Tax reform for inclusive growth

While taxpayers perfunctorily prepare for the filing of income tax returns to meet the deadline on April 15, they hope for changes in our intricate, burdensome and outdated income tax system.

It has been almost two decades since the income tax structure was last revisited. Since then, salaries and wages have gone up, pushing more workers into higher income tax brackets. Inflation has likewise increased, putting a dent on the workers’ purchasing power. Thus, no matter their hard toil, workers still receive a sizable cut from their salaries and wages every payday for income taxes.

Article continues after this advertisementOver the past months, debates on income tax reform have intensified, with 17 pending bills in the House of Representatives and the Senate and with a likely headway in legislation before the year ends.

We provide a lowdown of this issue by analyzing data from various national surveys.

Things to know about our current tax system:

Article continues after this advertisementThe 85-16 problem

There were over 22 million wage and salary workers in 2013, according to the Labor Force Survey. These included all rank-and-file workers and officials in government (e.g., teachers, soldiers and Cabinet Secretaries) and in private establishments (e.g., clerks, janitors, security guards, messengers, managers and CEOs).

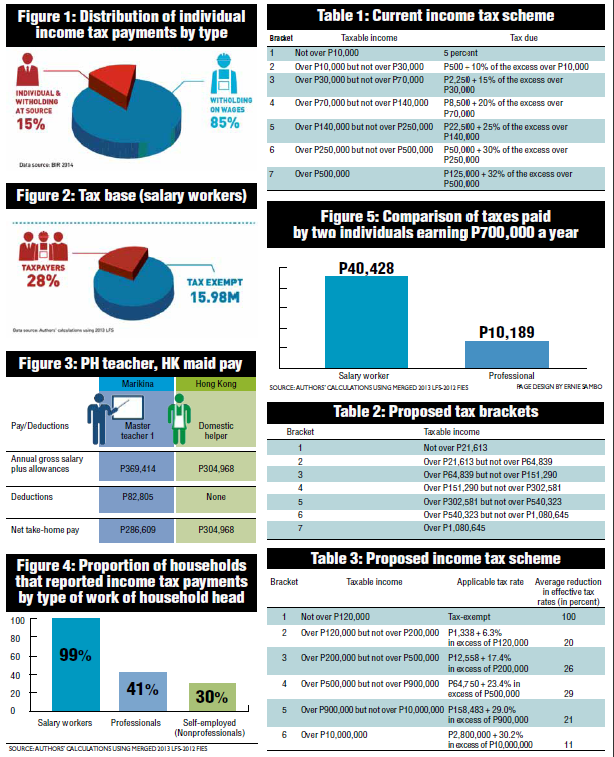

Salary workers have very little discretion on the amount of taxes they pay since these are automatically deducted from each pay slip they receive. Salary workers happen to pay the bulk of all individual income tax payments in the Philippines. In 2013, they paid 85 percent of the close to P236 billion collected by the Bureau of Internal Revenue (BIR). The remaining 15 percent were shouldered by professionals (e.g., lawyers, doctors, accountants) and the self-employed (entrepreneurs, store owners). (See Figure 1.)

Considering that 72 percent of salary workers consist of tax-exempt minimum wage earners (See Figure 2.), in reality only a small minority of all Filipino workers—16 percent—shoulder 85 percent of all individual income tax payments. In sum, only 6.3 million workers pay for almost all of the income tax payments being collected by the BIR!

Asian giant taxman

Our income tax rates are certainly the highest in Asia. The Tax Management Association of the Philippines has determined that for an annual income of P500,000, our tax rate of 32 percent is the highest among members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean).

In Hong Kong, the standard income tax rate is 15 percent, which is applied to net total income. Having one of the highest tax rates in the region makes the country uncompetitive with our neighbors and causes outward labor migration.

Teacher Julia

The ill effects of having relatively high tax rates can be illustrated in the case of Julia, a public school teacher, holding the position of master teacher 1, in a public school in Manila. She is considering migrating to Hong Kong and working as a domestic helper for a minimum wage for a family of four in Hong Kong.

By simple arithmetic, we can easily see that giving up her teaching job to become a domestic helper is not as difficult as it may seem. Although the gross salary of a teacher is larger, financial gains are larger in Hong Kong because the taxes and other deductions are larger in the Philippines. (See Figure 3.)

With the Asean economic integration taking place at the end of the year, migration of Filipino workers to other Asean countries with lower taxes becomes more imminent.

Narrow tax base

More than one-third of all Filipino households say that they do not pay income taxes.

The 2012 Family Income and Expenditure Survey showed that among households headed by professionals (accountants, lawyers, doctors, engineers, etc.), only 41 percent declared paying any income tax. Households headed by a self-employed nonprofessional, such as an owner of a small business, had an even lower tax compliance. Only 30 percent of them reported paying any income tax at all. On the other hand, nearly 100 percent of all salary workers said they paid taxes. (See Figure 4.)

While it is true that income tax collection from the salary worker is easier, only 28 percent of them are required to pay income taxes. About 72 percent of them are minimum wage earners, and thus, tax-exempt. This means that the base of automatically compliant individual income taxpayers is small. BIR records show that only 5.06 million Filipino workers paid an individual income tax in 2011.

Taxation is not progressive. It is unfair.

Our current tax table seems to suggest that income taxation in the Philippines is progressive. There are seven taxable income brackets, each with an applicable tax rate ranging from 5 to 32 percent. (See Table 1.)

John Lloyd, taipans

However, one wonders why by simply looking at the list of the Top 500 taxpayers, one finds glaring inconsistencies. In 2013, Kapamilya star John Lloyd Cruz paid more income taxes than any of those on the Forbes’ list of top 10 wealthiest Filipinos. One might add: It is hard to believe that Cruz made more money than the 10 richest Filipino taipans.

One problem concerns the P500,000 threshold that defines the top taxpayer. The top tax bracket, because its income cutoff is too low, now puts celebrities, mall owners and taipans together with a public school principal in just one tax category.

Moreover, while the school principal will find it difficult to avoid the income tax (as their taxes are automatically withheld on wages), the owner of a mall can hide behind the veil of corporate taxation plus pay the hefty fees of tax lawyers and accounts in order to legally avoid tax payments. Interestingly, the top tax income threshold of P500,000 had been set as far back as 1950.

Sauce for the goose, but apparently not for the gander

A significant manifestation of inequity in income taxation is that taxpayers, earning the same income, end up paying different taxes simply because of their type of work.

Assuming that they all have the same income, a salary worker will pay substantially more income taxes than a professional or a self-employed entrepreneur. Data show that a salary worker actually pays 28 times more income taxes than the professional and self-employed entrepreneur!

The effective tax rate for the salary worker is higher than those of the rest. To illustrate this point, two individuals with an annual income of P700,000 but with different types of employment have different amounts of actual taxes paid. (See Figure 5.)

Why is this so?

One reason is that tax rules are stricter for the salary worker but more liberal for the professional and the self-employed. Professionals enjoy a myriad of tax deductions not available to salary workers.

Another reason is that while tax evasion is practically impossible for the salary worker, it is rampant among the professionals and self-employed. The complexity of tax procedures for professionals and self-employed has been determined to be one reason for their propensity to avoid tax payments. It is this “complexity,” which businessmen also complain about, that makes the revenue officers more powerful and even whimsical.

Frozen tax brackets

The tax brackets have been frozen since 1997 as these have not been adjusted for inflation. While salaries have been adjusted for inflation and tax brackets have not, salary workers have been pushed into the higher tax brackets and therefore now face higher tax rates.

In 1997, the bulk of salary workers was found in the lowest tax brackets. By 2013, most of them have crept up to the higher brackets without even realizing it. Thus, salary workers pay higher tax rates today even if there has been no real increase in their income.

Bracket creep

This phenomenon of “bracket creep” is more apparent for selected professions, such as teachers and soldiers. In 2001, about 65 percent of teachers were classified in bracket 4. By 2013, only 21 percent remained in bracket 4. Most were shifted up to brackets 5 and 6.

In 2001, 57 percent of soldiers were in brackets 3 and 4, with only 4 percent in brackets 5 and 6. By 2013, only 39 percent were classified in brackets 3 and 4 while 44 percent were in brackets 5 and 6.

What needs to be done

Unfreeze the frozen.

Tax brackets must reflect changes in economic conditions by adjusting them to the inflation rates from 1997 to 2013. The tax brackets should be adjusted in this manner. (See Table 2.)

This new set of brackets would push a considerable number of teachers (54 percent) and soldiers (37 percent) back to brackets 3 and 4, effectively increasing their take-home pay.

While inflation-adjusted tax brackets will reduce tax revenues for the BIR, we should think of this as the price of fairness. A staggered inflation adjustment over time, combined with other tax reforms (as discussed below), could minimize revenue loss. Fairness, can in fact, come without tremendous cost provided that well-designed tax reforms are introduced.

Increase the number of taxpayers through a simple, fair and progressive tax system.

Tax compliance needs to be made simpler. The current labyrinth-like tax forms that an ordinary person cannot understand must go. Tax filing and payment must be made easier and more convenient by allowing more payment systems instead of the current setup.

Our tax system must be perceived as fair. An extremely powerful incentive for paying the right tax is its fairness. When citizens see the tax system to be fair—those who earn more pay higher taxes than those who earn less—there is a reduced tendency for tax evasion (Kirchler 2007 and Falkinger 1988). Conversely, when citizens believe the tax system to be unfair, we expect tax evasion to be rampant.

We hope for a tax scheme that maintains the progressive elements of the current scheme, where the many minimum wage earners are tax-exempt and where the highest taxes are exacted on the superrich. But more importantly, we hope that the rest of the middle class who have successfully avoided tax payments, particularly professionals and entrepreneurs, can help ease the pain of the already burdened salary worker.

Lowering tax rates results in higher tax collections.

We need to lower tax rates for two important reasons. First, to address the concern of reduced competitiveness in a more globally integrated economy. Second, lower income tax rates can actually reduce income tax evasion as shown by a number of studies (Wu and Teng 2005, Crane and Nourzad 1990, Clotfelter 1983). Our statistical analysis suggests that a 1-percentage point reduction in income tax rates predicts a 69- to 72-percentage point increase in the likelihood of tax payments.

Affordable tax reforms.

What happens when we combine all elements of our proposed tax reforms, namely: inflation-adjustment, increasing the income cutoff for tax exemption, adding a top tax bracket for the superrich (those earning at least P10 million), reducing the number of tax brackets, removing personal deductions and lowering the average effective tax rate by 24 percent?

Our simulations show that with at least 90 percent of nonsalary workers paying their income taxes, this package of tax reforms will shift

36 percent of the tax burden to the highest tax brackets. Tax revenues will initially drop and fairness will come at a relatively small price—an initial reduction of 11.4 percent of current tax collections.

This estimated loss already accounts for a portion of workers’ tax savings being spent on consumer items (about 77 percent), which are subject to a 12-percent value-added tax. In the long run, with more jobs created due to a more vibrant Asean economic community and more foreign direct investments due to lower labor costs, the tax base is wider from which more taxes can be collected. (See Table 3.)

How will Teacher Julia gain from this package of tax reforms? She gains because she is reclassified to a lower tax bracket and faces even lower effective tax rates at her new bracket. She saves at least P11,715 per year. She can use this to increase her weekly budget on food or augment the stocks in the family-owned sari-sari store.

Rethink and reform income taxes.

We hope for an enlightened tax administration that seeks to meet its revenue targets by first understanding taxpayer behavior, regularly collecting and analyzing data, and considering collection strategies that increase the tax base and reduce opportunities for corrupt practices.

While the current strategy of increasing the tax burden of those already part of the tax base had initially worked, ultimately it will not. We should unburden the paying salary workers by compelling most of the middle class to share the burden. Taxpayers must be treated as genuine partners in economic development.

With the needed tax reforms in place, teacher Julia faces lower taxes. Hong Kong no longer seems to be as green a pasture as before. We are now more hopeful that she will opt to stay, serving her country as a public school teacher instead of taking care of children—not her own—in Hong Kong.

(Miro Quimbo is the representative of the second district of Marikina, chair of the House committee of ways and means, and principal author of House Bill No. 4829 that seeks to overhaul income taxes. Stella Quimbo, Ph.D. is department chair and coordinator of the health economics program at the University of the Philippines School of Economics [UPSE]. Xylee Javier has a master in development economics from UPSE.)