Losing ground in war vs poverty

Last week, we focused on the good news: The Philippines is finally making progress in the war against corruption. The basis for that statement is the improvement of the country’s rating in the Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) of Transparency International. The Philippines moved from the bottom quarter to the top half between 2010 and 2014. That is nothing to sneeze at.

Yes, we still have a long way to go. But considering that between 1995 and 2010 our CPI even worsened—from 2.8 to 2.4 (in 15 years!)—that jump in the past four years (we are now at 38; they now score from 0 to 100), is definitely a feather in our cap.

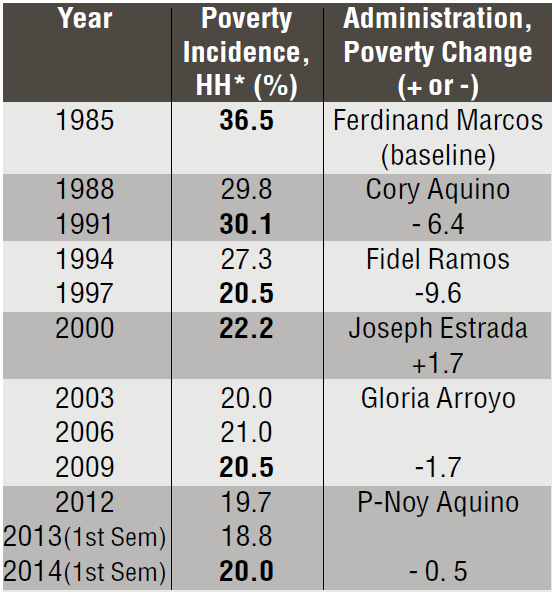

So what’s the bad news? That the Philippines is apparently losing ground in its war against poverty. The basis for this can be seen in the table, which traces the poverty incidence of households in the Philippines since 1985.

*1985-1997 Fixed Level of Living Estimates computed by Arsenio Balisacan. From 2000 onward, estimates by NSCB—very similar to Balisacan estimates. Based on Family Income and Expenditures Survey, conducted triennially.

The table shows that between 1985 and 1997, the Philippines reduced poverty incidence by 16 percentage points, from 36.5 percent to 20.5 percent. That is a fantastic performance, attributable to Cory Aquino (6.4 percentage-point reduction) and Fidel Ramos (9.6 percentage-point reduction). This 12-year period is what I have called the Success Phase in our poverty reduction efforts.

Notice that Cory Aquino’s battle against poverty resulted in a poverty-incidence reduction of 6.7 percentage points by 1988. But the repeated coup attempts against her regime and the US recession of 1990-1991 took their toll. And poverty incidence rose, rather than fell, after 1988, by 0.3 percentage points. The Ramos administration had no coup attempts and no economic shocks except the Asian Crisis, which occurred in the last year of his term (mid-1997 up to start of 1998). The effects were felt more by his successor. He can rightfully boast that his term resulted in the largest reduction of poverty incidence: 9.6 percentage points. I repeat: a fantastic performance.

If this performance had been repeated in the succeeding 12 years, from 1997 to 2009, our poverty incidence would have been reduced to 4.5 percent of households, and we would have more than met the Millennium Development Goal against poverty. Instead, look what our table shows us: Poverty incidence remained at 20.5 percent in 2009.

In other words, the best thing that can be said about our antipoverty performance since 1997 is that it foundered. Look at 1997: 20.5-percent poverty incidence. Now look at 2009: 20.5-percent poverty incidence. No movement, despite the lapse of 12 years. Compare this with the 16 percentage-point decrease in poverty incidence during the previous 12 years. Which is why I call the period after 1997 the Failure Phase of our war against poverty.

Actually, as the table shows, poverty incidence didn’t remain constant during that period. It rose by 1.7 percentage points by 2000, which coincided with the incumbency of Joseph Estrada (whose campaign slogan, ironically, was “Erap Para sa Mahirap”). But remember, it was Estrada who had to deal with the aftermath of the Asian Crisis.

Gloria Arroyo took over from Estrada, and it took her nine years to reverse that 1.7 percentage-point increase that was the legacy of her predecessor (more accurately, she reversed it in the first three years, but poverty increased again, and then decreased). Think of it, Reader. Against what Cory Aquino did in six years (poverty reduced by 6.4 percent) and what Ramos did in six years (poverty reduced by 9.6 percent), Arroyo in nine years reduced poverty by 1.7 percent.

So we come to the P-Noy administration. What we can say is that P-Noy wanted to make sure that we could measure poverty more frequently than once every three years. So we have had estimates of poverty every year since 2012. And what does it show us? That since 2009, poverty has gone down by 0.5 percent. That’s P-Noy. Compare that with his mother’s antipoverty performance.

All is not lost, however. What the Philippines has now going for it in the war against poverty is the Conditional Cash Transfer program, started by Arroyo and expanded by P-Noy. That program is aimed at destroying the intergenerational transfer of poverty by making sure that children in a poor family have the chance to finish a high school education and to be healthy. The benefits will be felt in the long term, but it will be felt. P-Noy could have used that money to improve the poverty incidence figures during his term, but he chose to be a statesman rather than a politician. That much we must give him. That much he deserves.