Strategy for peace in our seas

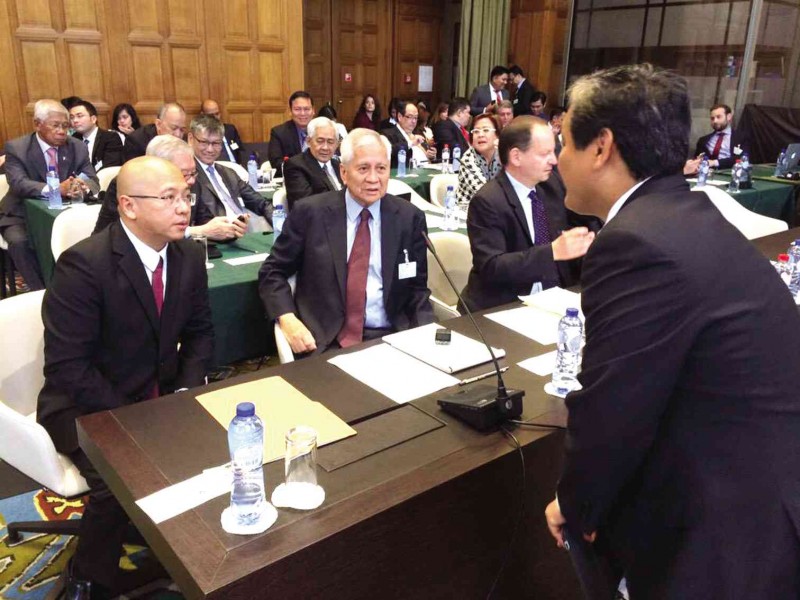

SOLICITOR General Florin Hilbay, Foreign Secretary Albert del Rosario and Philippine Ambassador to the Netherlands Vic Ledda at the Peace Palace in The Hague before the start of oral arguments on the Philippine case against China’s claims over the West Philippine Sea. PHOTOS FROM ABIGAIL VALTE’S TWITTER ACCOUNT/Permanent Court of Arbitration

The Naval and military buildup in our maritime heartland is a failure of diplomacy.

If war were to break out in the South China Sea, it would only be either America or China that would emerge as the genuine victor. Such a call will cast a shadow over hopes of a more robust and independent Philippine foreign policy. We shall not only lose effective control over our islands but also let the power of our destiny as an archipelagic nation slip from our hands.

Why are we being drawn into conflicts not of our own making? The admonition of Sun Tzu—“If you know neither the enemy nor yourself, you will succumb in every battle”—is instructive because it conceals a third element that is central to the knowledge that opponents will have of each other. How do we come to imagine who our enemies are—what is the object of our strife?

The South China Sea represents a complex scenario of three issues: the first is the contest for spheres of influence; the second is the competition of claims for sovereignty and the delimitation of maritime boundaries, which derive from land features; and finally, there is the “unseen” conflict between the human species and the seas and the oceans.

To see through the muddle, I shall treat each of them briefly and propose that we think of and experiment on a fresh solution.

3 major tensions

The first revolves around the stability that the United States and China seek in order to secure their national interests. The term “pivot,” which the United States has used to describe its rebalancing strategy in the Asia-Pacific, maintains its central dominance as a power that turns around to wherever there are threat and opportunity, and China in its eyes oscillates between these two ends.

China sees the world primarily as a network through which goods, services, capital and people can flow and expand in a global economy. It is steadily consolidating a multinational development strategy to spur trade and investment that includes the establishment of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the New Development Bank of the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa).

Between these two global powers—one waning and the other wanting more—the South China Sea is a coveted millennial route between the East China Sea and the Eastern Mediterranean, connecting economic dynamos, like India and Indonesia, and valuable sources of energy and raw materials, including not only liquefied natural gas, coal and iron ore, but also crude oil from Africa and the Persian Gulf.

The grand military strategies that arise, invented to keep these lanes of communication free and secure, can thus easily throw the Philippines off course. We risk stopping short of our preferences (e.g. a sustainable maritime environment) and settle for one of many outcomes (e.g. a presumably well-equipped Navy).

We become the undiscerning recipient of side payments, the basket of a burgeoning regional defense equipment industry

—and end up inadvertently taking sides in a theater of conflict.

The second scenario is a conundrum: Who owns which of what? There are fundamentally three contested areas in this sea—Scarborough Shoal and two archipelagos called the “Paracels” and the “Spratlys,” which comprise islands, rocks and low-tide elevations. The Spratlys has the biggest number of parties (six) that contest sovereignty on either historical or legal grounds.

Arbitration

The Philippines, in line with the Department of Foreign Affairs’ Triple Action Plan, identified “arbitration” under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (Unclos) as the “final approach” and the “enduring resolution” in the settlement of the dispute. Unclos establishes a universal standard for maritime zones over which states may exercise their rights and responsibilities, thus according primacy to international law over historical assertions.

China has rejected the plan and has refused to participate in the proceedings of the International Arbitral Tribunal in The Hague. The case is complex. Fundamentally, the Philippines seeks a ruling on maritime rights and entitlements—not on the question of sovereignty. China contends in a separate position paper, however, that unless sovereignty is resolved, rights and settlements will remain undetermined.

The problem here is not that neither of the parties has put forth an untenable argument but that they are starting from two assumptions each of which pertains to a discrete institutional arrangement (i.e. Unclos, in any case, was not designed to adjudicate sovereignty), and that, in the event, the grounds for questioning these assumptions require geopolitical considerations.

The Philippines does not do bad in pursuing relief from the fuzziness of zone jurisdictions but the process prompts us, just as well, to the inchoateness of international law and the intransigencies of states in pursuit of power.

The third scenario turns on the silent death of the sea.

The alarm bells sounded off by National Scientist Dr. Edgardo Gomez, has alerted us to the annual loss of $281 million because of the destruction of the coral reef ecosystem in the South China Sea. If we add to this two more reported scientific facts on the state of our oceans—one, its already strained absorptive capacity due to carbon emissions, and two, a “postwar technology” that has driven global fishing from an annual average of 15 million metric tons at the end of World War II to 85 million metric tons today—the reality can leave us mute.

There is an Italian saying that we are all under one sky. Are we not, I ask myself, all above one ocean?

How to end a dispute

The Philippine stand on the South China Sea ought to be articulated on a wide but rational and adaptive policy agenda. I concede that the three scenarios above are not necessarily mutually exclusive but this is exactly where leadership can transform. It is by linking them strategically that we can command as an independent country and guard ourselves against confusion and the impairment of the political imagination.

In the long term, we need a stable maritime infrastructure in the South China Sea—an international regime—defined as a set of principles, norms and decision-making procedures around which member-states’ expectations may converge.

Consider the valuable precedent of the 1976 Convention for the Protection of the Mediterranean Sea Against Pollution. We, too, can creatively craft our own say on any of the following, in no particular order: the conservation and sustainable use of marine biological diversity, maritime security or the freedom of navigation.

In the medium term, we must work toward a regional agreement—a subregime—primarily, I believe, on the common stewardship of the Spratly Islands. The “threat” between China and the United States, and, depending on how they posture, the threat that they pose together, as we proceed to define our broader interests in the world, may and ought to be distinguished from the more practical aspects of how to behave in an area of competing claims.

Should this experiment succeed, we then derive a model on which variations can be made for the effective administration of the remaining islands and disparate land features, and from which rules and procedures can gradually be negotiated, including, if desired, more complex regional arrangements, such as humanitarian relief in natural disasters.

New institutional process

In the immediate term, the symbols of belligerence on our shores demand that a new institutional process be launched with diplomatic discretion and without delay. What does this initial step entail?

A fresh round of high-level consultations between the six claimant states.

The specification of a new zone of agreement and the formation of a coalition.

The establishment of an intergovernmental committee that will monitor and report on all agreed activities in the Spratly Islands.

The distinctive and principal features between this three-tier strategy toward an international regime and the on-going negotiations between the 10 members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean) and China on the implementation of the 2002 Declaration on the Code of Conduct in the South China Sea cannot be overstated.

‘Coalition of 6’

Six is the mathematical key. It represents China, Brunei, Malaysia, Vietnam, Taiwan and the Philippines—countries that have competing claims in the Spratlys. This feature holds that membership to the coalition and the subregime be circumscribed to direct stakeholders.

Nonclaimants will tend to skew the zone of agreement and alter the variables in the creation of a regime: the configurations of power, individual and collective interest, and the intersubjective knowledge of the negotiators and the governments they represent at the table.

Secondly, while the Asean-China negotiations are presumed to be on course, Chinese reclamations totaling at least 800 hectares show the disparity between the facts on the ground and the rhetoric on the intentions to preserve the “status quo.”

Indeed, the execution of the declaration itself has been marred because of the incursions and standoffs, which have periodically taken place between parties since 2002. How can a code of conduct be agreed upon legitimately if it is based on features which are constantly shifting?

A trust deficit has accrued. Parties must deliberate on zones of agreement (e.g. fishing activity, resource development, transit or movement of vessels) and their permissible levels of exercise, or else simply put a halt to it. These will be determined on the premise that a neutral compliance mechanism will be put in place to report on future deviations in the clearest, most transparent and objective way possible.

Razor’s edge

The third feature is what I call the razor’s edge: two oppositional forces that produce vitality in regime formation.

On one side I see the existence of a “transcendental interest” (a concept denoted by the political theorist Otfried Höffe), which refers to “interests that are necessary in the sense that they are not a matter of choice to an actor but must be pursued and protected if the actor is to pursue any interest at all.”

In this respect, our geography binds us as littoral states around the same sea—upon it our economies have flourished and we have sailed across her waters in all directions, interconnecting our peoples in prosperity over centuries. By protecting this unique ecosystem, we safeguard the well-being of our communities and future generations.

Furthermore, by negotiating the terms of its lawful enjoyment, we secure the survival of the state and our status as equal sovereigns.

On the other side is the “veil of uncertainty” (denoted by constitutional theorists Geoffrey Brennan and James Buchanan). The fact that institutional arrangements apply across a variety of contexts and over an extended period, “both the generality and permanence of rules are increased, (and) the individual who faces choice alternatives becomes more uncertain about the effects of alternatives on his own position.”

The scholar Oran Young supports the contention that such uncertainty “actually facilitates efforts to reach agreement on the substantive provisions of international regimes.” Observe, therefore, the list of areas for the institutional design of a cooperation framework.

What do the six countries agree on?

Environmental regimes

Unclos

Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora

Convention on Biological Diversity

Multilateral trade and security fora

Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (Apec)

Asean Regional Forum

Summitry

Asean+3 (China, South Korea and Japan)

East Asia Summit (EAS)

Earth Summits (“Rio Summits” 1992, 2002 and 2012) are the UN conferences from which the “global green agenda” have evolved.

It is important to note that neither China nor any of the disputants recognize Taiwan as a sovereign state but stakeholder participation is crucial for winning as wide a consensus as possible. Taiwan is not a signatory to these conventions but participates in Apec and the EAS.

By restoring the centrality of the six states and by pursuing high-level consultations across a selection of extant regimes, international fora and summitries, and issues, the zone of agreement will be sensitive to national interests, realistically embedded within evolving debates in international politics and will appeal to commonly held values and beliefs. We move away from preponderance and come closer to what we might call a Coalition of 6 Principled States (6 COPS) on the South China Sea.

Coming of age

Why are we ready to test such a proposition?

First, because war is an unlikely possibility; it will not stand between America and China and the benefits of a strategic economic and security deal. If there is a trait that goes beyond the pale of their modern ideologies, it is a sense of practicality, not to mention a hardy belief in the power of markets.

An arms race in this day and age does not sound right, especially in a region that is young, vibrant and is building a community to bridge Cold War divisions.

Secondly, the Philippines is more equipped than at any other time in its history to lead. We are among fastest-growing economies in Asia and Supertyphoon “Yolanda” (international name: Haiyan) has shown to the world that we are a resilient people. If the country is united in the South, then we will also have demonstrated to ourselves that we are maturing into political sophistication.

Finally, we are allies with America, a good neighbor to China and a founding member of Asean. Our relationships with them can be equidistantly unique. It is time to unfasten the leash of colonial consciousness and take pride in our own identity as a nation.

Collective good

There is a sad irony about our scramble over the South China Sea when you discover the practice of local fishermen, whose families have been fishing these paradisiacal grounds for generations. As they cross waterways with other folk, the bounty is shared unsparingly with those who come home on empty baskets.

This sea, which is the object of our strife, is a collective good. Those of us afar fail to see that there are no fences. Building them now together may seem an enterprise far less gallant. But casting the net on the other side of the boat may be our best chance for keeping the peace. The catch is not to discover who the good neighbors are but what it is that makes us good neighbors.

(Kevin H.R. Villanueva is a senior research advisor at HZB School of International Relations [Philippine Women’s University] and director of the think tank ARiSE. He holds a master of science in International Relations from the London School of Economics and a Ph.D. in International Politics from the University of Leeds [UK].)

For comprehensive coverage, in-depth analysis, visit our special page for West Philippine Sea updates. Stay informed with articles, videos, and expert opinions.