Infrastructure and Filipino women

QUEUING FOR WATER Women wait in line to fill their containers with water at a deep well pump in Barangay Batasan Hills, Quezon City. RAFFY LERMA

The scarcity and poor quality of physical infrastructure in the Philippines are much lamented and with good reason.

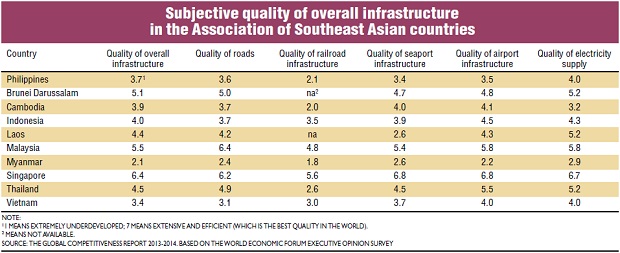

The Philippines is classified as a middle-income country in the 10-member Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean). Yet, the quality of its infrastructure is ranked the third lowest in the Asean, regrettably lower than that of its lower-income neighbors Cambodia and Laos. (See table.)

Article continues after this advertisementPoor-quality infrastructure is particularly evident in its seaports and airports, which are great disappointments for the nine million overseas Filipino workers, who back home are considered “heroes,” a status that must be accorded, at the very least, convenient and clean port facilities.

It is well-known that our international airport in Manila is considered one of the world’s worst airports in terms of convenience and access, whereas airports in neighboring Hong Kong and Singapore are among the best.

In terms of quality of electricity supply and road network, the Philippines ranks, again, the third worst in the Asean. As to railroad, our facilities are comparable with those of Myanmar and Cambodia. Ironically, the Philippines was the first to build a light railway transit in Southeast Asia, regarded a milestone three decades ago.

Article continues after this advertisementRural infrastructure, such as irrigation, farm-to-market roads and postharvest facilities, are largely fragmented and never seem to constitute a good complementary package of inputs to our small farmers.

Reasons for handicap

Why this handicap in infrastructure? Inquirer columnist Cielito Habito, former socioeconomic planning secretary, gave several reasons

—lack of public funds, frequent damage caused by typhoons and floods, and corruption in government construction projects.

Indeed, because of a lack of budget (mainly because of low tax revenue collection), the national government spends only 2.8 percent of the country’s gross domestic product on infrastructure, which is far below the World Bank’s 5 percent recommendation to enable the Philippines to meet its infrastructure needs in the coming decade.

Thus, at this point, we could not expect much of an improvement in our infrastructure.

Wide disparities

There are wide disparities in infrastructure stock across regions in the country, with Metro Manila getting the lion’s share. For example, the metropolis has an almost exclusive monopoly of good roads and close to 100 percent of its households have electricity and running water connection.

Many Filipinos believe that our inadequate infrastructure is due to underinvestment. The only significant investments done by the private sector were in the power and water sectors from around the mid-1980s to the mid-2000s. But then, several crises hit the power sector in the 1990s, which seem to have lessened early initiatives from the private sector.

Progress in telecoms

The telecommunications sector is where we can observe major progress mainly because of the platform first laid out by the Ramos administration to achieve a more competitive telecommunications system.

At this point, there is an apparent need for the private sector to assume a greater role in providing infrastructure, given the ever increasing fiscal constraints that limit the capacity of the public sector.

The government therefore should provide an enabling policy environment for greater private sector participation in infrastructure provision.

What determines the allocation of physical infrastructure? Currently, the bulk of infrastructure budget goes to our main urban center, Metro Manila. This is true also in many developing countries as cities are considered the engine of growth where scale economies of infrastructure could be fully explored.

Density, paved roads

In the Philippines, population density determines the extent of electricity coverage and the length of paved roads. It is thus not surprising that towns near Metro Manila, such as those located in the densely populated and progressive provinces of Cavite, Laguna, Batangas, Rizal and Quezon (Calabarzon) and those near Metro Cebu benefit from regular electricity supply and good-quality roads.

Political considerations also matter because highly populated areas produce a large number of voters. This translates into having more representatives in Congress, more pork barrel and still more “congressional favors.”

Being a country made up of more than 7,000 islands, infrastructure development may prove daunting in provinces consisting of many islands.

Jobs

For example, in Sulu, which has 222 islands, the proportion of households with electricity is only 30 percent compared with almost 100 percent in landlocked Calabarzon. This substantiates the difficulty and high cost of connecting the small islands to the main electricity grid in areas with a high number of widely dispersed islands.

Does infrastructure create jobs? Physical infrastructure is one of the strongest predictors of entry of new firms. Electricity, for example, enables the formation and growth of small and medium enterprises (mainly in retail and services), creating jobs for the poor. Worldwide, across firms of varying sizes, one of the most important constraints to formal private sector businesses is power supply.

The availability of electricity has induced an expansion of job-employment opportunities in export-oriented sectors in the Philippines. Thus, electricity tends to increase household income from the trade, transport and communication sectors, which employ a large number of the rural poor.

Power shortage

Because of the importance of electricity in economic activity, Socioeconomic Planning Secretary Arsenio Balisacan has raised concerns about an imminent power crisis because of unexpected spikes in demand for electricity emanating from the economy’s robust growth.

Expansion of rural roads could stimulate the growth of the rural transport sector, which connects the hinterlands to local towns and cities, increasing the mobility of goods and services, and providing jobs to people living in remote areas.

Improved roads in the southern Tagalog region have facilitated the emergence of subcontracting arrangements between urban traders and rural firms, most importantly in the garment industry, which largely employs female workers.

Discouraged workers

Does infrastructure induce labor market participation? The Philippines, which has the third poorest quality of infrastructure in the Asean, has, incidentally, the third lowest labor market participation of the working age population between 15 and 64 years old.

This means that the country has a lot of discouraged workers and full-time housewives. Discouraged workers are simply those who gave up searching for a job, discouraged from doing so by many months of disappointing job search.

Historical experience in developed countries in the 20th century shows that time-saving infrastructure, such as electrification and running water, enabled women to produce routine housework at a lower cost.

These time-saving innovations changed the composition of women’s work with less time for preparing food and cleaning the house, and more time for shopping and managing household tasks.

In the middle of the 20th century, participation of women in market work is related to higher appliance ownership (e.g., washing machine and microwave ovens), which is induced by access to electricity.

Good roads give women far greater access to job opportunities by reducing travel time and increasing mobility. Infrastructure matters a lot in inducing Filipino housewives into joining the job market.

In our research, we found that women’s participation in the job market is sensitive to the availability of infrastructure, such as the length of road, and access to electricity and running water.

Educational attainment

What factors affect the decision of a housewife to engage in a job? Educational attainment is the most important factor. More educated women have a higher probability to be on the job because their time is more valuable. Yet, we need to know why labor market participation of females in the Philippines is lower in spite of the fact that Filipino women are more educated than most of their Asean counterparts.

The number of children is another factor—women with a larger number of young children below the age of 5 are more likely to be confined at home because they bear the brunt of housework and care activities.

Filipino women, on average, have 3.1 children, which is the second highest among Asean countries, next only to Laos 3.2. Six out of every 10 women at working age are not engaged in market work and are not looking for a job because of housekeeping responsibilities.

The remaining four are not in the labor force because they are going to school and most of the rest think it is because of their age (they feel too young or too old to be working) or permanent disability.

Income effect

Household income likewise affects the decision of women to work—a woman belonging to a wealthy household (perhaps, the husband has a high salary) is more likely to withdraw from the labor market because of the so-called “income effect” (which simply means that she can afford to have more leisure time).

Yet, richer Asean countries such as Singapore and Thailand have higher female labor-force participation rates than the Philippines. So why are Filipino women left out of the labor market?

We believe that the current state of our infrastructure explains part of the story. Our roads are limited (i.e., our road density is less than 10 kilometers per square kilometer of land area) and are in bad condition (only about 25 percent of our road network is made of concrete and asphalt).

There is also a skewed distribution of paved roads that favor regions in Luzon, such as Metro Manila (i.e., about 100 percent of roads are paved), Ilocos, Central Luzon, southern Tagalog, and Bicol. Central, Eastern and Western Visayas have longer paved roads than Mindanao but these are shorter than Luzon’s.

Roads increase women’s access to economic opportunities by reducing travel time between home and workplace and by increasing mobility as women tend to choose jobs on the basis of distance and ease of travel.

Roads bring in jobs as firms tend to locate in areas with easy access to local and international markets. Indeed, the experience in Bangladesh reveals that rural roads with better quality have increased female labor supply. Bangladesh has a booming garment industry, employing 3.6 million workers (80 percent of them are females) and generating $13 billion worth of exports every year.

The 2009 data from the Family Income and Expenditure Surveys and Labor Force Surveys conducted by the National Statistics Office show that access to electricity and running water have positive impact on the proportion of Filipino females that are employed.

Electricity coverage has expanded across the country (i.e., the proportion of population with access to electricity rose from 47 percent in 1985 to 81 percent in 2009), but the quality of service remains to be desired—frequent brownouts create additional burden on housework and care activities.

Running water

Running water remains a dream for many of our women in far-away provinces who, for many years, spent hours and hours every day to fetch water. Metro Manila and nearby provinces, such as Laguna and Bulacan (more than 90 percent of their population) have higher access to running water compared with those farther away such as Lanao del Sur (less than 30 percent of its population).

Sadly, water provision is a task commonly delegated to young girls, depriving them of time to study school lessons at home. To move forward, we need to build more infrastructure and improve their quality in order to reduce the burden of domestic responsibilities on Filipino women and encourage them to engage in market work, thus enabling us to achieve our national goal of sustaining the currently high economic growth rate.

(Jonna Estudillo is a professor at the National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies [Grips] in Tokyo, while Geoffrey Ducanes was a visiting scholar at Grips early this year. Ducanes is an assistant professor at the School of Economics of the University of the Philippines in Diliman, Quezon City.)