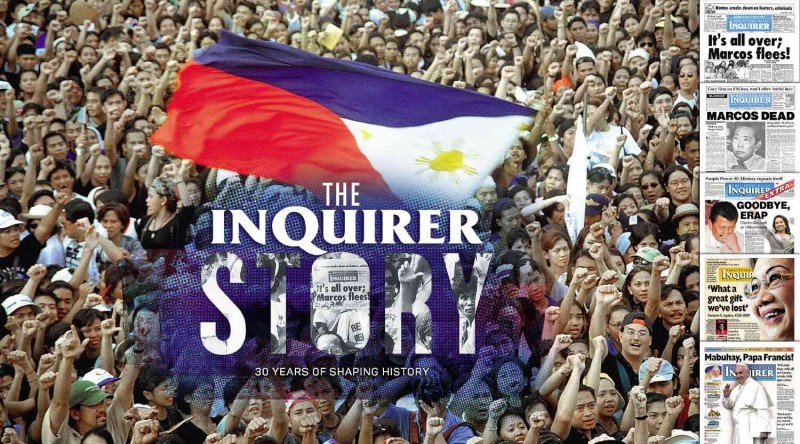

PAPER POWER The cover of the 30th anniversary book “The Inquirer Story: 30 Years of Shaping History” celebrated people power from both Edsa I and II. On the right are five of the most memorable Inquirer front pages over the last 30 years. BOOK COVER DESIGN: RICARDO VELARDE / LYNETT VILLARIBA

It was December 1985 and the rented office in the Port Area building was crowded with Eggie Apostol’s editors, reporters, photographers, other personnel—and an overwhelming sense of purpose. As though to foreshadow the shape of things to come, a brief power outage marked the eve of the newspaper’s inaugural, and reports had to be written and edited by shaky candlelight, by hand and on (a few) typewriters. Even so, the Philippine Daily Inquirer, its front page famously looking like “an unmade bed,” came into being. Even then, it managed to beat the odds.

The Marcos regime was on its last legs, the effects of the 1983 assassination of Ninoy Aquino coming to a head and the steady, stirring inroads of his widow Cory chipping away at the dictatorship’s base. The strongman tried to revive his crumbling apparat by announcing a snap election in February 1986. The fledgling newspaper covered history and put out the momentous headline: “Marcos flees!”

Fast forward to 30 years later, and the Inquirer continues to deliver the news and commentary that make history. But today, operating from its own buildings in Makati, it does so in various platforms to reach a fast-changing, ever-widening readership. From print to online to mobile to digital, Twitter, Instagram, video, and radio broadcasts, Inquirer Multimedia can be accessed anywhere, anytime.

As the newspaper grew its readership, it built strength and stature, gathering awards and recognition for its groundbreaking reports, eventually becoming No. 1 in the industry. Agenda-setting is, after all, part of the Inquirer DNA. It kicked in during those tumultuous days before, during and after Edsa 1, when Filipinos hungry to learn about the unfolding events turned to the newspaper for unvarnished news that others had been too timid, too browbeaten, to report. No wonder the Edsa People Power Revolt has often been described as the media revolution, with the Inquirer firmly at front-row center.

In last weekend’s launch of “The Inquirer Story: 30 Years of Shaping History,” Inquirer president Sandy Prieto-Romualdez defined our reportage philosophy: “We do not believe that there is such a thing as ‘alternative press’—as counterweight against a so-called ‘crony press.’ There is only one kind of journalism and it is neither ‘alternative’ nor ‘crony.’ It is journalism that reports the facts, neither tailoring them to suit our friends, nor twisting them to dismay or destroy our enemies.”

Such a philosophy was severely put to the test when then President Joseph Estrada sought to temper the Inquirer’s coverage of the anomalous goings-on under his watch by instigating an advertising boycott. Cutting off ad revenues—a major source of income of any newspaper—was a severe, trying blow, as was the pressure exerted by interested parties who offered the metaphorical blank checks. But support from loyal advertisers and other friends, as well as the touching efforts of readers nationwide to shore up the Inquirer, helped it stand its ground. It has similarly defied pressure from other politicians to dampen its zeal in exposing anomalies. Its historic series of reports on the pork barrel scandal proves its continuing commitment.

Today, even with paper costs and cutting-edge technology presenting the latest threats to the print medium, the Inquirer looks to the future with undiminished courage and passion. It remains and will remain a critical presence in the public arena, prepared to report and to criticize and appreciate when warranted. Because while the medium and technology may change, while media platforms may tilt toward a shorter attention span, the Inquirer’s voice will endure and will continue to provide the public with informative reportage and incisive discussion of the burning issues of the day.

As Prieto-Romualdez maintained, “The public has been very much a part of our history, the one thing that has made the Inquirer successful… Just when you feel like giving up, someone’s going to pull you aside and say, ‘Thank you for the Inquirer.’ This is for them.”