Elpidio Quirino at 125: Our generation will be kinder

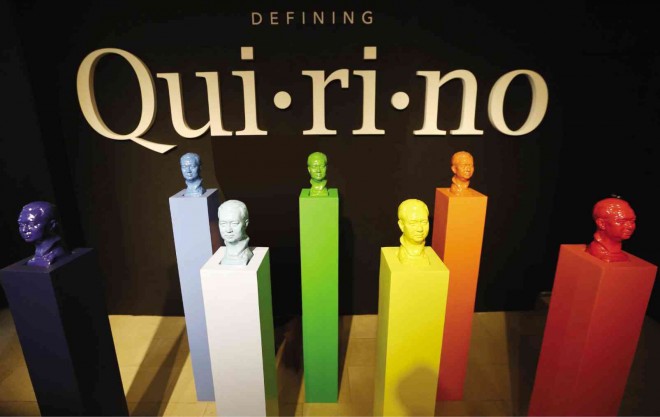

HEADS UP Sculpted using various media, a bust of the late President Elpidio Quirino forms part of the exhibit “Defining Quirino” at Ayala Museum in Makati. The exhibit, marking the 125th anniversary of Quirino’s birth on Nov. 16, features highlights in the life of the postwar reconstruction leader and shows the young new ways to contribute to nation-building. LYN RILLON

Elpidio Quirino (1890-1956) is often associated with the Luneta Grandstand that bears his name, or Quirino Avenue in Manila, where traffic moves at a snail’s pace during rush hour.

For Filipinos over 60, Quirino is the President with a “golden orinola” (bedpan) and a P5,000 bed that came to symbolize the alleged extravagance and graft and corruption of his administration.

There was no golden orinola, it turned out, and his Malacañang bed cost around P300, not P5,000. Yet these pieces of furniture have become the stuff of legend, burned into our consciousness because history has been unkind to Quirino.

An overpriced bed and orinola were created by his political enemies in a failed impeachment that damaged his reputation beyond repair.

But there is more to the second President of the Third Republic than a grandstand and a fictitious golden orinola.

“Some are born great, some achieve greatness and some have greatness thrust upon them,” said William Shakespeare in one of his celebrated lines. Quirino was of the third type.

Accidental President

Born 125 years ago on Nov. 16, 1890, in an Ilocos jail, where his father served as prison warden, Quirino first became President of the Philippines on April 17, 1948, two days after Manuel Roxas’ heart stopped beating.

Quirino inherited with the office the challenge of rebuilding a Philippines physically and spiritually destroyed by World War II.

In 1949, he won a full term on his own, defeating Jose P. Laurel in elections since described as the dirtiest in Philippine history. The Liberal Party was swept into power in elections where plants, animals, and even the dead cast their ballots.

With a tarnished reputation, Quirino lost a bid for reelection against Ramon Magsaysay in 1953.

It is not generally known that certain laws and institutions we appreciate today were established during Quirino’s term. He signed into law the Minimum Wage Law of 1951 (Republic Act No. 602) and the Public School Salary Act of 1948 (Republic Act No. 312). The hydroelectric plant in Maria Cristina Falls (Mindanao) and the Ambuklao dam (Luzon) were established under Quirino.

The designation of Quezon City as capital of the Philippines, its master plan and the donation of the Diliman property to the University of the Philippines for a token P1 was also achieved during his term.

Controversial issues

Hairsplitting being a historian’s pastime, hours and hours of fun will be had on these two controversial issues: Is Quirino the “father of foreign service”? Of the Central Bank? As Vice President, Quirino served as secretary of foreign affairs from 1946-1948. As President in 1951, he signed into law Republic Act No. 708 that reorganized and strengthened the foreign service into what it is today.

Consequently, some historians consider him the father of foreign service. However, our foreign service traces its beginnings to the Philippine Revolution and Apolinario Mabini.

Perhaps looking at foreign service in terms of generations will settle the issue: Apolinario Mabini, the first foreign minister of the First Republic, can be the “great grandfather of foreign service”; while Claro M. Recto, foreign minister of the Second Republic, can be considered the “grandfather of foreign service”; resulting in Quirino, the first foreign secretary of the Third Republic, being the father of foreign service.

Another issue concerns the Central Bank that traces its beginnings to Manuel Roxas, now depicted on the P100 bill with the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas building. If Roxas is considered the “grandfather of the Central Bank,” Quirino can be the “father of the Central Bank,” that was legally and formally established on June 15, 1948, with Miguel Cuaderno as its first governor, under Quirino’s watch.

Humanitarian acts

Quirino’s most important acts, however, were not political but humanitarian. In 1948, he declared an amnesty that led to the surrender of Huks, including Luis Taruc.

Following the example of Manuel Luis Quezon who offered asylum to Jews fleeing from the Nazis, Quirino accepted 5,880 “White Russians” who fled from Maoist China in 1949. These White Russians were settled in Tubabao, Guiuan, Samar, for three years.

Quirino visited the settlement and was quoted to have said: “We believe that freedom engenders responsibility, and this responsibility involves a solemn obligation to humanity.”

In 1950, Quirino sent the 7,500-strong Philippine Expeditionary Forces to Korea or Peftok, the fourth largest delegation under the United Nations command. The group was sent off with these words: “I sent ahead of you my only son (Tomas Quirino) and son-in-law (Luis Gonzales) to offer their blood in defense of democracy. Thus, my pride will be that with my own flesh and blood, I shall have participated in your coming struggle and victory, for the honor and prestige of our country.”

Unpopular clemency for Japanese

Then in 1953, Quirino granted clemency for Japanese prisoners of war in Muntinlupa.

It was an unpopular decision that he explained in these words: “I should be the last one to pardon them as the Japanese killed my wife and three children, and five other members of my family. I am doing this because I do not want my children and my people to inherit from me the hate for people who might yet be our friends for the permanent interest of our country.”

Quirino was a teacher who became President. He died of a heart attack on Feb. 29, 1956, without fulfilling his ambition to retire from Malacanañg and return to teach in a barrio school.

Nevertheless, Quirino’s life has many lessons to teach us. And when our generation writes our own history, it will be fair to Quirino and it will not just highlight the evil that lives after him, but to exhume the good that Shakespeare says is “interred with their bones.”

RELATED STORIES

Youth could learn a thing or two from Quirino legacy

Elpidio “EQ” Quirino: The President who forgave his loved ones’ killers