Asean financial integration

As a financial services professional, I applauded the signing into law of Republic Act No. 10641. Here was finally a concrete step toward the promise of further integrating the Philippines into the global economy and benefiting from it. That would be a massive step forward for us.

We need to look back a mere five years to see how far we’ve gone as a country in terms of perception.

Global financial crisis

It was 2009 and the world was undergoing a global financial crisis. Back then, I was a product head for a foreign bank and I was pushing for the launch of a lending product that would use Philippine government securities as collateral—fairly vanilla as bank lending goes, and from all financial and commercial aspects it was very low risk.

After all, the only way the bank would really lose money on the transaction was if the perfect storm happened: The client would need to default on its debt, the bank would need to fail to claim on the collateral and the national government would have to default on its bonds.

Of course, this perfect storm was possible (and with the negativity in the world in 2009, the fear was there) but it was highly unlikely.

I was in a product development meeting and we had a foreign risk manager on speakerphone, and he was the deciding vote whether to launch our product. My team did its homework well. We researched the historical valuations of Philippine debt over the last 20 or so years and we rigorously applied our financial models. Given the low-risk nature of the collateral, we knew that the product would be a winner.

Low credit rating

Unfortunately, the meeting was not going anywhere. Despite all our proposals, evidence and tons of mathematics, his answer was simple: “Sorry, we will not be lending against Philippine debt. Your country’s credit rating isn’t investment grade.”

That statement frustrated me no end back then since we at the Manila office all knew that the financial crisis was centered on the United States and Europe— Asia and the Philippines were largely unaffected. Because we were working in a foreign bank, we had to abide by our foreign risk-appetite.

To the global community, the timing to launch any new lending product was inappropriate given the prevailing crisis and the perception then of the Philippines was negative.

Investment grade

Fast forward to five years later, the world has started to recover from the 2008 crisis, Asia is an attractive investment destination and the Philippines has been officially acknowledged as investment grade by the global rating agencies.

With its membership in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean), the Philippines has also started on its journey to become a player in the global economy. How I would love to be in that product meeting again today and have that debate with the foreign risk manager!

(As a matter of trivia, that particular risk manager was actually from Greece, which in hindsight is doubly ironic given what transpired in Europe a few years later.)

But let’s stop it there for a moment. Not everyone is a banker and not everyone appreciates what RA 10641 means to the average banking customer.

In a JWT consumer survey conducted last December with respondents across the Asean member-states, less than three out of every five respondents from the Philippines were aware of the Asean Economic Community (AEC) and its 2015 deadline.

Among the Asean respondents, Filipinos were the most upbeat that the AEC would benefit the region as a whole. Of those surveyed who said they were aware, three out of four were optimistic that the move would benefit the Philippines specifically but most respondents were unaware of any changes that would happen in 2015.

Full entry

RA 10641 allows full entry of foreign banks in the Philippines. The act is an amendment to Republic Act No. 7721 that was passed in May 1994, which allowed foreign ownership of up to 60 percent of an existing bank or subsidiary but limited the entry to one entity.

Under the new law, foreigners may own up to 100 percent of an existing bank or a new bank subsidiary and may also open up to five sub-branches.

Allowing foreign bank entry is also means to encourage investment, as foreigners will be more comfortable bringing capital into the Philippines through banks more familiar to them.

Road map

The new law is consistent with the vision of the AEC expected to come about in 2015. Financial integration is a key component of the AEC blueprint, which envisages integrated financial and capital markets in the region by 2015.

The blueprint’s road map for monetary and financial integration includes the following initiatives:

Financial services liberalization. Progressive liberalization of financial services by 2015 (RA 10641 supports this).

Capital account liberalization. Removal of capital controls and restrictions to facilitate freer flow of capital.

Capital market development. Construct long-term infrastructure for the development of Asean capital markets, intending to achieve cross-border collaboration between various markets in the region.

The passage of RA 10641 is hopefully the start of what will be a broader move toward further liberalization. However, achieving adequate readiness for Asean financial integration will not be achieved by a single law.

Despite the credit rating upgrades received by the Philippines from international ratings agencies (S&P, Moody’s and Fitch) in the months leading to the World Economic Forum in Manila last May, business leaders were still skeptical on the readiness of Philippine banks and industries to Asean integration.

Banking framework

Local bankers also expressed concern that smaller banks would get edged out with the entry of the larger foreign players.

In its 2013 report on Asean financial integration, the Asian Development Bank (ADB) cited three characteristics as essential to an Asean banking framework:

Equal access. Promotes the active penetration of the regional banking market by Asean-based banks. (RA 10641 is a step in this direction.)

Equal treatment. Similar risk assessment and profile across various member-states.

Equal environment. Harmonization of regulations, accounting standards, disclosure requirements and capital requirements.

According to ADB, of the three it is harmonization or uniformity of regulations across the Asean that will be a daunting task given that the member-states are at various levels of economic development.

Basel 3

For example, implementation of the regulations under the Basel 3 Accord varies across the region: In the Philippines, the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas is only about to announce which Philippine banks are classified as

D-SIB (domestic systemically important banks), which will be subject to tighter capital rules.

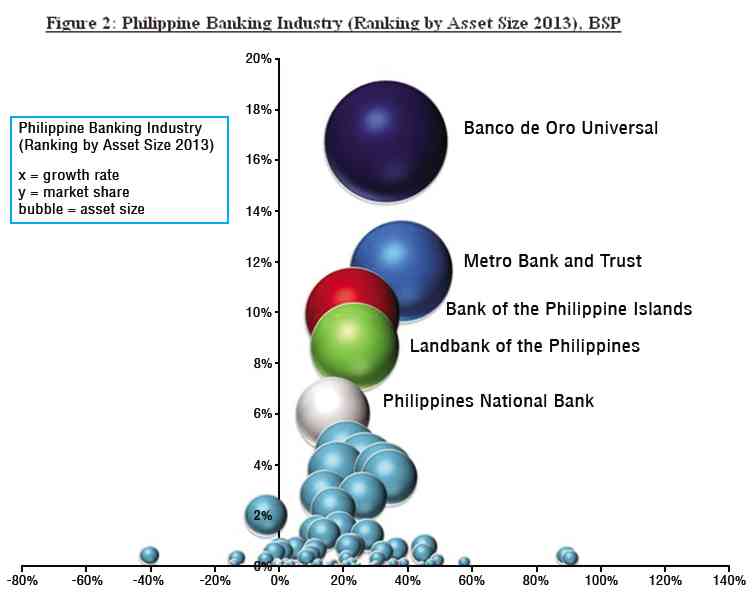

In its current state, the Philippine banking industry has a lot of participants (already numbering more than 200 banks, even excluding the rural banking sector), with the majority of the banking assets concentrated in the top five players. (See infographic.)

Although some foreign banking players have existing licenses, their collective local presence remains small relative to the industry— something which will soon change as regional players move quickly to capitalize on the new law.

Promise, risks

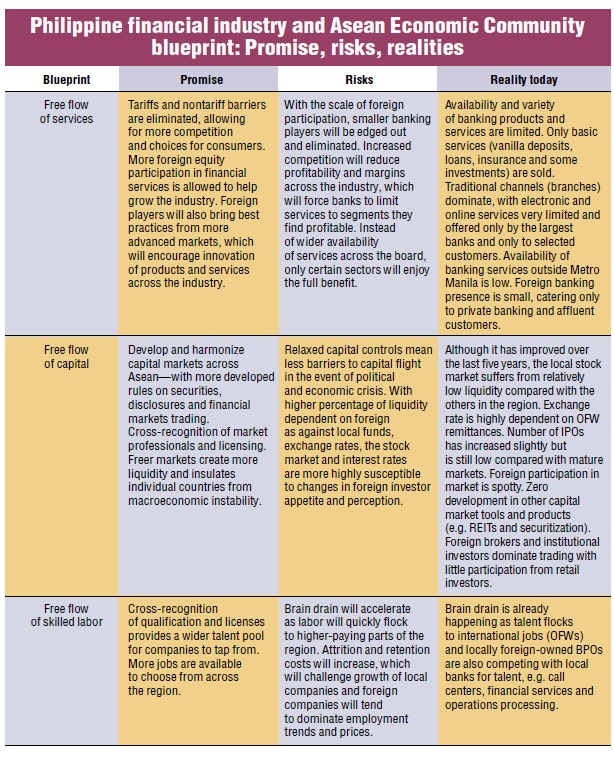

The AEC blueprint holds a lot of promise for the local financial industry, especially in the areas of services, capital markets and labor, but integration will carry its set of risks. For the general banking public, the reality is that the current state of the local industry is backward relative to the region and innovation cannot happen without the help of foreign participation.

Banking practices in the Philippines for most banks have not changed much since the introduction of automated teller machines in the 1980s. Apart from the credit card industry, which is quite competitive due to the presence of some foreign players, most banking products offered locally like deposits, loans and investments are generic. They have very little differentiation and are rarely on flexible terms to customers.

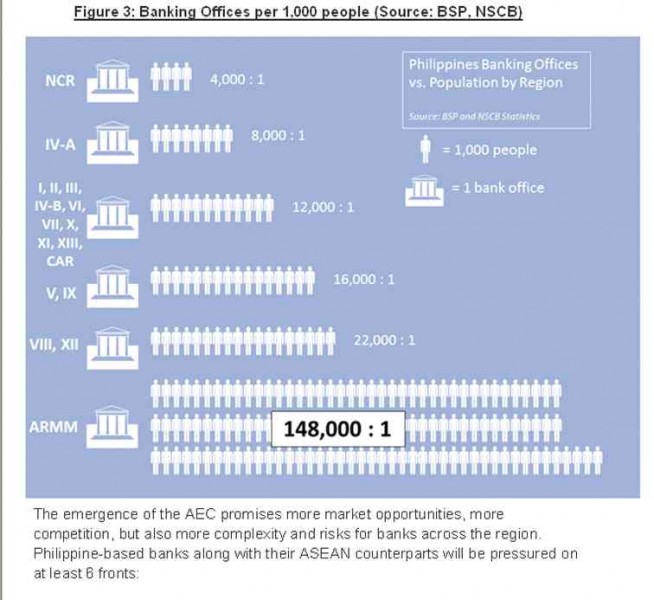

Physical availability of banking is also concentrated in Metro Manila (National Capital Region) and nearby areas, and drops off very quickly the farther you go from the capital. For example: the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao is the least serviced, with only one banking office per 148,000 people. (See infographic.)

More competition

The emergence of the AEC promises more market opportunities and more competition but also more complexity and risks for banks across the region. Philippine-based banks along with their Asean counterparts will be pressured on at least six fronts:

1. Talent and skills. As competition heats up, the banks will experience the staffing challenges that business process outsourcing firms have had over the past decade as a liberalized sector with foreign competition can inflate costs in recruitment and retention of key talents.

2. Risk appetite and business strategy. Banks well acclimated and calibrated to their local markets will now have to adjust their lenses to a wider market and competition across the region.

3. Business intelligence and analytics. Regional market competition will benefit agile players who have a good sense of their data and business drivers, and are able to monitor their key performance indicators but at the same time will penalize slower ones who have poor data and siloed, inaccurate information.

4. Capital efficiency. With a regional market, the impact of capital regulations brought about by Basel 3 and multijurisdiction capital requirements (harmonized or not) will challenge return on equity and favor banks with an ability to assign and deploy adequate amounts of capital.

5. Technology. Competition will tend to bite into margins and challenge revenue growth, so the ability to squeeze cost efficiencies through automation, information technology and rapid execution of business strategy is critical.

6. Governance. Amid heightened competition and complexity, banks will still need to maintain strict controls and risk management. This cannot be done in a reactive manner in a faster-moving and regionally integrated economic environment.

This can all happen very quickly once foreign participation increases across the banking sector as a whole, which will pressure local players to pursue innovations to remain competitive.

Digital banking

For example, one area of promise is in digital banking. Modern innovations in online and mobile transactions have provided alternatives to physical locations for other consumer activities like travel and shopping—e.g. consumers can easily book hotels and flights, order books and shop online—but the digital channels in banking remain quite limited, especially in the Philippines.

According to a recent study among European banks (McKinsey and Co.) where the digital banking trend is only starting to gain momentum, the typical challenges for digital channels that banks usually cite include fraud, risk, money laundering and regulatory requirements. This is true for the Philippines as well, where online and mobile channels are not maximized for banking services.

Banks that adopt digital transformation will not just be able to realize operational efficiencies through the automation of services and less reliance on physical locations. The convenience of online and mobile banking will also be a major differentiator for customers in their preference for banking services, according to the same study.

Impact on customer

This finally brings us to the most important question: What does RA 10641 and AEC ultimately mean for the average banking customer? The answer is: nothing on their own. Not unless the banks themselves and the industry act to change the status quo.

Changes in regulations have been touted as the major obstacle to any innovation but with the passing of RA 10641 and hopefully more reforms to come, the private sector will have to work hand-in-hand with regulators to implement the new laws.

Even with the entry of foreign banks as a likely trigger, some laws have been in existence for some time but adoption and implementation have been slow.

For example, Republic Act No. 9510, or the Credit Information System Act, was put into law in 2008 to create the country’s unified credit bureau but has only started to get traction this year. The E-Commerce Act has been around since 2000 and yet only the largest commercial and universal banks have a working online presence.

Good start

RA 10641 is a good start but the reality is it is quite late in the game. The AEC deadline in 2015 and Philippine elections the year after that do not leave a lot of time for local banks to wake up and adjust to the new reality.

The challenge is not just to the banking system to adapt and innovate to the times but also to the consumer to drive change through smarter choices and feedback. In the age of social media, more and more power has shifted to the customer. The banking arena will not be any different.

(Dominic Ligot is a consultant at Teradata Philippines LLC covering the financial services industry. He lectures on data-driven marketing, enterprise risk management, finance and industry regulation. Before going into consulting, he held executive roles in foreign banks.)