Talking about ‘endo’

“ENDO” IS not just a shortcut for “end of contract,” a term applied to the time when short-term employment comes to an end (usually at five months). It is also the title of an indie movie about the love affair of a saleslady and a temporary worker who, like his employment status, is unsure and uncommitted, unwilling to submit to a long-term relationship and breaking the heart of the woman he loves.

The movie was released some years back, but I am surprised that the term “endo” has come back in fashion. As if labor groups, workers and presidential candidates only discovered the term now.

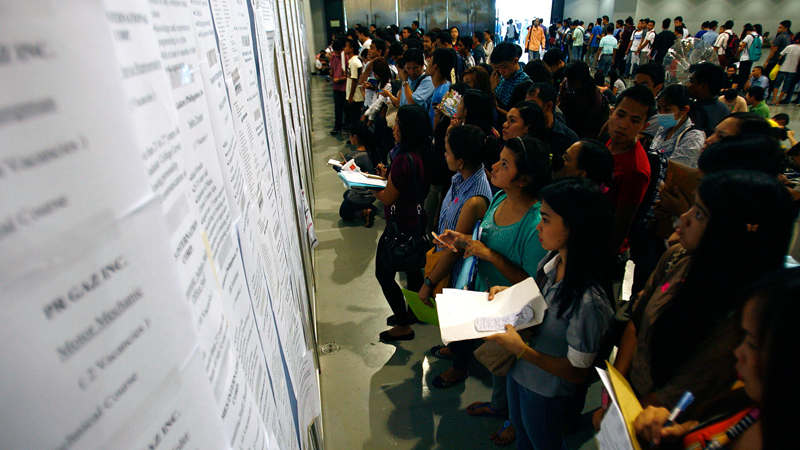

How long does it take before a practice and a policy becomes so firmly entrenched in society that a term for it is invented? That “endo” has emerged and become so popular that when presidential candidates mouthed the term at the last televised debate, almost all viewers knew what they were talking about, seems to me an indication of how common and, well, accepted the practice of contractualization has become.

Well, labor unions and even officials of the Department of Labor and Employment have not truly “accepted” the practice. Complaints have been aired periodically, and the DOLE has not been remiss in reminding employers that the practice is illegal. But employers go on their merry way, and young workers seeking jobs in an uncertain (even if improving) economy and job market have little choice but to accede to the onerous conditions.

The reality is that the DOLE just doesn’t have enough personnel to fully monitor employers, while workers would settle for finding a job—any job that pays a wage even if only for a few months at a time—rather than risk continued joblessness.

* * *

AT the final presidential debate, almost all the candidates promised to bring an end to the days of “endo,” even if some of them are government officials who could certainly have done something about it in all their years in public service.

As expected, during the May 1 Labor Day rallies, workers’ groups echoed the calls for an end to “endo.” But it seems security of tenure takes a back seat to security of living, when workers are willing to put everything aside, even their rights and entitlements, in exchange for a steady wage that would assure them of a steady income, even if this comes only in five-month spurts.

Business people argue that in uncertain times, one of the factors that they seek to control is their labor costs, keeping wages down by limiting workers’ salaries and privileges and ensuring that most remain at entry level.

Which is how businesses have come up with creative means to keep workers and employees on a short lease without committing to any long-term career planning or development. Many resort to hiring on a “per project” basis, even if it’s pretty obvious that most of the projects come to an end in five months’ time. Others argue that those hired on a contractual basis do work that is not essential to the business, which is why they are hired through an outside agency. But, to take one example, how can, say, camera operators of a TV network be considered “nonessential” when without them no material can be aired?

* * *

TRUE, “endo” is an issue whose time has come—if it is not in fact long overdue. Whoever emerges the winner in the presidential race may have to take the issue seriously, even if putting an end to contractualization—or its worst manifestations—may tarnish rosy employment statistics or court the ire of big businesses and even lead to the closure of smaller enterprises.

But there IS a law against labor-only contracting, and the first step that should be taken is to simply enforce the law, which means committing the budget to hire more inspectors and beef up the necessary legal machinery to pursue offenders and fix the system.

Plus, of course, finding the proverbial “political will” to go after erring employers, who sap the young members of the work force of any hope for a brighter future with the steady, soul-draining cycle of finding-then-losing-employment, with hardly any training or human resource development undertaken.

* * *

“ENDO” the movie, if I remember right, ends on a hopeful note when our young male protagonist decides it is time to bring an end to his prevarication and denial and finally commits to a long-term relationship with his girlfriend.

In the real-life “endo,” the commitment-phobe is not the worker but the employer, and, in a way, also the government. I have argued in this corner many times that the gains to be made from ensuring security of tenure for workers far outweigh any short-term advantages from the revolving-door employment policy.

For one thing, a secure employee is a loyal employee, who ties his or her welfare and future to the welfare and future of the company where he or she works. Of course, there will always be the few who take advantage and begin slacking off the minute they make “permanent” status. But far more will realize that their long-term advantage rests on investing their time, talent and loyalty to a single employer for whom the workers’ good redounds to the good of the enterprise as well.