International law the ‘great equalizer’

PHILIPPINE officials and lawyers at the Peace Palace in The Hague before the start of oral arguments against China’s claims over the West Philippine Sea.

Filipinos who have held their breath over the wisdom of the country’s legal and diplomatic gambit should rest a little easier after two developments in the South China Sea dispute last week.

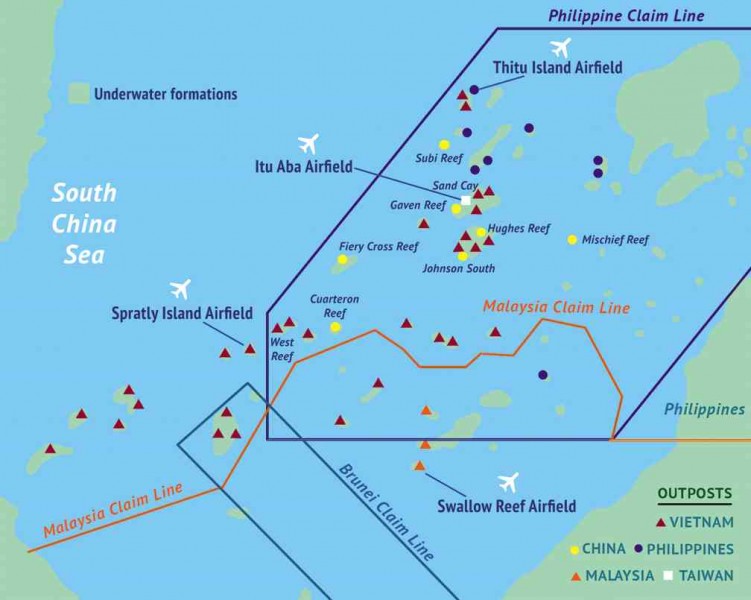

The news that the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) in The Hague had ruled on jurisdiction and that the United States had sent the USS Lassen within 22 kilometers off Zamora (Subi) Reef are both positive signs for our prospects for a fair and lawful resolution of the dispute.

Article continues after this advertisementIn the first breakthrough, the PCA announced the tribunal’s ruling that it had jurisdiction over the case that the Philippines presented in oral hearings in July.

Of the Philippines’ 15 “submissions,” the tribunal found that it had jurisdiction over seven and that it would reserve its consideration of jurisdiction over a further seven for the merits phase of the proceedings.

The tribunal directed the Philippines to clarify and narrow the scope of one submission. (Interested readers can find the entirety of the PCA’s release on its website.)

Article continues after this advertisementClear win

This is a clear win for the Philippines, which turned to the international tribunal in 2013 not long after Philippine and Chinese vessels had a standoff at Panatag (Scarborough) Shoal in 2012.

After both sides withdrew from the shoal, Chinese maritime assets returned and prevented Filipino fishermen from continuing to pursue their livelihoods there.

The standoff fomented Filipinos’ strong mistrust of China’s intentions over this issue, which was aggravated by China’s insistence on bilateral negotiations.

Having just “lost” Panatag Shoal, there was little reason to believe that beginning a head-on negotiation with the same power would result in a fair outcome.

Provocation

Unfortunately, China has not changed its position on bilateral negotiation and continues to reject the authority of the tribunal. After the PCA released its ruling, the Chinese Embassy in Washington said in a statement: “The Philippines’ unilateral initiation and obstinate pushing forward of the South China Sea arbitration by abusing the compulsory procedures for dispute settlement under the Unclos (United Nations Convention on Law of the Sea) is a political provocation under the cloak of law.”

In two respects, China is correct. The Philippines acted unilaterally in lodging a case in The Hague. China does not recognize the authority of the tribunal, despite having ratified the law of the sea convention. The Department of Foreign Affairs (DFA) obstinately pursued the case to gain clarity over maritime rights in the disputed area. From where we sit, however, this move is praiseworthy, not dishonorable.

Not abusive

In more important ways, China is incorrect. Pushing forward with arbitration is not abusive. Thanks to the DFA’s decision, you no longer have to take our government’s word for it.

We can quote the tribunal, which examined this specific matter: “The Tribunal has also held that China’s decision not to participate in these proceedings does not deprive the Tribunal of jurisdiction and that the Philippines’ decision to commence arbitration unilaterally was not an abuse of the Convention’s dispute settlement procedures.”

This example illustrates how, even at this early stage, the Philippines has benefited from seeking an independent and authoritative perspective, which allows us and all members of the observing international community to move beyond listening to any country’s simple say-so.

Equalizer

Without a fair third-party perspective, such deadlocks might simply go the way of Panatag Shoal, with the weaker party enduring months of armed or diplomatic intimidation it is poorly positioned to withstand.

In this light, we appreciate Foreign Secretary Albert del Rosario’s words in last month’s Foreign Policy magazine: “At the end of the day, we really think international law is the great equalizer.”

Nine-dash line

The tribunal will not award sovereignty, which is beyond its remit and not included in our submissions for this reason. However, having determined jurisdiction, the court can now examine the basis on which China claims sovereignty over the entire South China Sea (the area within the “nine-dash line”) hinges.

Of course, it is a risk. Thankfully, our legal minds say our case is strong. By submitting to the process, the Philippines can acknowledge its mistrust but nevertheless move beyond it toward fairly determining a concrete basis from which to proceed.

Naysayers may counter that any decision by the tribunal will be difficult, if not outright impossible, to enforce. In reality, eventual “enforcement” may take many forms. In the long run, the Philippines could need to negotiate with China, Malaysia and Vietnam to settle the issue.

Bargaining position

If and when this occurs, however, the country’s negotiators will have a much stronger bargaining position if an independent party has found that the preferred argument of the opposing side is invalid.

A future settlement in which the Philippines or any Southeast Asian country cedes its claims to China wholesale is made far less likely. If the tribunal upholds the nine-dash line, we are no worse off than now.

In relation to enforcement and in a second breakthrough, the United States sent the USS Lassen on Oct. 28 to sail within 22 km off Zamora Reef in the Spratlys.

Helipad

The reef is notable for having undergone dredging and reclamation by China since 2012. Zamora used to be underwater except at low tide; today it hosts a four-story building with weather and radar devices, a helipad and 200 soldiers.

China’s buildup is not only disconcerting because of its military aspects but also because of a suspicion that the transformation of Zamora and other underwater reefs into above-water concrete installations might prompt China to claim more maritime rights than the reef would otherwise be entitled to under the law of the sea convention.

Although this interpretation is not widely held among legal scholars, the possibility that China might do so and go unchallenged explains the importance of the Lassen sail-by.

Freedom of navigation

The sail-by is what the United States calls a freedom of navigation operation (Fonops) wherein its ships sail through waters claimed by any given country in cases where it considers these claims not in keeping with international law.

Underscoring this principle last month, US Defense Secretary Ashton Carter affirmed that the United States “will fly, sail and operate wherever the international law allows, as we do around the world.”

Fonops worldwide are routine for the US Navy but this Lassen move is the first from that country in this specific area since 2012.

Through the long-awaited operation, the US Navy provided a physical demonstration of the consensus legal opinion that the transformation of these reefs did not change their maritime entitlements.

In other words, China can do what it likes to Zamora Reef but the reef will not generate even 22 km of territorial waters. The operation is not intended to support any one country’s claim.

Lest the operation be interpreted as unfairly targeting China, we should note that the United States has also performed these operations in Philippine-claimed waters. The US defense department reports that it did so multiple times in 2014 alone.

Rustled feathers

As expected, the move rustled feathers in Beijing. Xinhua, China’s state-run news outlet, said the sailing would be “sabotaging regional peace and stability, and militarizing the waters.”

Filipinos should take heart that international support for arbitration and the rule of law in the South China Sea continues to increase and to manifest in the waters. As with the Philippine case at The Hague, such operations would send a strong signal that the South China Sea dispute is of broad international concern and that all countries should act in accordance with their agreed-upon commitments.

Looking forward, US officials have indicated that their Pacific Command is working on a plan to conduct similar operations from Subic or Clark. If true, these plans cannot be disentangled from the Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement (Edca) between the Philippines and the United States, which has been held up in the Supreme Court.

We hope for a ruling on Edca at the soonest possible time.

(Victor Andres Manhit is president of the Albert del Rosario Institute, an independent international and strategic research organization focused on the Philippines and East Asia.)