Violence after Moro deal

Many doubt if the recurring violence from armed rebellion can be reversed by the signing of the Comprehensive Agreement on the Bangsamoro (CAB) between the Philippine government and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF)

Yet it already has.

Few people realize that the negotiation period saw the marked decline in rebellion-related or vertical violence attributed to the MILF. A ceasefire has been in place between the Philippine government (GPH) and the MILF for more than a decade.

Article continues after this advertisementDespite the brief episodes when violent flash points erupted in 2003, 2005 and 2008, the truce has largely endured, creating the space and generating the momentum to achieve a comprehensive peace accord.

We owe this to the patience and flexibility of the Office of the Presidential Adviser on the Peace Process and the negotiating panels of the GPH and MILF, plus the mediation efforts of the Malaysian-led International Monitoring Team.

So should we now rest in the afterglow of this peace compact? The public should be cautioned against the dangers that lurk behind press statements about the advent of a lasting peace in Mindanao. The evidence from the Bangsamoro suggests that horizontal violence—a term often used to describe inter and intraethnic violence, and inter and intraclan feuding, or political contestation—will likely grow as rebellion-related conflict recedes.

Article continues after this advertisementThe significance of the peace agreement really rests upon its ability to curb these other sources of violent conflict.

Increased conflict

International Alert UK (Alert), with the support of the World Bank, established in 2013 a Bangsamoro Conflict Monitoring System to monitor conflict incidence over time in the region and adjacent provinces.

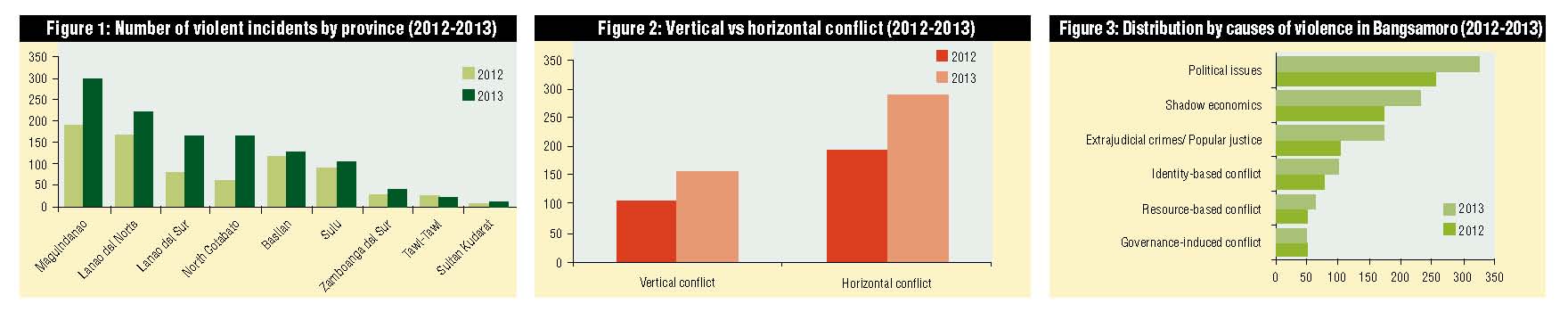

In partnership with Mindanao State University and Western Mindanao State University, police blotter, spot and progress reports, combined with media reports of violent conflicts, were gathered to generate data showing that horizontal violence increased from 2012 to 2013 in the Bangsamoro. (See Figure 1.)

No boundaries

Conflict incidence was largest in the mainland provinces of Maguindanao and Lanao. The adjacent provinces of Sultan Kudarat and North Cotabato were included because conflict knows no boundaries and violence often spills over to adjacent areas, or victims and perpetrators came from areas outside the Bangsamoro.

Among all the provinces in the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao, only Tawi-Tawi registered a decline in violent incidents during this period. These trends coincide with the holding of the midterm national elections and the barangay elections in 2013, the violent confrontation between the government and the Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters in the central Mindanao region, and the clashes between the government and Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) fighters in Zamboanga City.

Horizontal conflict

Most of the violence arose from horizontal conflict. (See Figure 2.)

The past decade saw conflict incidence in the Bangsamoro shifting from rebellion-related violence toward horizontal violence and armed contestation between clans, ethnic groups, political elites and shadow authorities.

The evidence reveals basic truths that stare us in the face—one, that any reduction in rebellion-related conflict as a result of the CAB can lead to lasting peace if the agreement helps resolve cases of horizontal conflict, and two, that working on horizontal conflict should be a priority for the new Bangsamoro government and peace builders alike.

ZAMBOANGA CONFLICT Government troops take their positions in the standoff with MNLF fighters in September last year. EDWIN BACASMAS

Multicausal

There are many sources of horizontal conflict in Mindanao but most of these emerge from political conflicts. Distinct from rebellion-related violence, political contestation refers to the sort of violence that springs from elite contests for elective and nonelective positions at various levels.

These violent contestations plus resource disputes over land, minerals and other natural resources provide the basic elements within horizontal conflict.

Land is a critical issue that needs to be urgently addressed. Many violent flash points in the past 10 years have been the result of violent rivalries over land masquerading as rebellion-related conflict as warring clans sought the intervention of the MILF or the military in support of their land claims.

Meanwhile, conflicts over mining claims or the allocation of royalties guaranteed to indigenous peoples who grant free, prior and informed consent to various extractive companies have also triggered conflict in Mindanao.

More importantly, the evidence also suggests that an important source of violence are those fueled by shadow economies, or the violence that erupts from struggles for control of these economies, including illegal firearms and drug trade, cattle rustling, kidnap-for-ransom and gambling (See Figure 3.)

Indeed, violent conflict in Mindanao is often multicausal. One example is the assassination of Mayor Ocol Talumpa of Labangan, Zamboanga del Sur, and his wife that occurred in full view at the entrance to Ninoy Aquino International Airport Terminal 3 last December.

Police reports indicate that a long-running clan feud, coupled with political contestation and the shadow economy in illicit drugs in his hometown, was the likely motive behind the fatal attack.

Violent strings

Violence also comes in “strings,” or as Nikki Philine de la Rosa (“Violent Strings in the Bangsamoro: Disrupting the Flow of Conflict.” Alert UK Thematic Paper, 2014) puts it “violence often come in pairs, or in sets of three or four.”

Community-level conflict can easily morph into rebellion and criminal violence and endure for decades in the form of clan feuds.

So, instead of looking at singular acts of violence, one should investigate strings of violence when analyzing Muslim Mindanao and explore how to interrupt or disrupt these strings of violence.

Addressing these realities should have been high on the agenda of the peace panels. However, the CAB and its annexes contain few provisions that tackle these “strings” or the likely increase in other sources of violent conflict.

For example, the wealth-sharing and political-power-sharing agreement devolves the registration and reclassification of land, but is silent on the means for dispute resolution and the role of traditional, yet legitimate institutions for land management.

Land disputes

Land disputes may intensify with the return of ex-combatants or the internally displaced to their former communities and find the hostility of current land occupants waiting for them.

The CAB neither includes any provision that grants ex-combatants, including women and children identified with armed groups, access to home lots or cultivable land.

The annex on normalization talks about the decommissioning of weapons and combatants, but the schedules for weapons decommissioning are unclear. The proposed time frame for accomplishing the decommissioning of weapons does not match the demobilization of MILF ex-combatants, leading many to suspect that a fully armed MILF will remain a feature of the Bangsamoro before and after the plebiscite and the regional elections in 2016.

Even more problematic is the fact that the normalization annex was superseded by a new gun law (Republic Act No. 10591), which makes it easier to procure guns and carry these outside residences.

Transition-induced

There is also a growing concern among conflict specialists about the phenomenon of transition-induced violence, or the tendency for violent conflict to erupt as various groups play out their rivalries in the interim period between the signing of the agreement, the short term of the MILF-led Transition Authority, and the creation of the Bangsamoro government.

It can also rear its head in the early normalization or liberalization period that follows the redeployment of military forward units away from Muslim Mindanao’s conflict areas.

Transition-induced violence is manifested in the reiteration and restoration of land claims by former refugees who wish to return to their land as the violence subsides. There is the real risk of factional fighting among MILF combatants and between the MILF and other rebel groups, as the evidence in Aceh, Indonesia suggests.

Blood debts

Clan feuds can intensify as local strongmen take revenge on those with blood debts during the long years of conflict.

Finally, there are threats of armed conflict between ruthless political entrepreneurs staking claims on political offices to be created under the new Bangsamoro.

Expect these new conflict triggers to be pulled during the transition period. There have been many cases in the past where revenge killings accompanied a transition, or an intensification of forced abductions and kidnap for ransom that are less about the financial rewards and more about embarrassing incumbent political authorities and their inability to provide protection to ordinary citizens.

There is also the genuine threat of exclusionary provisions and fundamentalist ideas landing in the basic law if the dominant Muslim minority falls prey to the temptation to flex or overstretch its muscle.

Liberal peace

Transition-induced violence has been a recurring theme in studies of conflict transformation. They often erupt when long-suppressed ethnic or religious rivalries and dormant resource conflicts boil over in the aftermath of liberalization or democratization.

Fears over new rounds of violence underscore the criticism against the prescription for a “liberal peace”—characterized as a textbook menu that promotes elections and plebiscites, the imposition of good governance rules and the restoration of basic freedoms.

Without ample preparation, this playbook can produce an election that leads to majority rule that ignores the desires of the minority, press freedoms used to spread racial hatred and incendiary messages, and the freedom to organize and protest used to foment targeted violence against vulnerable groups as in the case of Rakhine state in Myanmar.

Worse, imposing a “good governance” regulatory regime at the outset can penalize poor rural producers who depend upon coping economies with little regulation by the state.

In short, fears of an eruption of rebellion-related violence seem farfetched. Instead, the sort of conflict that can spoil the onset of a lasting peace will most likely come from Mindanao’s warlord clans and local strongmen, political elites and criminal entrepreneurs.

Credible guarantees

The World Bank conflict specialist Nigel Roberts has written about the need for clear “signals of future intent,” or credible guarantees that need to be demonstrated by the government and the MILF in the transition process. He cited the need for affirmative actions that can draw other political elites and rebel contenders (MNLF) into the governance process.

To this, we add the need (a) to demonstrate a commitment to a secular state, (b) to recognize the people’s voice as the only determinant in redrawing the boundaries of the new region, and (c) to provide clear evidence of a willingness to deal with other sources of violence, including those that emanate from clan institutions.

These guarantees should be front and center of any viable communications strategy that seeks to win support for the Bangsamoro basic law in Congress.

Decommissioning

Dealing with the issues of land and weapons decommissioning, two of the most contentious issues, will determine the acceptance of the agreement by a broader section of Mindanao society. To this end, it is time to announce a clear time frame for decommissioning and to establish a Bangsamoro Land Commission that can serve as a dispute-resolution body that can immediately deal with land issues.

Mr. Aquino was spot on when he swore to defend the hard-won peace against those who would dare snatch it away. He should probably watch HBO TV’s new season of “Game of Thrones” to understand that this is easier said than done. It is the best imagery one can summon to understand the intransigent violence and resilient power of Mindanao’s clans.

(Francisco Lara Jr. is Philippine country manager of International Alert UK. He is the author of “Insurgents, Clans and States: Political Legitimacy and Resurgent Conflict in Muslim Mindanao,” [2014] Quezon City, Ateneo de Manila University Press.)