Why the Inquirer’s series of essays, commentaries and columns about the dark days of martial law 29 years after the Filipino people forced its end?

First of all, because “The Philippines and the Filipinos would never be the same since, and we who look back on those days tread the fine line between remembering and forgetting”—to borrow historian and Inquirer columnist Ambeth Ocampo’s take on martial law.

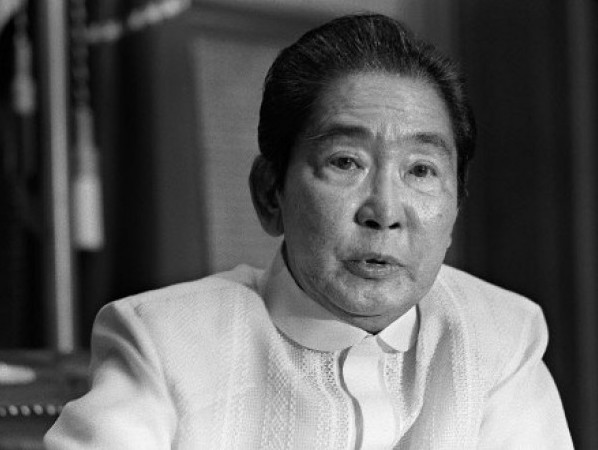

Secondly, because of the ill attempts at historical revisionism so evidently at play today. A galling example of such attempts Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. delivered in a reply to a question about martial law, during a talk show some weeks ago: “What am I to say sorry (for)?” In that same show, he also proposed that “recent political history” sees his father’s dictatorship in a more positive light, and that he often hears people saying things were better under the Marcoses. The statement, coupled with the idea that he is being pushed as a possible vice presidential candidate in the coming presidential election, sent chills down people’s spines.

Thirdly, as the Inquirer Research Staff noted in “Attention millennials: You ain’t seen nothing yet,” (Front Page, 9/20/15): The millennials, born between the 1980s and the 2000s, this generation composed of Filipinos between mid-teens and mid-thirties, the first to come of age in the new millennium, share “one other characteristic: None of them was around when the late dictator Ferdinand Marcos declared martial law in 1972, which was ‘lifted’ in 1981 but remained in force until Marcos was ousted from Malacañang in the history-changing bloodless Edsa People Power Revolution of February 1986.”

To be clear: Anyone who says life under the Marcoses was better either did not actually live through the terrors and horrors of martial law or, even worse, never understood what was going on. Martial law would always be a total, monstrous aberration from democracy, more so the kind Ferdinand the father clamped on the Philippines and wrapped with deceitful platitudes—and now is being resurrected by the son as a golden era.

It is important that the youth and those of us who may have forgotten or chosen to forget revisit those days, especially amid attempts by certain quarters to present the arrests, torture, killings, disappearances and other depravities of the dictatorship as if they were mere lies or figments of the imagination—especially now that those atrocities are in clear danger of being glossed over, particularly in the heat of the election season.

The good news is that others are taking up the fight against what could otherwise develop into an unfortunate national amnesia. Civil society groups, many led by those who suffered directly under the Marcos dictatorship, are speaking loudly against any kind of whitewashing of the Marcos sins.

At the University of the Philippines in Diliman, students re-enacted scenes of martial law with a run than remembered slain activist Leandro “Lean” Alejandro. “Memory is a tricky thing. This run is an act of remembering,” said Susan Villanueva, chair of the UP Samasa alumni. “We lived through the time and it is our moral imperative to pass on this lesson—that martial law was not the good old days.”

The art group Dakila, bothered by the sudden surge of “historical revisionism” and Marcos-era nostalgia, put up posters debunking the many sugar-coated lies about that era, point by point, such as its rebuking of the claim that the Philippines benefited from a robust economy. It also called attention to “[t]he price of fighting for freedom during the martial law years: 50,000 people arrested in the first three years, 3,257 murders, 35,000 torture cases, 70,000 incarcerations.”

To be sure, it is the youth who are the target of this rewriting of history. Luckily, the youth seem to be interested in history again. If this is any indication, the film “Heneral Luna” has whipped up an interest in one of the main figures of the Philippine-American War. A continuing education is necessary to keep generations connected to the past, and, most important, to push the continuing revolution—a revolution that can succeed only in the hearts and minds of young Filipinos and can happen only when they understand the suffering and enduring damage the Marcos dictatorship and martial law caused the Filipino nation and soul.

The hashtag #NeverAgain, a creation of the current times, raises a hopeful sign that the future will yet be in good hands.