Opposition to the Aquino administration’s flagship education program has snowballed, leading not only to protests but also to five petitions in the Supreme Court against Republic Act No. 10533 or the K-to-12 (kindergarten to Grade 12) law.

With the Department of Education (DepEd) and the administration largely dismissing criticisms against the K-to-12 program, it is high time to elevate the discourse on the program’s real impact on students, teachers and even workers.

K-12 ready?

Perhaps, the most discussed pitfall of the K-to-12 program is the government’s ill-preparedness for the full-blown implementation of the curriculum.

Despite the annual increases in the budget for school buildings, the administration has yet to close the classroom gap. At the beginning of the Aquino presidency, his administration stated in the Philippine Development Plan (PDP) 2011-2016 that the country lacked an estimated 113,000 classrooms.

However, in the updated PDP published in 2014, DepEd reported that only 66,813 classrooms had been constructed since 2010. Curiously, the government also reduced the classroom backlog estimate from 113,000 to only 66,800 in an apparent attempt to hide the underperformance.

As it stands, the administration has been able to meet only about 60 percent of the total classroom backlog stated in the original PDP. However, as the K-to-12 program introduces two additional years of senior high school, the shortage could only go higher.

More classrooms needed

In its latest report to Congress, DepEd states that every additional year in the basic education system requires 20,000 to 28,000 public classrooms, translating to a 40,000-56,000 additional classroom shortage for the two-year Senior High School (SHS) program. As a result, the official classroom shortage, including the requirements for the K-to-12 program, will reach over 95,000.

DepEd says the implementation of the SHS program will also require an additional 60,000 to 82,000 teachers. The K-to-12 program also requires the printing of a minimum of 60 million textbooks, since textbooks designed for the previous 10-year curriculum will be rendered obsolete.

Given the fact that the annual basic education budget has never reached 4 percent of the country’s gross domestic product, much less the global standard of 6 percent, there is a high probability that the shortages will go from bad to worse after the full rollout of the K-to-12 program.

While these shortages and lack of preparation are enough to cause alarm, there are still more pernicious aspects of the program that need to be addressed.

Downward spiral

The main argument of the proponents of the program is that adding two years to the basic education curriculum will vastly improve the performance and competency of Filipino students and make Philippine basic education at par with international standards.

However, such argument was never proven by quantitative research. On the contrary, in a study authored by UP professor Abraham Felipe and Fund for Assistance to Private Education executive director Carolina Porio, titled “Length of School Cycle and the Quality of Education,” it was shown that there was “no basis to expect that lengthening the educational cycle calendar-wise, will improve the quality of education.”

While the K-to-12 program implements a “spiral progression approach” to teaching, wherein subjects are intended to be taught in a manner of increasing complexity, initial observations show that the new curriculum is rather redundant and overall focus on basic concepts is largely diffused.

In chemistry, for example, the concept of the atom is introduced belatedly in Grade 8. This is in stark contrast with the curricula in countries, like Singapore or Germany, where the concept is taught in earlier grade levels.

The quality of instruction under K-to-12 program is also far from being assured. With the severe lack of facilities and teachers, the practice of shorter hours of instruction is set to continue.

Nationalists also decry the elimination of important aspects of Philippine history, literature, culture and government in the K-to-12 curriculum. In fact, Philippine history is absent in both junior and senior high school courses. To add insult to injury, even the social studies curriculum is derived from topics created by the US National Council for Social Studies.

Impact on labor

According to research think tank Ibon Foundation, the country deployed 4,500 workers abroad per day in 2014, far outpacing its 2,800 average daily job creation domestically. This situation will undoubtedly worsen under the K-to-12 program, as it clearly aims to produce graduates that are readily employable by foreign companies that seek cheap labor.

Four career tracks

The specialized curriculum for the SHS program has four career tracks that students of Grades 11 and 12 can enroll in. These are the academic, arts and design, sports and technical-vocational-livelihood (TVL) tracks.

In its “Basic Education Midterm Report” to Congress in March, DepEd said it planned to put 32,000 or

1.4 percent of incoming SHS students under the sports track and another 32,000 under the arts and design track.

A total of 609,000 or 49.7 percent of incoming SHS students are set to take the academic track, while 596,000 or 48.7 percent of the students are bound to pursue the TVL track.

The large proportion of students that DepEd aims to enroll under the TVL track is in line with its aim to produce more skilled workers and is, in fact, engineered to serve the government’s labor export policy. This is apparent in the way the TVL curriculum is designed to respond to the current demand of the international labor market for skilled workers.

International market

Aligning the basic education curriculum to the demands of the international market is problematic as the so-called “in-demand” jobs are more often than not temporary and subject to the rise and fall of global demand. Take for instance the sudden boom—and subsequent bust—of the demand for nurses abroad.

Ultimately, the K-to-12 program is designed to push students to leave formal education early and not pursue college. In effect, the government is bringing down the age of the employable pool.

With more high school students dropping out before finishing high school or choosing to join the workforce directly after Grade 12, more workers will soon be competing for scarce jobs, bloating the ranks of the unemployed.

Such a scenario will result in the gradual lowering of wages as job competition will allow both local and foreign employers to forcibly introduce lower wage rates.

Additional costs

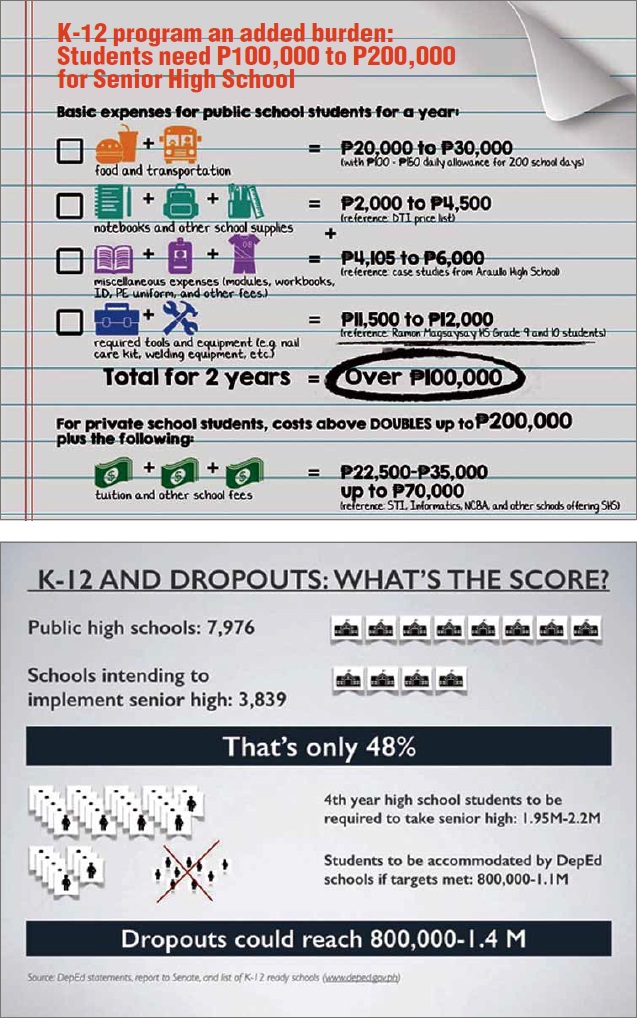

Adding two years to the basic education curriculum entails additional costs for students and their families. It is estimated that a senior high school student in a public school will need to shell out roughly P100,000 to cover expenses for the additional two years. A student in a private high school will need double that amount, or P200,000.

The burden of the K-to-12 program on students does not stop there. Data from DepEd show that the SHS rollout is designed to force more students to enroll in private schools.

While DepEd estimates that up to 2 million students will enter senior high school come 2016, it has reported to Congress that the country’s public school system can accommodate only 800,000 to 1.1 million senior high school students.

DepEd expects that the remaining 800,000 to 1 million students will be absorbed by “non-DepEd schools,” which are composed of state colleges and private education institutions.

In Metro Manila, only 43 out of 247 public high schools submitted budget proposals for senior high. Meanwhile, DepEd gave 287 private high schools and private higher educational institutions in the metropolis the permission to offer senior high. There are even cities, including Caloocan, Makati, Parañaque and San Juan, where no public high school has signified an intention to offer senior high school.

Due to the incapacity of public schools to accept all incoming senior high school students, many are faced with two options: enroll in more expensive private schools or drop out.

Voucher system

DepEd argues that this is the reason it is pushing for the SHS “voucher system” in which students who will be pushed out of public schools can opt for a tuition subsidy, ranging from P8,750 to P22,000.

What DepEd doesn’t emphasize, however, is that the voucher—even at its highest range—is not enough to cover the matriculation of most private high schools at present, where tuition ranges from P35,000 to P70,000 a year.

Layoffs

Teachers are not exempt from the scourge of the K-to-12 program. Since higher education institutions expect up to zero enrollment following the full implementation of SHS, many colleges and universities are starting to lay off teachers and employees.

The worst-case scenario reported by DepEd shows that about 90 percent of permanent faculty members who teach only general education courses would be retrenched. Also facing retrenchment are 30 percent of permanent employees and virtually all nonteaching contractual staff.

All in all, DepEd estimates that 25,000 to 78,000 teaching and nonteaching college personnel would be retrenched due to the program.

To mitigate the impact on labor of the K-to-12 program, DepEd plans to rehire displaced college teaching staff as basic education teachers. But there’s a catch: the college teachers to be rehired under the DepEd mitigation program will experience a “diminution” in salaries, with some losing as much as half of their former salaries. Current college faculty salary ranges from P21,000 to P41,000 a month, whereas the entry-level pay for Teacher II position under DepEd is only P19,940.

Corporations

DepEd designed the implementation of SHS in a manner that will guarantee higher enrollment in private institutions and, consequently, greater profit for school owners. Through the voucher system alone, DepEd is set to give P13.2 billion to P19.8 billion in profits to private school owners. This comes at a time when such private schools enjoy maximum leeway in increasing tuition and other school fees.

With billions in public funding virtually waiting at the doorstep, large corporations, including STI Education Systems, Informatics Holdings Philippines and Ayala Corp. recently established “Apec [affordable, private, education center] schools” in partnership with United Kingdom-based Pearson Group. They immediately tied up with DepEd for the implementation of the voucher system.

Additional years of schooling may, in the first instance, sound good. Yet, solving the crisis of education does not merely entail adding two years of education. The approach should be a combination of national interest, scientific analysis and sound policy judgment that is not hinged on profit or reaching global standards, but is imbued with a high sense of public duty.

After all, basic education is neither a business enterprise nor a privilege. It is a constitutional right that must be upheld by the State.

(Marjohara Tucay is the executive vice president of Kabataan party-list and convenor of the Stop K-to-12 Alliance, a broad formation of youth groups and education advocates campaigning for the junking of the K-to-12 program.)