ON NOV. 1, the Philippine Daily Inquirer published in Talk of the Town a disturbing article written by Carlo Arcilla, PhD, on the flawed P350-billion master flood-control project of the Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH). The article provided scary insights into a practice that we have employed for decades, a system that erodes the very core of our existence as Filipinos and the future of our nation.

Concerns

Arcilla’s take on the big-ticket master flood-control project, an offshoot of a World Bank-funded study to prepare a comprehensive flood-risk management plan and programmed from 2013 to 2035, raises the following:

- Inadequate model used to propose solutions to flooding in Metro Manila

- Myopic view of the problem, raising questions on the effectiveness of the flood-control project

- Questions on the amount of the National Economic and Development Authority (Neda)-approved P350-billion master flood-control project pro- posed by the World Bank

- Big-ticket flood-control project as a vehicle for corruption and exploitation

Since the article mentioned Project Noah (Nationwide Operational Assessment of Hazards) of the Department of Science and Technology (DOST), I thought it best to write this article to provide further insights into and advance the discussion on the topic. But before I begin, it is worth noting that flooding in Metro Manila is extremely complex and difficult to solve with both technical and political concerns in mind.

The opinions hereby presented are merely to put the discourse in proper perspective for consideration by the government and the general public.

Inadequacy of flood model

The flooding problem in Metro Manila is multifaceted. These involve river floods, urban or street floods, dam failure, tidal floods, tsunamis and storm surges.

To make things simple, I categorize the different kinds of flooding concerns in Metro Manila into nuisance and those that kill.

Nuisance floods are related to brief thunderstorms that deliver heavy rainfall over a span of about an hour. These short-lived rain events make creeks swell and spawn street floods that cause mammoth traffic jams in the metropolis, costing the Philippine economy P2.4 billion a day from wasted gasoline and lost opportunities.

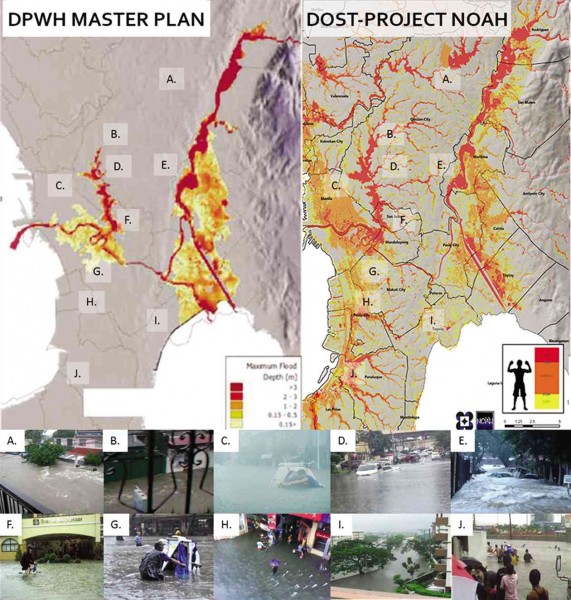

Street floods will not be solved by the master plan primarily because the World Bank assessment does not include an analysis of the street-flood problem as identified by the Metropolitan Manila Development Authority. (See Figure 1.)

Using the Project Noah method to identify flood-prone areas in Metro Manila, it is possible to find solutions to flooding in many streets. A more detailed discussion on this problem can be found at www.blog.noah.dost.gov.ph/2015

/11/09/street-floods-in-metro-manila-and-possible-solutions.

Floods that kill, which we are familiar with and have recently experienced, are the Tropical Storm “Ondoy” and habagat (southwest monsoon) floods in Metro Manila. These extreme and prolonged rain events made the Marikina River rise dramatically by as much as 11 meters during Ondoy in 2009, 9.5 m during Habagat 2012, 8.9 m during Habagat 2013 and 8.8 m during Habagat 2014.

The range of the rise in the water level of the Marikina River was equivalent to a three-story building. When rivers swell by this much, destructive floods in flat areas near waterways are inevitable, even with protective dikes.

Timely warning and appropriate response of the residents of Marikina averted three potential disasters during the onslaught of three consecutive years of extreme habagat rains. Flood hazards in areas near rivers like Marikina will always be there but knowledge of the risk and preparedness can be used to avoid loss of lives.

There are two nonexclusive ways to address the problem of flood hazards that kill: One is by building expensive flood-control structures and the other is through nonstructural means—knowing the risk and getting out of harm’s way when there is imminent danger, or planning ahead by developing communities that are out of harm’s way.

The master plan mainly deals with structural control. This begs the question on the wisdom of investing hundreds of billions in infrastructure to solve the flood problem of the nation’s capital, when there are flood problems in nearly every corner of the country.

Myopic view

It is important that the problem be understood well before a solution is provided. With the availability of powerful computers and state-of-the-art instruments that map the landscape in high-resolution, scenarios of floods can be simulated, enabling us to identify areas where there is danger from floods.

Furthermore, structural intervention can be checked for its usefulness even before the infrastructure is built.

The DPWH did present a “before-and-after flood scenario,” but only modeled the Marikina and San Juan Rivers, and not the network of river arteries that lead to the two main waterways. The Ondoy event taught us that areas in Metro Manila near creeks and streams could also flood and pose danger. There were destructive floods in numerous places aside from the areas beside the Marikina and San Juan rivers. (See Figure 1.)

Groundwater extraction

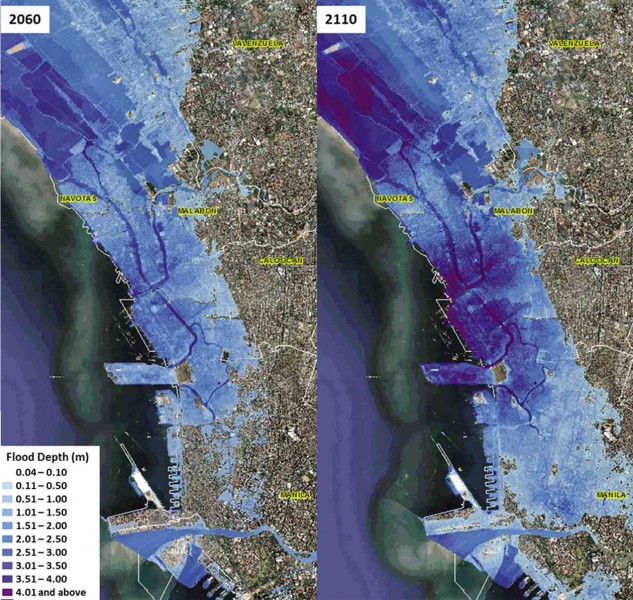

Compounding our flood problems in the metropolis is excessive groundwater extraction, which leads to sinking of the ground at alarming rates of about 5-6 centimeters per year (www.opinion.inquirer.net/12757/large-areas-of-metro-manila-sinking).

This rate of sinking is an order of magnitude higher compared with sea-level rise, which is only about 2-4 millimeters per year.

Like sea-level rise, the effect of ground sinking is to inundate coastal areas. However, the rate of ground sinking in parts of Metro Manila is more alarming. At the current rate of ground subsidence, many coastal areas will be inundated by up to 2-4 m during high tide a hundred years from now. (See Figure 2.)

To prevent the grim scenario of flooding in coastal areas, it is prudent to spend resources to stem the root of the ground-sinking problem. Sufficient supply of surface water must be provided to dispel overextraction of aquifers.

Review budget

The master plan has not yet considered more advanced technologies to completely understand the flood problem. Hence, a reassessment of the budget for the project is in order.

Neda, in its response to Arcilla’s commentary, has come up with a statement that individual projects in the master plan are subject to the Investment Coordination Committee’s multidisciplinary evaluation and appraisal. Any proposed project with a budget of P1 billion and above will have to undergo a rigorous evaluation process to determine feasibility, cost-effectiveness and overall economic and social benefits.

Socioecomic Planning Secretary Arsenio Balisacan, also Neda director general, further said that components of the master plan were subject to further refinements. Noting, for instance, that at the time the flood management master plan was being developed in 2011, data from Project Noah, which was launched on July 6, 2012, were not yet available.

Nonetheless, during the Infracom deliberations, Public Works Secretary Rogelio Singson said that some of the principles of Project Noah would be adopted. It was understood that in the conduct of feasibility studies for the components of the master plan, other available studies and information would also be considered.

Engaging Filipino scientists

To avoid the same predicament as the Philippine Republic vs Baggerwerken trial in Washington (international arbitration case in the World Bank, 2014), regarding the P29-billion Pasig and Laguna de Bay dredging projects, competent Filipino engineers and scientists should at least comment on the technical feasibility and do the requisite modeling before money is borrowed and spent.

Apart from our capability to test the effectiveness of flood-control infrastructure by engaging our local scientists and engineers instead of foreign consultants, we also help Filipinos in the practice of their profession.

Doubts, transparency

Project Noah was invited in October by Neda to participate in the discussions in the last World Bank mission on the socioeconomic scorecard. After hearing the presentation of the World Bank technical team, it became clear that its flood-hazard models to calculate risks used a regional and low-resolution model for floods.

The DOST pointed out that the Philippines had more detailed flood models, which when used would yield better estimation of socioeconomic resilience as a tool to identify policy priorities. Moreover, the DOST mentioned that the Project Noah team had been working since 2013 on WebSAFE, a joint effort with the World Bank to calculate risk at the municipal level using detailed flood-hazard maps.

In the meeting, Balisacan made sure that there was no duplication by World Bank and that efforts be synchronized in order to avoid waste of funds that will ultimately be paid for by the Filipino taxpayer.

During the onslaught of Typhoon “Lando” in late October when heavy rains brought extreme floods to the municipalities of Nueva Ecija, Singson, a strong supporter of Project Noah, called Interior Secretary Mel Senen Sarmiento, who at the time was at the operation’s center of the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council.

Fearing floods would inundate the downstream municipalities of Pampanga River, Singson asked if Project Noah could make projections on the flooding that would ensue to which we answered that the municipalities of Calumpit and Hagonoy would start to flood on Oct. 19, and remain flooded for several days and up to weeks.

If the actions taken by Balisacan and Singson in these anecdotes are to be made a measure of the verity of the Neda statement, we can be assured that local scientists and engineers will be able to vet and refine the individual projects of the master plan and its budget.

Guiding principles

The Neda statement mentioned that some of the principles of Project Noah would be adopted. These are some of the guiding principles we follow to help the country avert disasters from natural hazards:

Noah, being mainly composed of academic researchers, believes in the power of science and the use of the most advanced technologies at the forefront of the battle against disasters.

Consistent with the basic tenet of disaster prevention and mitigation on the use of local resources and capacity, employing local technology and scientists help us bring down costs and reach more people at risk from hazards.

For a developing country, this is crucial. While we don’t eschew the contributions of foreign experts, we have already developed our capabilities to assess what will be beneficial to us Filipinos and should not just import blindly technologies wholesale.

Ockham’s razor

As scientists, we use Ockham’s razor, the principle of choosing the simpler answer between two equally likely solutions to a problem. Between investing in getting people out of hazardous areas and building expensive defenses against floods, we choose the less costly, less risky and more natural means for disaster prevention and mitigation.

It is best to allow water to take its natural course and let the river flood plains accommodate floodwaters. In the Netherlands, the Waal River has been diked since the 13th century. Aside from dikes being expensive to maintain, devastating floods in the early 1990s made the Dutch rethink their old approach, which was to raise the dikes even higher.

Making room for river

Instead, they opted to make room for the river. This paradigm is now a worldwide trend in policy for disaster prevention and climate change adaptation, and is included in the sunset review of Republic Act No. 10121, the Philippine Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Act.

A structure built to protect a community from floods transfers the problem to another and should be in principle avoided. When the Manggahan floodway was built in 1986 to protect the City of Manila from flooding, the problem moved to the coastal areas of Laguna de Bay. During Ondoy and habagat floods, many communities around the freshwater lake were submerged for up to four months.

Vetting

The National Academy of Sciences and Technology, National Research Council of the Philippines, universities and the DOST have a lot of brilliant scientists and engineers. Like in other countries, not only must we support them in their academic work, they should also be tapped for vetting and decision-making for the government.

There is a simple reason why science is widely used by society—it works. Science has allowed us to better comprehend our world and make vast improvements in the way we live. Let us use this knowledge so our children will not have to endure costly nightmares their entire lives.

(Alfredo Mahar Francisco A. Lagmay is the executive director of Project Noah, the flagship disaster-preparedness and mitigation program of the Department of Science and Technology. He was awarded the Plinius medal this year by the European Geosciences Union for his outstanding interdisciplinary natural-hazard research and disaster mitigation engagement in the Philippines.)