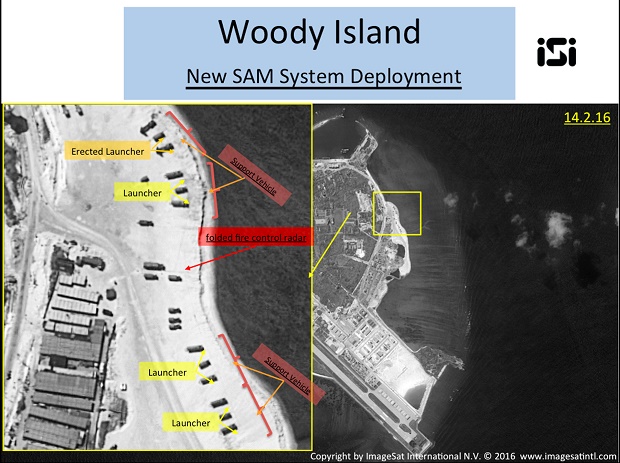

This image with notations provided by ImageSat International N.V., Wednesday, Feb. 17, 2016, shows satellite images of Woody Island, the largest of the Paracel Islands in the South China Sea. A U.S. official confirmed that China has placed a surface-to-air missile system on Woody Island in the Paracel chain, but it is unclear whether this is a short-term deployment or something intended to be more long-lasting. (ImageSat International N.V. via AP)

A ratchet is a mechanical device, usually with a wheel made of angled teeth, which allows movement in one direction. The familiar phrase “ratchet up” means an increase in tensions or a deterioration in a situation that is—because the movement is only in one direction—likely irreversible. Under this definition, China’s militarization of the South China Sea is a classic case of ratcheting up, and it carries ominous consequences for the region.

First, Beijing embarked on a program to transform at least four of the disputed reefs in the Spratlys into man-made islands, through an aggressive land reclamation project. In the view of both non-neutral experts and independent observers, the size of the reclamation meant the enlarged islands could support military facilities.

Second, Beijing has apparently constructed at least six high-frequency radar towers in the four man-made islands, including at least two on Cuarteron Reef. The Daily Mail quotes the Center for Strategic and International Studies on the significance of the radar installations: They “speak to a long-term anti-access strategy by China—one that would see it establish effective control over the sea and airspace throughout the South China Sea.”

Third, Beijing has deployed surface-to-air missiles on Woody Island in the Paracels, another cluster of disputed reefs, islets and islands in the South China Sea.

Both the defense ministry of Taiwan and the US defense department confirmed the existence of the “air defense missile system” (as a Taipei spokesperson described the facility).

Fourth, Beijing deployed fighter jets to Woody Island just in the last week—something that has happened before but whose significance now, at a time of greater regional tensions, cannot be underestimated.

These and other actions have taken place while China’s neighbors protested, or perhaps even as a calibrated response to the regional community’s continuing push for a peaceful resolution of competing maritime and territorial claims. Just last week, the leaders of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations met in California with US President Barack Obama, and together issued an appeal for greater restraint; in Obama’s words, for “a halt to further reclamation, new construction and militarization of disputed areas.”

It seems clear that Beijing is determined to look past these protestations. Foreign Minister Wang Yi belittled the controversy over the apparent militarization of the disputed islands, calling it “an attempt by certain Western media to create news stories.”

There is a difference in the way Beijing treats the Paracels from the Spratlys; it has exercised effective control over most of the Paracel Islands from the 1970s. It has asserted its increasingly expansive rights to the Spratlys, and thus to the Philippine claims, only in the 1990s. The difference explains why the air defense missiles were deployed on Woody, while (for the moment) only radar installations, lighthouses and landing pads are being constructed on Cuarteron and other artificial islands in the Spratlys.

But the CSIS analysis is right: The long-term goal of denying access to the area, including to large parts of the West Philippine Sea, is clear.

We read these concerted actions as Beijing’s strategic response to the Philippine lawsuit pending in an international arbitral body under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea. It is readying itself for an adverse ruling, and, under the simple legal axiom that holds that possession is nine-tenths of the law (or whatever the count is in Chinese tradition), has moved rapidly to consolidate its hold on the disputed islands.

We must protest this ratcheting up of tensions, and we must once again ask our allies and partners in the international community to join their voice to ours. China is a signatory to Unclos, as it is to many international agreements; it cannot simply do away with crucial provisions of international law if these are not to its liking, and by sending in the fighter jets. A wheel’s angled teeth can bite both ways.