Reactivate public spaces in UP Diliman

She was quietly slumped in a corner of the makeshift library on top of a tree, a book resting on her outstretched knees. “Honesty Library” is the sign on a plywood, leading to a learning space collaboratively done with some campus workers in the University of the Philippines Diliman in Quezon City and residents on C.P. Garcia Avenue.

“Ate, anong magandang basahin? (which one is a good read?)” she would ask, pointing at the stack of donated books and displaying her eagerness to read, although she would later admit that her favorite subject is Math.

Ten-year-old Tisay lives on C.P. Garcia with her family. Her father works as a security guard in UP, the reason she treats the university as her comfort zone.

“Gusto ko rin mag-aral sa UP para maging teacher ng Math (I also want to study in UP to become a Math teacher),” said Tisay, an incoming fifth grader at Krus na Ligas Elementary School.

Tisay and other children belonging to the 70,000 informal settlers in communities within UP Diliman now treat the UP old stud farm as a place where they are no longer tagged as “informal,” and where they can understand the value of space and coexistence in the state university that once claimed to be a community for all.

Off Site/Out of Sight, a project initiated by two independent artists, saw the potential of this abandoned piece of UP land. They wondered how the pamantasan ng bayan had become home to conflicts related to site, resources and webbed relationships.

‘Invisibles’

The 493-hectare land of UP Diliman displays a contrast between “developed” and “informal” sites, which poses yet another question to UP’s public character.

The campus covers eight barangays: UP Campus, Krus na Ligas, San Vicente, Botocan, Culiat, Old Capitol Site, Pansol and Vasra. Within these areas are at least 28 informal communities.

The 2011 Census of Self-Built Units (SBUs), conducted by the Office of Community Relations, found 4,961 SBUs, or households constructed without permits from the university administration. The SBUs had a total population of 21,578 individuals in Barangay UP Campus, the biggest barangay inside UP Diliman.

This figure alone was almost as big as the student population of UP in 2011, which was 24,395, according to UP vice chancellor for community affairs Nestor Castro.

The campus also employs more than 1,500 full-time faculty members, 1,700 academic personnel and over 1,600 nonacademic personnel.

The census also revealed the presence of at least 15,500 households living in SBUs, with an average of 4.5 members in every household.

The 2004 UP Campus Informal Settlements Map by Florence A. Galeon estimated that 16 percent of UP Diliman’s total land area, or roughly 79 hectares, may be labeled informal settlements.

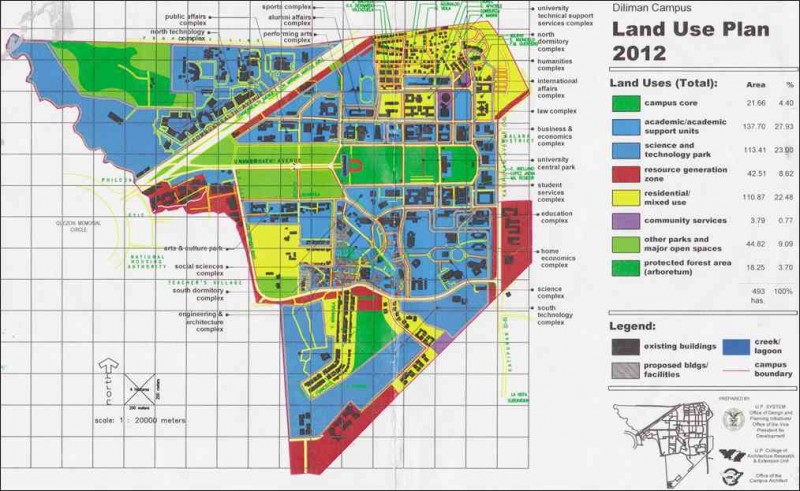

Land use plan

But even if they outnumber members of the academic community, they are still easy to be dismissed to invisibility because both the 1994 and 2012 UP land use plans do not specifically involve provisions on handling their settlements.

Under the current land use plan approved by the Board of Regents (BOR) in 2011, intended uses of UP land include campus core (21.66 hectares), academic/academic support units (137.70 ha), science and technology park (113.41 ha), resources generation zone (42.51 ha), faculty and staff housing (95.18 ha), dormitories (15.69 ha), community services (3.79 ha), parks and open spaces (44.82 ha) and protected forest area (18.25 ha).

Castro said the provision for residential areas did not distinguish legitimate UP personnel from informal settlers.

Conundrum

Here lies the conundrum on UP land: How can the campus administration serve the needs of its academic community without leaving thousands of residents homeless? Where do stakeholders draw the line between UP as a public space and as an academic space?

Claro Ramirez and UP Art Studies assistant professor Eileen Legaspi-Ramirez of Back to Square 1, an independent art platform, thought of how they could use art as a means to create a common ground on campus that would spark discourses on public spaces, people and the contexts that bind them.

Veer from mall concept

“The idea is to veer from the ‘new mall, new parking lot’ concept that seems to prevail in present society because that concept doesn’t really solve the problems that we have. We’re looking at them the wrong way,” Claro said.

These problems in communities, according to him, involve succumbing to a sanitized, lifeless urban space and eliminating those whose living conditions are “informal” from the urban planning process.

“We can’t make them (the informal settlers) invisible. We cannot disregard them,” he said.

Being virtually at the center of a core of informal settler communities, the two curators thought that the former stud farm could be a perfect metaphor for the “invisibility” that characterizes UP’s ecosocial and biocultural systems.

The former stud farm, formally called the National Stud Farm back then, was established through Republic Act No. 4618 on June 19, 1965, during the administration of former President Ferdinand Marcos.

From horses to dump

The four-hectare National Stud Farm was set up to improve the breed of Philippine horses for the benefit of all breeders and horse owners, and to prevent illegal importation of race horses.

Activities at the old stud farm declined in the aftermath of Marcos’ ouster in 1986 until its personnel, programs and resources were formally integrated into the Department of Agriculture in 2000. In 2003, its functions were reassigned to the Philippine Racing Commission.

Consequently, the horses were replaced by piles of solid and yard waste from UP and rubble from Quezon City Hall, as the place houses the materials recovery facility of the campus.

Implementing the Off Site/Out of Sight project on a dump is a difficult challenge according to Claro because his group literally had to start from zero.

With the help of local artists, students, UP staff and volunteers from nearby communities, Off Site/Out of Sight responded to the challenge by creating architectural elements, installations, community mapping and open-air structures using mostly materials (scraps, stones, recyclables, etc.) found on the ground, even cleaning and rehabilitating the site on their town.

“This is an informal project with informal artists and informal people,” Claro said. He suggested that the residents in informal settlements be called “formal settlers” in an “informal setting.”

Collaborative art

Off Site/Out of Sight counts on the mediating capacity of collaborative art in spaces of contention, where mutuality can exist among different groups.

This collaboration was best seen when the kids lent their tiny hands during cleanups, helped set up the stables, painted their own art pieces and assisted artists in creating installations, which were made from their own stories.

To further establish interaction with the communities, Off Site/Out of Sight employed two modalities: traditional and immersion.

In the traditional route, artists are matched to sites within the stud farm to produce installations addressing social and physical spaces.

“Model Units 1 and 2” by Jose John Santos III, Pam Yan Santos, Arvi Fetalvero, Ioannis Sicuya and Angel Ulama, play on the irony of “having a liveable space in the absence of access to land,” using typhoon debris from the farm and a nearby art school as materials.

It challenges the image of an urban Philippines made of homogenous condominiums, which offer substitutes for “nature” but anesthetize buyers from the actual state of spaces being transformed into “developments.”

The second modality, immersion, requires artists to work with willing households within clusters, such as Areas 1, 2, 3, 5, 11, 14, 17, Krus na Ligas, San Vicente, Pook Libis, Ricarte Palaris, Dagohoy, Aguinaldo, Amorsolo, Old Capitol, Botocan and the Arboretum for six months to demonstrate conditions on the ground, which are bound by competing interests in land and parallel resources, such as clean water and food.

Alma Quinto’s room-sized project “C.P. Garcia Homes: Build at Your Own Risk” serves as a parody of a gated community. Quinto, along with willing households, recreated community maps by allowing residents of C.P. Garcia to draw their homes on Manila paper during a workshop. It was both a cathartic and assertive exercise for some of their homes are set to be demolished.

UP as public space

How does UP define itself as a “community?” Are terms such as exclusivity, ownership and marketability part of its definition?

While commercial establishments have sprung on university grounds, at the fringes are the informal settlers. Some of them have been living in UP for decades even before the 1994 UP Land Use Plan was crafted.

“Informal settlers want to be relocated within the 493-hectare property of UP Diliman. UP, however, is seeking the assistance of the local government of Quezon City in looking for relocation sites outside of UP,” Castro said.

He said while there were no designated permanent relocation sites within UP, it was the university’s responsibility to ensure recognition of informal settlers who were employees of UP.

Containment, master plan

“The present policy of UP is that of containment … how to prevent the entry of new informal settlers. Thus, there is a Task Force on Squatting, Community and Housing Utilities that demolishes newly built structures. Those that are covered by the 2011 census are not affected,” Castro said.

The BOR’s passage of a system-wide UP Master Plan (UPMP) last year also raises a question about the black-and-white intepretation of UP land use, which informal settlers fear may result in evictions.

The UPMP aims to “assist in the understanding of the intentions of the various land-use zoning for all University of the Philippines real estate properties.” It also requires the creation of individual master plans for each UP campus following specific guiding principles and strategies for their development.

The master plan is to be finalized by the end of this year.

In 2013, UP president Alfredo Pascual said UP would develop its existing properties so it could generate additional resources—a means employed to cover for the insufficient budget being allocated by the government to UP.

Commercial zones

Being more open to commercial zones may also result in the transformation of the campus landscape. A recent example is the relocation of the UP Integrated School to give way to UP Town Center, an Ayala project within the campus after the UP-Ayala Technohub.

Entry to the campus grounds remains open to the public but the real contention ensued when the UP administration began to treat the growing population of informal settlers as a security and development threat to the academic community.

According to Claro, the presumption to outrightly treat the informal settlers as threats runs counter to one’s responsibility to educate them.

CHILDREN from nearby communities pose at the branched-out reading area of Claro Ramirez’s Honesty Library. Photos by Claro Ramirez/CONTRIBUTOR

Engaging stakeholders

From being a dump to a hub for tackling not only creative problems but also complex issues of territoriality is how the project aims to transform the forgotten piece of land.

“[The old stud farm] continues to be an active space with new work being done daily/weekly and collaborative workshops being hosted at various spaces within the farm,” Eileen said.

She said the team had secured a clearance from the university administration to start the second phase of the project—exploring the reuse of other materials in UP’s storage facilities. The team is also deliberating proposals for further collaboration with organizations.

“The key to phase two is further sharpening how we might make this sustainable not just logistically but more importantly in terms of getting stakeholders like the nearby communities of C.P. Garcia, Krus na Ligas and possibly even farther out, like Amorsolo and the Arboretum, to weigh in on how they may wish this venture to take shape in ways that are meaningful enough for them to continue the work [we] started,” she said.

After all, the project doesn’t only aim to engage UP. The group is also urging local governments to reflect on their urban planning choices, instead of channeling funds from the people to cosmetic solutions.

493 ha Land area of UP Diliman

24,395 Student population (2011)

70,000 Informal settlers (2011)

8 Barangays on campus

4,961 Self-built units (SBUs) in Barangay UP Campus without permit

21,578 People in SBUs

28 Informal communities