Subway to solve Manila traffic woes

Frequent traffic gridlock has traumatized residents of Metro Manila. Dinner guests at a Makati hotel one rain-drenched evening a couple of weeks ago compared notes, with one making a three-hour trip from Parañaque City and another traveling four hours from Balara, Quezon City.

Then on the way home, close to midnight, this motorist is shamed by commuters queued up almost a kilometer long, three- or four-person deep, some under the rain, waiting for their ride home. In just six to seven hours, they will have to start their day again with long queues going to work and long queues going home.

It is the responsibility of the government to provide commuters a decent, dignified and affordable means of transport. This is the least this government can do for these commuters are President Aquino’s “bosses.”

Article continues after this advertisementWorking group

The President should immediately form a special technical working group (TWG) composed of the heads of the Department of Transportation and Communications (DOTC), Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH) and Metro Manila Development Authority to finally do a comprehensive mass transit system capable of handling the volume of commuters not only today but a hundred years forward.

The TWG shall have one single goal: Set the solution in place now, signed and sealed tight, virtually irreversible.

Article continues after this advertisementWith Mr. Aquino and the public works secretary enjoying the people’s high confidence, the public will accept any decision by this administration. This is our golden opportunity. Let’s not squander it.

A major project like this will attract the corrupt in the government, much as what happened to the North Rail and the nuclear power plant under past administrations. Conversely, this game-changing infrastructure can become a good governance success story.

Improved lives

The improvement in the lives of millions of Metro Manila residents, particularly the commuters, and the increase in investor’s confidence can be Mr. Aquino’s legacy.

To plan long term, we need metrics to guide us: What is the ideal number of mass transport kilometers? As an order-of-magnitude indicator, one possible parameter is population per commuter rail kilometer (ppcrk) of the well-managed megacities in terms of traffic flows.

Very roughly, the average among the top cities is about 30,000 ppcrk. With Metro Manila’s 15 million inhabitants, we should have around 500 km of commuter rail in the metropolis.

382 km needed

Our existing 51 km (LRT 1, LRT 2 and MRT 3) plus Philippine National Railway’s (PNR) commuter run of about 29 km (Tutuban to Alabang) plus their planned extension and the almost done MRT 7 total 118 km. We will still need 382 km to approach the norm.

The present 51 km of elevated light rails have all but destroyed the once beautiful and historic Avenida Rizal, Taft Avenue, Aurora Boulevard and even Edsa. To add 382 km or 7.5 times more of elevated-type railways could further “uglify” this former “Paris of the East.”

Aesthetically pleasing

Thus, we are advocating the installation of a heavy-rail mass transport subway network. It will be aesthetically pleasing. It can be set up with least disturbance to the current traffic. Its high capacity and less right-of-way issues make it cost-competitive—even less expensive on a passenger per kilometer basis than the elevated type.

Metro Manila is fortunate to have a subsoil known as Guadalupe Tuff, a type of adobe ideal for tunneling. Finally, subway is the favored solution adopted by many Asian megacities.

Congestion cost

Competent international organizations have estimated the congestion cost at up to P2.4 billion a day, roughly $20 billion a year using such factors as wasted fuel and manpower hours, health issues and foregone business opportunities.

A 2011 subway study estimated its cost at $100 million a kilometer; the tunnel cost at 40 percent or $40 million a kilometer; the 382 km of tube would cost around $15.2 billion.

Even if we assume only 25 percent or $5 billion of the $20-billion cost per year can be saved by the subway system, it will take only three years to recoup the $15.2-billion cost. If the 382 km of rail will bring us first-class city status in traffic, the recovery could be just 1.3 years.

State-owned tube

I am segregating the cost of the tube because I am recommending that it be owned by the government as a public works asset. With a century or more life-span, it will exist in good working condition way beyond any concession period given to public-private partnership participants or way beyond the lives of the present citizens and their children (London’s 150-year-old subway and New York’s 125-year-old system are still in good use). Future citizens should carry some of the burden of this very long-term asset.

Also, being government-owned the winning international tube contractor can perhaps avail itself of official development assistance (ODA) from its home country. With concessional interest rate, grace period (sometimes 20 years) and payment plan of ODAs, we would have recouped the investment before the first amortization.

If the 382 km of new rail is ambitious, as other means of mitigating traffic congestion can also be implemented (like the modified BRT along Edsa I proposed earlier), the government may opt to discontinue after the first 150 km or the second, maybe 20 years down the road. Plans can be scaled down accordingly to realities on the ground.

Our country has been criticized time and again for not spending enough for infrastructure. This could be part of the answer.

Now, why a special TWG? So it can laser focus on this extremely important project for the management of the bidding process. It can do the following:

Hire the best transport and rail planners:

– Determine commuter movements in 10 to 20 years;

– Lay out the definite alignment of the first 150 km, approximate the next 150 km and guess the last 82 km; the first 150 km to be further subdivided into workable segments of 30 to 40 km each;

– Locate optimal sites for subway stations and determine their basic requirements at least for the first 150 km;

Hire top-level consultants to prepare detailed engineering designs for the initial 150 km of tubes and various stations, optimal performance standards, environmental impact, economic and social benefits, value for money, and geotechnical and other technical analyses;

Bid out the construction of the tube under the supervision of the DPWH (based on the results of the first two bullet points), inviting the world’s best tunnel borers who can be supported by their country’s ODA programs, and find ways to tunnel simultaneously from two or more points to achieve quicker relief;

Bid out, with the help of transaction advisers, to rail companies and property developers the development of the stations and the use of properties adjacent to the alignment for ingress and egress; develop opportunities for nonrail revenues, and the operations and maintenance of the rail system.

Happier people

The government will be the biggest beneficiary of smooth traffic flow: happier people with more productive hours, leisure time, quality time with family and fewer health issues.

As a subway system, it would mean higher real estate values in its alignment—meaning higher real estate taxes and more people visiting the places and making local businesses active.

Reasonable fare

The second biggest beneficiary will be the commuters. With no tube cost, the fare will become more reasonable. Less fare cost, less pressure for salary increases, more money to spend.

The rail company with no tube cost will need less borrowing that it can carry on its own balance sheet, needing no government support for its loans. Therefore, the government will have no right to monkey around with the fare, which usually leads to the dreaded government subsidy in the end.

One design

With the government owning all the tubes, the tubes in all sectors of the subway system will be of one design and all subway sectors will seamlessly merge with one another unlike the LRT 1/MRT 3’s planned convergence.

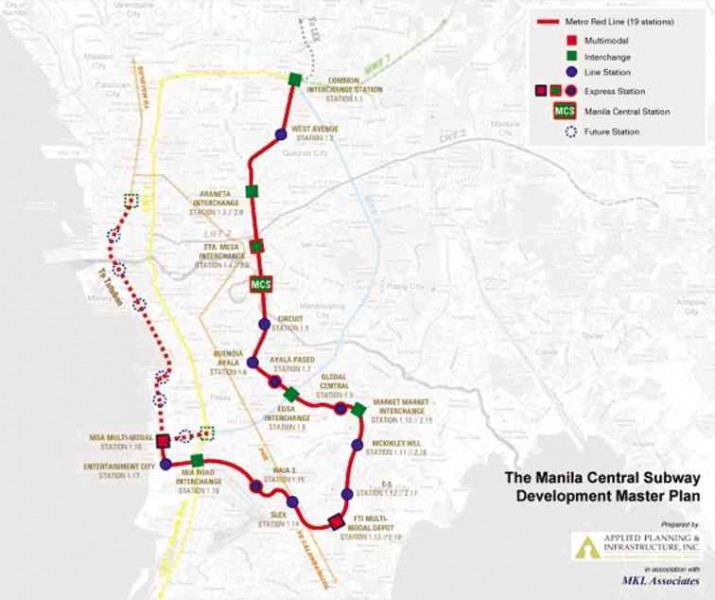

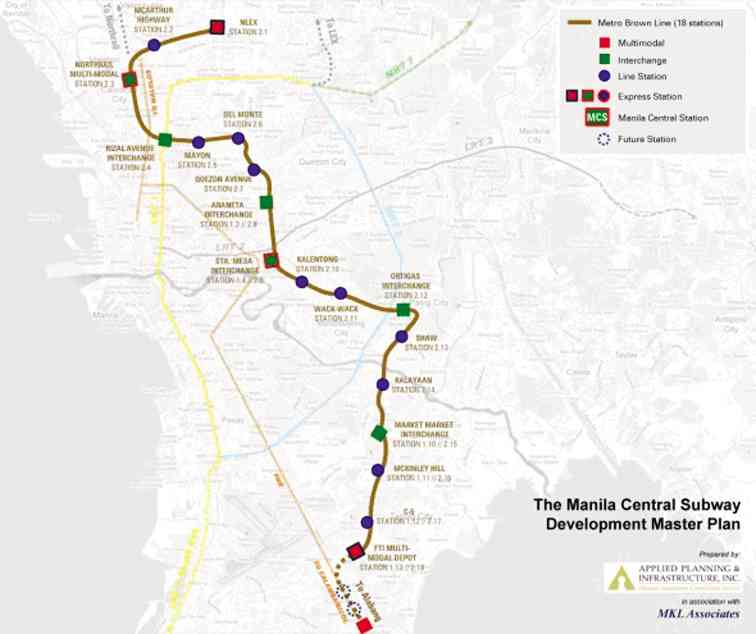

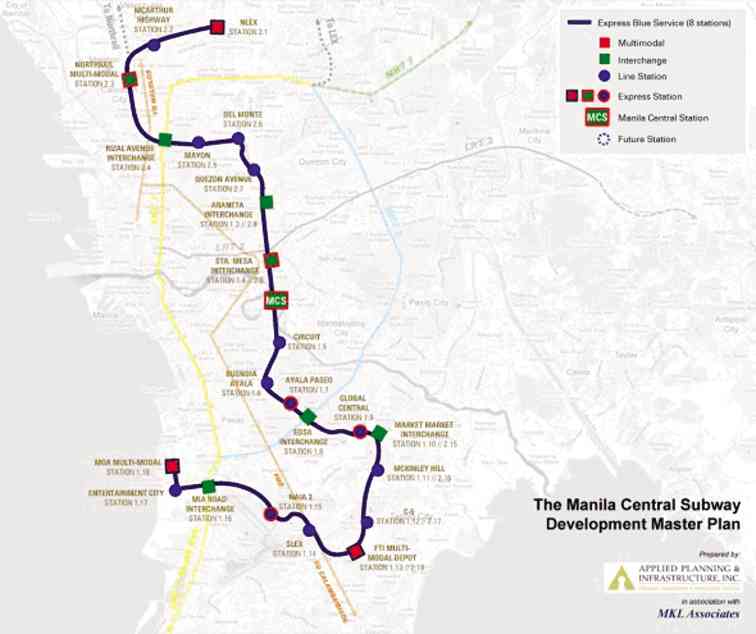

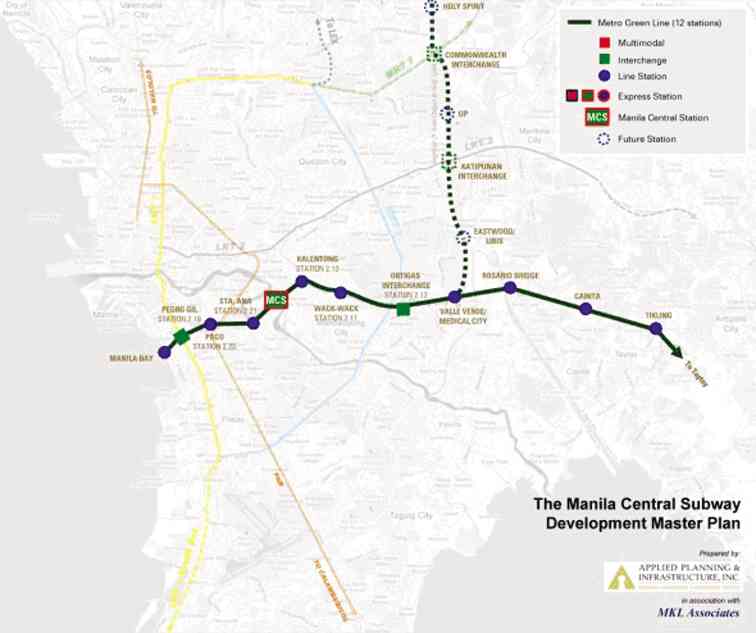

To illustrate how a subway system might look like, here are some results of a decade-long study started by a renowned international consultancy group and continued by its successor local company, Applied Planning & Infrastructure Inc., which generously allowed me to use some of their findings. The result is a business case for the first 33 km of a 125-km system to evolve within the next two decades or, hopefully, shorter.

North-south orientation

Several traffic studies show that the high priority is a north-south orientation along some of the highest population density areas of the old part of Manila, Quezon City, Taguig City and San Juan City to connect to where people work—the central business districts of Makati City and the new Global City.

This alignment will require a massive underground rail backbone capable of transporting 80,000 people/hour/direction equivalent to 1,300 buses per hour. It will carry more than double the current MRT 3 load.

Recent reports show that the DOTC favors an east-west orientation. While this alignment may eventually be necessary, it will probably be much later on, maybe past 2030. Even LRT 2, which has an east-west orientation, has not even reached its design capacity while the north-south MRT 3 and LRT 1 are already bloated.

Dream plan

Even Japan International Cooperation Agency’s “dream plan” advocates a subway underneath Edsa, which has a north-south orientation. But Edsa is already saddled by MRT 3 and thousands of buses and even more cars and trucks.

Concentrating more transport on Edsa may not be the best solution. This is why our north-south suggestion is located more in the center of the megalopolis where the bulk of high-density population areas is concentrated.

It will also relieve MRT 3 of much of its overload. About 85 percent of ridership is driven by home-to-workplace demand. If a station can be installed within 1-km radius from their homes and offices, people will be attracted to use this subway.

Multimodal interchanges

Multimodal interchanges would connect the system to North Luzon Expressway (NLEx) and PNR in the North and Global City, Food Terminal Inc. (FTI) and South Luzon Expressway (SLEx) in the South, decongesting the Edsa/MRT 3 corridor.

Here is how the alignment might look like:

It will start from FTI where the big, largely unused property of PNR is located. This would be ideal for a depot-cum-bus stops, where provincial buses and other feeder buses and jeepneys can have their depots. It has enough area for huge parking spaces for the park-and-ride commuters.

From FTI, it will have stops at C5/Taguig; Global City; Edsa-Ayala; Ayala/Paseo; Buendia/Ayala; old Sta. Ana; Kalentong/Shaw; Sta. Mesa (to meet LRT 2); Araneta/España Extension; Araneta/Quezon Avenue; Quezon Avenue/West Avenue; North Avenue/Edsa area (to meet MRT 3 and the future MRT 7).

Then, it will further extend to Congressional Road and NLEx, and to SLEx, Ninoy Aquino International Airport and Mall of Asia. Then it will eventually connect Quezon Avenue to Del Monte, Mayon Street in La Loma then Rizal Avenue to connect to LRT 1 to the proposed North Rail exchange then to MacArthur Highway to the north depot. (See metro red, brown, express blue and green lines on this page.)

The red line alignment serves as a parallel route from Ayala/Edsa to Edsa/North Avenue, unburdening some loads off MRT 3. It will also relieve some pressure from LRT 1 and LRT 2.

Station entrance

How will a typical station entrance look like? (See photo.)

Notice that all you see are the entrance to and exit from the subway station. The station will, of course, take into consideration the history of floods in each area, say the 100-year highest flood level adjusted to the latest climate changes.

Forward 50- to 100-year design for the network is necessary even at this stage to handle the crisscrossing of different lines, all based on the traffic count of where and what time commuters are taking the ride and where they will disembark.

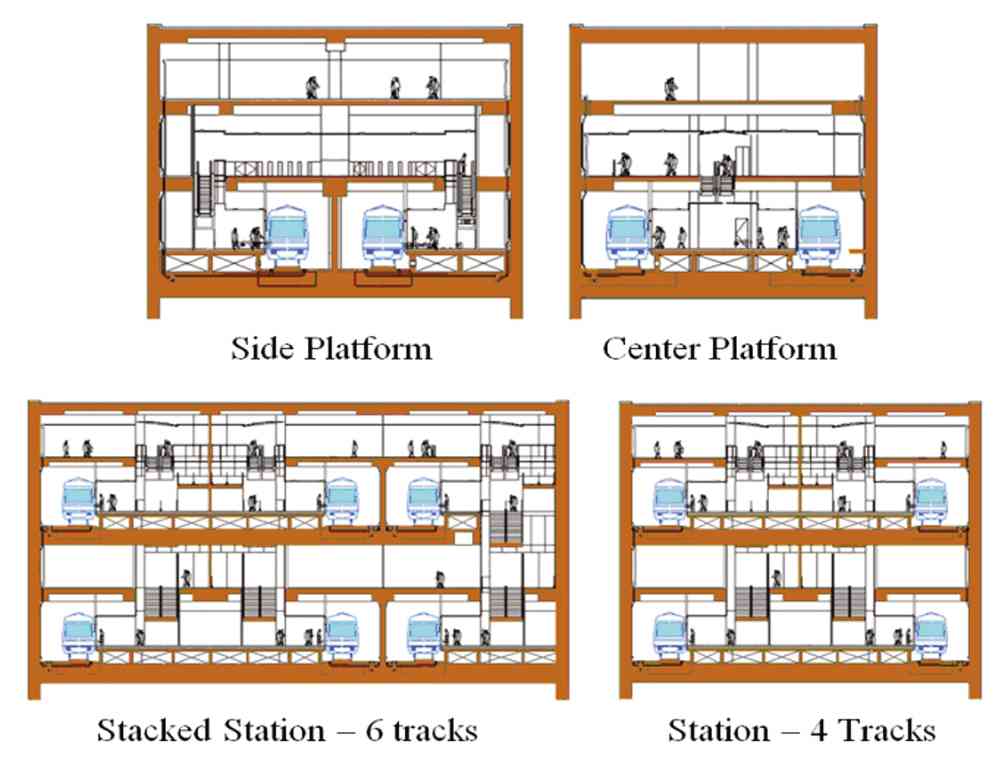

This comprehensive study will determine how the intersecting trains will crisscross one another to determine the optimal design of stations. (See sample cross-section designs.)

Finally, some people worry about earthquakes. Other cities with miles of subways are much more earthquake-prone than Manila. It is just a matter of engineering and route selection to avoid active fault lines.

It will cost a little bit more to design and build the tunnels when passing near suspected active faults.

Metro Manila is fortunate to have an ideal subsoil condition. It sits on Guadalupe Tuff, a type of adobe that is ideal for tunneling.

(Glicerio V. Sicat, a Department of Science and Technology consultant and a senior adviser to Applied Planning & Infrastructure Inc., was an investment/development banker, part-time professor at Ateneo MBA Program and a former transportation undersecretary. He holds a BSME degree from University of the Philippines Diliman and an MBM from Ateneo.)