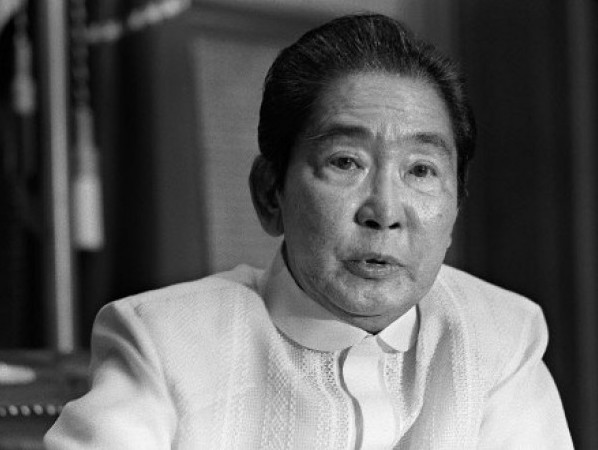

30 years without the dictator

NEXT WEEK the Philippines celebrates the 30th anniversary of the Edsa People Power Revolution, which toppled the authoritarian regime of Ferdinand Marcos that prevailed for 13 years and five months, and which restored democracy with Corazon Cojuangco Aquino as president.

The evidence that the country has benefited exceedingly from that historic event three decades ago is superabundant.

In 1984 and 1985, national surveys by the Bishops-Businessmen’s Conference for Human Development (BBC) showed great public disapproval of the Marcos dictatorship. The two surveys were done on April 3-24, 1984, and June 15-July 22, 1985, respectively. Both surveys had samples of 2,000 adults, quite large by world standards; the golden rule for a national sample is only 1,000.

READ: I saw martial law up close and personal

The 1984 BBC survey asked, “From September 1972 up to now, the president has been issuing laws by decrees, whereas before only the legislature could make laws. Do you favor this system or do you think only the Batasan should have the power to legislate?” It found 60 percent disapproving of Marcos’ power to issue decrees, and 36 percent wanting laws to be made only by the Batasang Pambansa. When the question was repeated in 1985, the result was 61 percent disapproval of presidential decrees, and 34 percent preference for legislation by the Batasan.

READ: Bongbong Marcos is right: Why should he say ‘Sorry?’

The 1985 BBC survey had another question: “Another sole prerogative of the president is to detain in prison a person who he thinks is dangerous to society, and who cannot be freed without his approval, no matter what the court says. Do you agree with this system?” It found 65 percent against, and only 30 percent in favor of Marcos’ power to order preventive detention.

The 1985 BBC survey also found Self-Rated Poverty at 74 percent, which is the all-time high to this day. (It was the second-ever national survey on Self-Rated Poverty. An earlier one, done in 1983 by the Development Academy of the Philippines but unpublished, had found Self-Rated Poverty at 55 percent.)

READ: Marcos diaries: ‘Delusions of a dictator’/Marcos diaries: ‘Hysteria in Manila… I must declare martial law soon’

The first post-Edsa survey showed a low public regard for Ferdinand Marcos as a person. In May 1986, Social Weather Stations and Ateneo de Manila University jointly did a scientific public opinion survey of 2,000 adults nationwide.

In this survey, six out of seven questions on Marcos’ character elicited unfavorable responses, as follows (in bold type):

Statements about Marcos: Yes (%) No (%)

“Caring for friends who enriched themselves by pocketing 54 33

government funds?”

“Favoring foreign interests in our country?” 54 32

“A deceiver or a liar?” 51 35

“A thief of the nation’s wealth?” 51 34

“True to the duties of a patriotic president?” 41 47

“Defender of the poor and oppressed?” 30 52

The single character-related question with a favorable response was on whether Marcos was “A brave president.” This got 69 percent Yes, and 25 percent No.

Although public satisfaction with the working of our democracy has had ups and downs, most Filipinos say they always prefer democracy, and only a few say they sometimes prefer authoritarianism.

Since 1991, SWS has surveyed public satisfaction with the way democracy works (an item borrowed from Eurobarometer) 57 times. The percentage satisfied usually peaks after successful election exercises. It reached 70 in 1992, 70 again in 1998, 69 in 2010, the record-high 80 in 2013, and 77 most recently in June 2015. It dropped a lot in the time of Gloria Arroyo, who got the record-low 28 percent (November 2003). In contrast, the lowest percentages of Presidents Cory Aquino, Ramos, Estrada, and Noynoy Aquino were 45, 46, 47 and 64 respectively.

Since 2002, SWS has surveyed, 23 times, if respondents feel that: (a) democracy is always the best form of government, or (b) authoritarianism is better in some situations, or (c) having democracy or not doesn’t matter to people like them. Those feeling that democracy is always best has been the majority in all times but one (September 2006, 49 percent). The remainder are split between those favoring authoritarianism and the indifferent.

Even in November 2003, when only 28 percent were satisfied with the working of democracy, 58 percent said democracy is always best, and only 20 percent said authoritarianism is sometimes better. (This survey item is borrowed from Latinobarometro, which covers countries with a history of intermittent military coups and coup attempts.)

In conclusion, it is not true that the Marcos regime gave Filipinos a liking for authoritarianism.

After the Marcos regime, Filipinos became free to criticize the government. When the 1985 BBC survey tested the statement “I can say anything I want, openly and without fear, even if it is against the administration,” it found that 33 percent agreed, 29 percent disagreed and a plurality of 38 percent were undecided. The difference between the two sides, of +4 points, is an indicator of freedom of speech. It was virtually nil in 1985.

By May 1986, in the SWS-Ateneo survey, 58 percent agreed, and only 19 percent disagreed, that they could speak freely even against the government. This boosted the “net freedom” score to +39. In 38 SWS surveys over 1986-2015, the agreement has been below half only 4 times. Net freedom exploded to +63 in March 1987—i.e., after the new Constitution was ratified. Its lowest point in the restored democracy was +16 (September 1988); the latest is +34, in December 2015.

For us in opinion polling, freedom of speech is the most important attribute of democracy.

* * *

Contact mahar.mangahas@sws.org.ph.