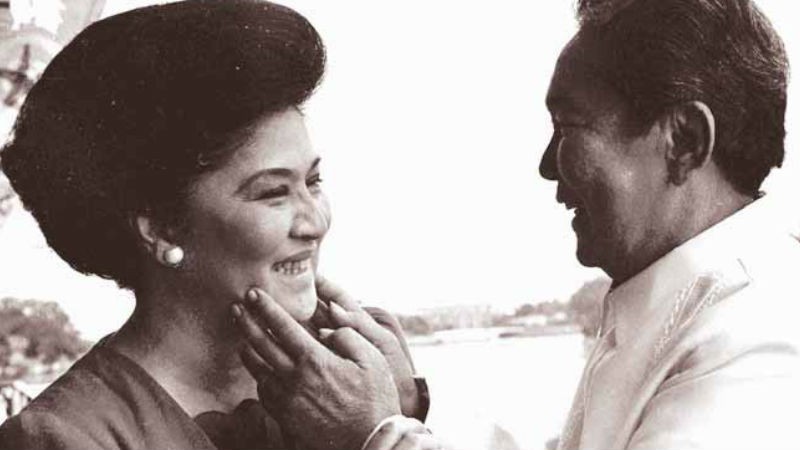

NO WONDER the Marcoses can think of ruining—este, running—the country again. Faced with some 300 civil cases involving ill-gotten wealth, with Imelda Marcos herself dealing with 10 graft charges, the Marcos family has nevertheless managed to evade the increasingly feeble arm of Philippine justice.

Their cronies—that is the term we have learned to use to describe the close friends of Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos; they took mutual advantage of the closeness to amass great wealth and forge economic empires, creating what is now called crony capitalism—have had their day of reckoning before the courts; the Marcoses themselves, unapologetic and unrepentant, have dodged one legal bullet after another.

The latest case resolved against a crony is also the latest proof of the Marcos family’s unusual dexterity. Some may be truly smarter than others, as Imelda famously said in her heyday.

On Dec. 14, the Sandiganbayan ruled on a 24-year-old case. It ordered the late Marcos crony Alfonso Lim Sr. and his family to return to the government some 600,000 hectares of special logging concessions.

Reporter Marc Jayson Cayabyab’s summary of the case is succinct:

“Lim is accused of collusion with Marcos and former First Lady (now Ilocos Norte Rep.) Imelda Marcos to obtain several timber concessions beyond the allowable 100,000 hectares of land under the 1973 Constitution.

“Lim was accused of holding 533,880 hectares of land under seven corporations, far exceeding the allowable 100,000 hectares of land.

“But the court noted that Lim actually had access to 633,880 hectares of forests, because of the wide expanse of forest lands in between Lim’s different timber concessions.”

The post-Marcos government brought suit in 1991, accusing Lim and his group of “taking undue advantage of their relationship, influence, and connection with [the Marcoses] … to unjustly enrich themselves at the expense of the Republic and the Filipino people.”

The Sandiganbayan agreed with the government. But here’s the rub: Though Marcos, his wife Imelda, and their family were impleaded in the case, the antigraft court did not say anything about their liability.

We find this worrying. There is good evidence to show that Marcos himself took a close and personal interest in Lim’s transactions; a tumultuous boardroom contest in 1979 was resolved when Lim announced that “the contract was approved by the President.” It is also clear that Lim enjoyed unusual privileges. The Sandiganbayan quotes a previous Supreme Court decision: “so influential was Lim Sr. that he and Taggat [Industries] and other sister companies received certain timber-related benefits without the knowledge, let alone approval, of the Minister of Natural Resources.”

How is that possible, in a tightly controlled dictatorship? Only if the “certain timber-related benefits” were granted with the knowledge and approval of either the dictator or his wife.

The Supreme Court wrote: “Lim Sr. doubtless utilized to the hilt his closeness to the Marcoses to amass what may prima facie be considered as illegal wealth.” It’s a great pity that the Sandiganbayan did not follow the lead of the high court’s reasoning, and find that there could have been no amassing of illegal wealth without the knowledge, let alone approval, of Marcos or Imelda.

Key to the Sandiganbayan ruling was a 1986 report prepared by the Ministry of Natural Resources after Corazon Aquino had assumed the presidency. It placed the concessions Lim enjoyed in perspective: The presidential favors he received, the report said, “effectively increased the total hectarage under his management and control to 533,880 hectares, unequalled and unprecedented in Philippine Natural Resources history.”

It is good that, after a quarter of a century, the record has been straightened, the judgment has been rendered, and the recovery of the properties can begin. But precisely because it has taken such a long time (Lim died in 1995), we cannot but suspect that the lack of dispatch and urgency has contributed to the failure to exact accountability. We ask: Can there be Marcos cronies, without a Marcos?