s life and long periods of hunger.

Aside from leading to higher child mortality rates, stunting has many implications.

Putting up a competitive basketball team may be harder in the future while qualifying to be a pilot, policeman or a member of another profession where height is a requirement could become more difficult, Acuin said.

Lost opportunities

“When these children become adults and they continue to be stunted, there are many opportunities not available to them. They can’t apply for a job of a policeman. They can’t be pilots or apply in other jobs where height matters. You cannot dream of putting up a competitive Philippine basketball team if this is the state of undernutrition of our children,” she said.

Based on the survey, many of these stunted children are in the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao with a prevalence rate of 45.2 percent; Eastern Visayas, 41.7 percent; Mimaropa, 40.9 percent; the Bicol region, 40.2 percent; and Soccsksargen, 40 percent.

Stunting is also more rampant in rural areas and in the poorest households with a prevalence rate of 38.1 percent and 49.2 percent, respectively. The rates of underweight children in the poorest quintile is also four times more than in the country’s upper crust.

Acuin said the rise of stunting among Filipino children was brought about by several factors:

Food environment brought about by the effects of El Niño

Increasing incidence of illnesses among children

Poor breastfeeding and complementary feeding practices.

Only 50 percent of babies are exclusively breastfed during the first six months and only 25 percent continue to receive breast milk until 2 years old, according to Acuin.

Infant formula, breast milk

The study also showed that many babies were already given infant formula instead of breast milk when they reach

6 months old. By the time they are two, canned milk has become one of their largest sources of nutrition.

While exclusive breastfeeding among babies in their first 5 months is high at 52.3 percent (higher than infant formula feeding at 22.1 percent), its prevalence plunges to a dismal 5 percent when they reach 6 months old, data also showed.

At 6 months, formula-milk feeding with solid food among babies overtakes exclusive breastfeeding. Nearly 50 percent of infants receive formula milk when they turn a year old, according to the survey.

“Infant formula provides nutrition but does not protect children from illnesses. That is why we are seeing more stunting as they age … this is one reason why Filipino children are not growing optimally,” Acuin said.

The optimal growth of children, especially during the first two years of life, is also dictated by the kind of food that they eat and the frequency of food consumption.

But in the Philippines, only 3 in 20 children receive the minimum dietary diversity or nourishment from more than four food groups and less than 2 in every 10 receive an acceptable diet, according to the study.

Children in the Ilocos, northern Mindanao and central Visayas consume more varied meals consisting of more fruits and vegetables during the first two years of life than those elsewhere in the country.

Eastern and western Visayas and Zamboanga Peninsula have the lowest percentage of children aged 6 to 23 months who meet the minimum diet diversity.

But more children aged 0 to 23 months in the Ilocos, Cagayan Valley and northern Mindanao meet the minimum acceptable diet but at dismal rates of less than 11 percent.

“If there is no immediate intervention, we expect that malnutrition and stunting rates will continue to rise in 2016,” said Ned Olney, country director of Save the Children, an international children’s rights group.

Effective intervention

To help put a dent in malnutrition, Save the Children recently launched its Community-based Management of Acute Malnutrition project, a proven effective intervention in addressing severe hunger and acute malnutrition in Africa, at North Bay Boulevard in Navotas City.

The barangay, encompassing the 2-kilometer access road in the Navotas Fish Port Complex, was chosen as the pilot project area for registering the highest prevalence of wasting or low weight-for-height among children 0 to 59 months in the city.

Under the project, a first in Metro Manila, children with severe and moderate acute malnutrition will be treated and rehabilitated through timely detection and provision of treatment for those without medical complications. They will be provided with ready-to-use therapeutic food and other nutrient-dense food at home.

If implemented with precision, the project can prevent deaths of wasted children, the group said.

Challenge to Duterte

Olney underscored the importance of “sustained political will” and “increased nutrition investments” in the first 1,000 days of a child’s life for the country to achieve new global targets.

He enumerated the following recommendations that could help the new administration tackle child hunger and malnutrition:

Scale up cost-effective and affordable high-impact nutrition interventions, such as the promotion of exclusive breastfeeding, complementary feeding, vitamin A and iron supplementation, treatment of acute malnutrition and maternal nutrition, both at national and local levels.

Prioritize maternal nutrition in public and private health facilities since mothers need as much healthcare and nutrition as the child before, during and after childbirth to ensure the health and nutrition of infants and young children.

Strictly implement nutrition-specific interventions, such as infant and young child feeding, micronutrient supplementation and community-based management of acute malnutrition.

Protect and comply with the country’s Milk Code to prevent any attempts to revise and modify the law.

Address the status of community-based health and nutrition front liners, such as the barangay health workers and barangay nutrition scholars by implementing policies and mechanisms that can improve a highly politicized situation, and providing proper incentives and security of tenure, training and needed equipment.

Ensure that budget allocation for health and nutrition programs are sufficient, appropriate and prioritized.

Support the “First 1,000 Days Bill” to enhance the delivery of quality nutrition interventions in the first 1,000 days of life to prevent stunting among children.