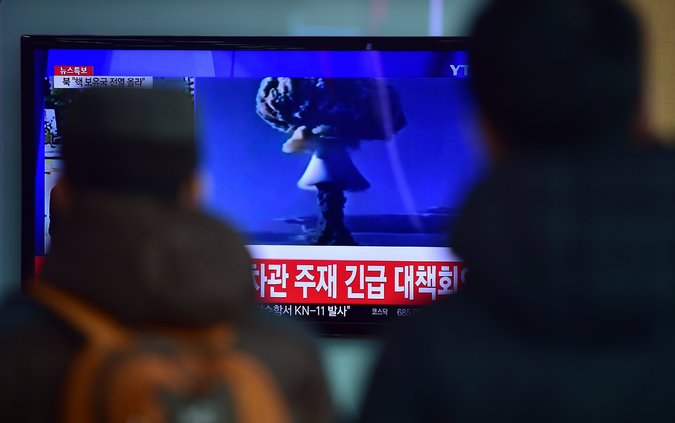

H-bomb horror

People in Seoul, South Korea, watched a news report on North Korea’s announcement of its first hydrogen bomb test. Jung Yeon-Je/Agence France-Presse

A 5.1 earthquake occurred at 1:30 a.m. last Thursday that, while striking a remote region of the earth and registering no casualties or destruction of property, nevertheless got the world sitting up and taking notice. The temblor, originating in the northeastern part of North Korea, appeared to international observers and monitoring stations to be, not tectonic in origin, but the result of a nuclear test.

North Korea eventually announced that the underground explosion was a successful test of its new bomb—a hydrogen bomb. That immediately sent off alarm bells across much of the international community, spawning news reports of world leaders huddling in top-level meetings with their security cabinets to discuss the implications of what appeared to be a disturbing advance in the pursuit of thermonuclear weapons by one of the world’s rogue states.

Article continues after this advertisementBut was it really a hydrogen bomb? The United States is apparently trying to contain any propaganda mileage that North Korea is hoping to reap from its startling announcement by publicly expressing skepticism at this time. For one, the magnitude of the blast appeared to be much smaller and more limited than one associated with a thermonuclear explosion. At 5.1, the tremor generated by the purported test was just about the same level as the atomic bomb believed to have been test-detonated by North Korea in 2013. Its two other earlier atomic tests registered lower at 4.1 (2006) and 4.5 (2009).

Because North Korea is one of the world’s most barricaded states and freely admitting international observers to monitor data from its blast site is well nigh impossible, it would take a while before experts can conclusively say that it has indeed reached a new threshold in the arms race, or it is merely rattling its saber once again to extract leverage in the international community.

“In the past,” noted the New York Times in a primer on the issue, “United States administrations and South Korean governments managed to tamp down periodic heightened tensions with North Korea by offering concessions, including much-needed aid, in return for the North’s promising to end its nuclear weapons programs. Many analysts believe that North Korea is again seeking aid and other concessions, while some suggest that it merely wants to be recognized as a nuclear state, like Pakistan.”

Article continues after this advertisementOnly five countries are known to possess hydrogen bombs at this point—America, Russia, Britain, France and China. The other nuclear-armed nations are believed to have atomic bombs, which are a different breed of weapons. Atom bombs rely on fission, or the splitting of the atom, to trigger their detonation. H-bombs, on the other hand, use a process called nuclear fusion—the melding of atoms—which generates energy that’s 500 times more explosive and destructive than a conventional atom bomb. “Fat Man” and “Little Boy,” the bombs that wiped out Nagasaki and Hiroshima and killed some 200,000 people, were measured only in kilotons. The first H-bomb tested by the United States in 1954 was already 15 megatons, or a thousand times more powerful than the blasts that brought Japan to its knees and ushered the world into a horrifying new age.

A day after North Korea’s announcement, the United Nations Security Council condemned its nuclear test. But beyond the words, there is not much the world can do at this point to rein in North Korea, or any other nation sufficiently stubborn to develop its own nuclear weaponry. That logjam arises from the sheer warped setup engendered by the arms race, in which countries with known nuclear capabilities censure upstart countries about slowing down or altogether scrapping their push for weapons of equal deterrence and power, unmindful of the ascendancy they lack to impose such a moral stance by their ironic example.

The sensible response, it would appear, is to push for general disarmament, and for the world community—as is being shown with climate change—to reach a consensus that fewer, not more, terrifying weapons is the ideal goal for the future. But in the screwed-up world of international realpolitik where deterrence rests on the idea that nations being armed to the teeth is in fact the guarantee to peace, calls for deescalating the continuing scramble for instruments of mass death and destruction are deemed a woolly, hippie pipe dream.

And now it’s North Korea’s turn to enter the exclusive H-bomb club—if indeed it has managed to make one. Who’s betting it would be the last country to attempt to do so?