As the east Asia region urbanizes, so does the importance of Manila, one of the region’s largest and densest “megacities.” But how does the growth of the Manila urban area compare with that of other large metropolises in neighboring countries, or the hundreds of small and medium cities strewn across East Asia?

Until recently, these questions have been hard to answer in a systematic way but advances in satellite technology now allow us to map and measure spatial changes in hundreds of cities at a time, using imagery of the Earth’s surface taken by satellites orbiting the planet.

Changing landscape

At the World Bank, we recently conducted such a study and have recently released our findings in a new report titled “East Asia’s Changing Urban Landscape: Measuring a Decade of Spatial Growth.” Using the results of our satellite data analysis, we can now examine the expansion of the Manila urban area and see how it fits into the larger regional picture.

Any attempt to compare the growth of Manila with other international cities is hindered by the fact that cities are defined differently from one country to another. Even comparing national trends in urbanization is difficult since every country has its own official statistical definition of what it considers “urban.”

While the 2010 census in the Philippines uses a definition based on various factors, including barangay population size and number of employees in individual establishments, other countries base their definitions on population density thresholds, type of employment, or other criteria.

Problematic definitions

These definitions are useful in each of their own countries but clearly they are problematic while trying to compare trends between countries. For our regional analysis of urban change, we wanted to make sure we were comparing “apples to apples” instead of “apples to oranges.” The best way to do this was to create our own map of urban areas across the whole East Asia region.

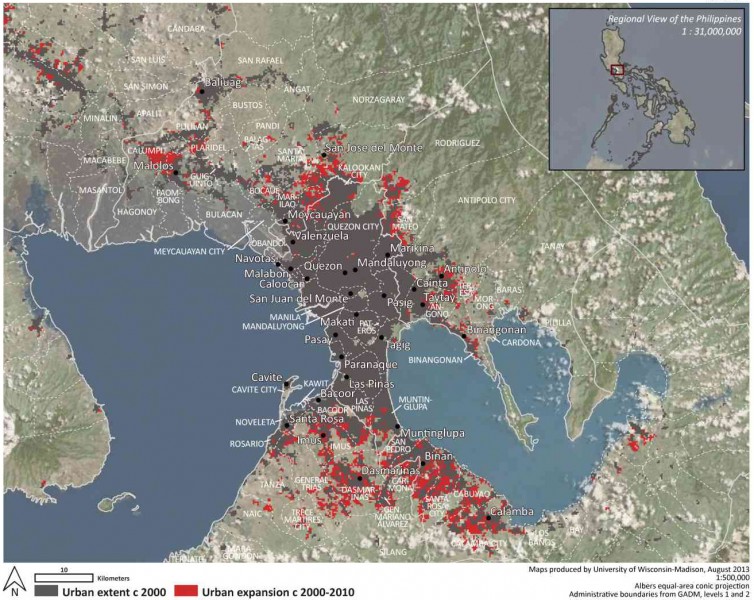

To do this, we worked with Earth observation experts at the University of Wisconsin in the United States to analyze satellite imagery of the surface of the Earth for the years 2000 and 2010. A computer program examined the entire surface of the East Asia region, one 250-meter-by-250-meter grid square at a time and identified all the areas that had artificial land cover.

Satellite data, population

This was then combined with a population distribution map, which used a sophisticated modeling technique developed by the WorldPop group at the University of Southampton in the UK.

The two together allowed us to identify every urban agglomeration in East Asia that had over 100,000 people: all 869 of them. So now, for the first time, we were able to measure and compare urbanization trends across hundreds of cities, from Mongolia to the Pacific islands, in a uniform way.

Manila urban area

Manila is one of East Asia’s “megacities” of over 10 million people, alongside seven others as of 2010. Using the satellite data, we defined the urban agglomeration of Manila based on its built-up footprint, which included not just Metro Manila but also parts of the provinces of Bulacan, Cavite, Laguna, Rizal as well as small amounts of built-up area in Batangas and Pampanga (though we treated Angeles City and its surrounding areas as a separate urban area).

We refer to this as the Manila urban area, to distinguish it from the official definitions of Metro Manila and Mega Manila. We found that the built-up land in the Manila urban area covered nearly 1,300 square kilometers, making it the 12th largest urban area in the region in terms of size. (The largest in the region was the Pearl River Delta urban area in China, which includes a number of cities within it and covered almost 7,000 sq km.)

The Manila urban area’s spatial footprint grew by 250 sq km between 2000 and 2010. This rate of spatial expansion, 2.2 percent per year, was twice that of Bangkok or Seoul, but was nowhere close to the explosive rates of expansion seen in Chinese urban areas like Shanghai or Hangzhou, which grew at 8 to 10 percent per year.

Less than 1 percent of the total area of the Philippines, around 2,300 sq km, was part of urban areas. There were nearly 135,000 sq km of urban land spread across the East Asia region (an area roughly the size of the entire island of Luzon, for the sake of comparison), but that too covered less than 1 percent of the region.

16.5 million in 2010

With over 16.5 million people in 2010, the Manila urban area was the sixth largest in the region by population (after the Pearl River Delta urban area in China, Tokyo, Shanghai, Jakarta and Beijing in that order). The Manila urban area’s population grew by 4.3 million people between 2000 and 2010, which is remarkable considering that a city of over 4 million would be a large city in its own right.

Still, its population growth rate, 3.1 percent per year, was similar to the average growth rate for all urban areas across East Asia (3.0 percent) and slightly lower than the average for all urban areas in the Philippines (3.3. percent).

Counting just the urban areas with populations over 100,000, the Philippines’ urban population stood at 17 million in 2000 and increased to 23 million in 2010. This was the region’s fifth largest urban population, after China, Indonesia, Japan and South Korea but made up only around 3 percent of the region’s total.

East Asia’s total urban population, counted the same way, grew from 579 million people in 2000 to 778 million in 2010. One way to appreciate the scale of this increase of almost 200 million people in 10 years is that, if it were a country on its own, it would be the world’s sixth largest.

Metro Manila generates an estimated 50 percent of the Philippines’ gross domestic product, so it is clear that the country’s economic success rests largely on Manila’s success. It is not just the Philippines’ largest urban area; it dominates the country’s urban landscape. Even though it grew at a slightly slower rate than other urban areas in the country, the Manila urban area still has over half the total urban land in the Philippines and over 70 percent of its urban population, by our definition.

Unlike countries like China and Indonesia, which have a range of secondary cities of various sizes, there is a large gap between Manila and other urban areas in the Philippines. The next largest urban area, comprising the urbanized parts of Metro Cebu, had less than a tenth of the population of the Manila urban area.

While some countries, like South Korea, have prospered with a single large urban hub, there are also potential benefits to having a range of secondary cities that can complement the largest one, each with their own comparative advantages, which would give businesses and households more choice in where to locate and relieve some of the pressure on the primary city.

High density an asset

Manila was also one of the densest large cities in the region, with nearly 12,000 people per square kilometer in 2000, which increased to 13,000 by 2010. This was twice as dense as Tokyo, though Jakarta and Seoul were even denser than Manila. This high urban density was seen in urban areas across the Philippines, which had 10,300 people per square kilometer on average, whereas the regional average was 5,800. In East Asia, only South Korea had denser urban areas than the Philippines on average.

Many readers will no doubt be worried that Manila’s high, increasing density can only mean more traffic congestion and pollution. But this is not necessarily the case. If dense areas are located close to jobs, schools and shops, are well-served by public transportation and are designed in a way that make walking and bicycling easy, density can actually cut down on traffic and lead to more sustainable urbanization.

Also, density can help boost economic growth, through what economists call “agglomeration effects,” e.g. more potential employers and employees in one place, economies of scale in service provision, lower transaction costs, etc. In places like the United States that have very low average urban population densities, planners are struggling to increase densities to create more vibrant, walkable cities.

Manila’s existing high densities may be difficult to manage but are potentially a valuable asset to its environmental sustainability and economic growth.

Challenge of coordination

It is well known that Metro Manila comprises 17 different local governments, making coordination across the metropolitan area difficult. In fact, the scale of the challenge is even larger. If one looks at all the built-up areas in the Manila urban area, they form part of up to 85 different local governments, in the seven provinces listed above.

In fact, less than 40 percent of this total built-up area is within the official boundaries of Metro Manila and almost all the new urban expansion between 2000 and 2010 (94 percent) took place outside Metro Manila. It is clear that a coordinated approach is required to tackle the challenges of this large urban region.

Manila exemplifies an extreme version of this challenge, which we refer to in the report as “metropolitan fragmentation,” i.e. the division of a metropolitan area into different government units.

But it is not alone. Our study shows that around 350 urban areas in the East Asia region have grown beyond local boundaries. A total of 135 of these were similar to Manila, in the sense that no single local government contained even half of the total urban area.

Many large urban areas around the world have tried various arrangements to bring about coordination between local governments across a metropolitan area. For example, some cities like Toronto and Cape Town have consolidated lower tiers of government to create a single metropolitan government.

Others in the United States and Latin America have created organizations to coordinate specific services, like transportation, across metropolitan areas. Many different bodies are involved in providing services to the vast metropolitan area of Tokyo, including a metropolitan government, prefectural governments and various private service providers.

None of these models are universally applicable but the various governments that make up the Manila urban area can draw from international experiences, and adapt them to their institutional and political context.

Vision, spatial strategy

Given these challenges, can Manila ensure a sustainable future? The World Bank has been supporting the Metropolitan Manila Development Authority (MMDA) in developing the “Metro Manila Greenprint 2030,” which aims to build a shared strategic vision for the entire “Mega Manila” urban region.

This involves bringing together various stakeholders, including the governments of all 16 cities and 1 municipality within Metro Manila, along with national government agencies, the private sector, civil society organizations, urban planning professionals and academics.

In Phase 1 of the process, the stakeholders came together through workshops, meetings and learning events, and jointly defined their vision statement for 2030: “Metro Manila for all; green, connected, resilient; offering talent and opportunity; processing knowledge and delivering services at home and abroad.” This vision has in particular incorporated feedback and suggestions from one-on-one consultations with the 17 mayors in Metro Manila.

Greenprint

The Greenprint aims to help foster a “Metropolis of Opportunity,” by leveraging opportunities for IT-BPO, harnessing tourism potential, promoting high-potential economic clusters and other means. The vision outlines ways in which Metro Manila can become green, connected and resilient through a variety of means ranging from developing public transport, upgrading informal settlements and ensuring that Metro Manila is resilient to natural disasters and economic shocks.

The World Bank continues to support the MMDA in developing the Greenprint, convening global expertise to help Metro Manila learn from cities around the world. For example, we have recently invited experts from Guadalajara, Mexico, which has recent experience in building a coordinated metropolitan vision; Curitiba, Brazil, which is famous for its innovations in sustainable urban development; and the Regional Plan Association based in New York, which did a global review of different kinds of metropolitan governance, to explore potential metropolitan management structures that would help Manila urban area deliver its vision.

Inclusiveness, resilience

In Phase II of the Greenprint, we will develop a broad stroke and long-term spatial strategy to help realize Metro Manila’s vision as identified in Phase I. Rather than producing a comprehensive “Regional Physical Framework Plan,” the second phase of the Greenprint will focus on key areas emerging from the Phase I visioning process: connectivity, inclusiveness and resilience.

The World Bank’s Institutional Development Fund will help build MMDA’s capacity and strengthen its role as a metropolitan planning and coordinating body. The World Bank will also facilitate dialogue with key stakeholders and introduce metropolitan governance models from other countries as part of the Global Lab for Metropolitan Strategic Planning.

We are also publicly releasing all the data on urban expansion that were used for our regional urban expansion study, which we hope will help officials and researchers gain an understanding of urban expansion in Manila and elsewhere in the Philippines and benchmark it against the growth of over 800 other urban areas in East Asia. We are confident that all these efforts can help make the growing Manila urban area more sustainable, inclusive and resilient.

(Chandan Deuskar works at the World Bank on urban development issues in the East Asia and Pacific region. He is an author of the recently released World Bank report “East Asia’s Changing Urban Landscape: Measuring a Decade of Spatial Growth.” Yan Zhang is the senior urban economist at the World Bank Manila Office and is leading the World Bank’s engagement with MMDA on the Metro Manila Greenprint 2030.)