Cash-crop condominiums

When we tell the stories of our wealthiest men, we tend to tell the stories that are of no consequence: We repeat their names, which have generally remained constant for most of recent memory; we futilely recite the numbers of their net worth; and we mythologize the secrets to their success.

When we tell the stories of our wealthiest men, we tend to tell the stories that are of no consequence: We repeat their names, which have generally remained constant for most of recent memory; we futilely recite the numbers of their net worth; and we mythologize the secrets to their success.

These stories are of no consequence for the simple fact that we are telling ourselves things that we either already know, or things we don’t need to know.

When we dwell on who the 10 Filipinos on Forbes magazine’s 2014 list of world billionaires are, we learn nothing of value. Henry Sy’s net worth is a few hundred million dollars lower this year, the Ayalas are mysteriously absent, the majority of the names are Chinese-Filipino. So what?

Significance

But once we turn our attention to understanding what the richest Filipinos are, an entirely different story reveals itself. The true significance of the recent fortunes of our 10-millionth percent is in how their stories can help make sense of the puzzles of our recent economic successes, such as jobless growth, our inability to address deep and widespread poverty, or whether the near future holds an East Asian-style “takeoff” in the Philippines.

To tell this other story, we need to ask different questions: How are the biggest Filipino capitalists building their fortunes? Why, in the Philippines of the 21st century, is wealth being built in this way? How does this strategy compare with those seen in other periods of our economic history, or in other places? Finally, what does the success of this strategy mean for the prosperity not just of the few, but of the country as a whole?

The more things change …

Let’s begin by describing what Philippine capital isn’t. Seen in historical perspective, one thing is immediately clear—the biggest and most successful Filipino capitalists of today aren’t the caciques, taipans and crony capitalists of yesteryear.

Cash-crop export, the bulwark of the landed cacique class, has been in terminal decline for 40 years. A a series of crises—beginning with the end of privileged access to the US market for our sugar exports in 1974, depressed world prices for sugar and coconut in the early ’80s and the mismanagement of monopolies created during the Marcos regime—has steadily eroded the viability of this modus operandi.

Net agri importer

More recently, commitments entered into by the Philippines under the World Trade Organization, as well as in bilateral and regional free-trade agreements have rendered Philippine agriculture susceptible to competition from cheaper, often subsidized, agricultural imports.

As a consequence, we are running an agricultural trade deficit with 11 out of our 16 free-trade “partners,” have been a net agricultural importer since the mid-’90s and our agricultural products have dwindled to less than 1 percent of our total exports.

Domestic manufacturing has fared just as badly. The tariff- and quota-based protection schemes erected to develop a domestic industrial capability, upon which the taipan class had built its wealth, have been dismantled by three decades’ worth of structural adjustment and trade liberalization.

State-owned enterprises, set up as nuclei for Philippine industrialization, have been privatized without even fulfilling their original mandate. Meanwhile, the crony capitalists who ran them were mostly unable to leverage dictatorial largesse into lasting dominance over the economy. Factories, plants and in some cases entire industries were shuttered in the ’80s and ’90s, even as the tiger cub economies of Southeast Asia rode a wave of Japanese investment to industrialization.

And while the Philippines did succeed in developing an export-oriented electronics industry in its special economic zones (SEZs), participation by domestic capital has been insubstantial—other than, of course, in the development and administration of the zones themselves.

Structurally impossible

All told, it is now structurally impossible for Philippine capitalists to amass fortunes on either the backs of peasant labor or from a protected domestic market. With some exceptions, they have not developed the competencies for export-oriented industrialization. They now find themselves in a situation that stands in stark contrast to the ’50s and ’60s, when the wealthiest Filipinos were almost invariably sugar barons and when the upper echelons of Philippine politics were drawn from their ranks.

This situation is also markedly different from the ’70s and early ’80s, when an ersatz industrial capitalist class propped up by the Marcos regime dominated the economy. Finally, it also bears no resemblance to the high-tech, export-oriented “tiger economy” envisioned by the high priests of neoliberal reform in the ’90s.

Yet, they are obviously doing quite well. How?

Back to land

Land, which has long been the most important reservoir of money and power in Philippine society, has reemerged as the cornerstone of Philippine capital’s strategy for the 21st century. But instead of tobacco, sugarcane and coconuts, the new cash crops are condominiums, office towers and malls.

The new Philippine economy is seeing billions of dollars churned into the land by overseas Filipinos buying new homes, services outsourcing firms renting office space and mall operators cashing in on the newfound consuming power of the globalized middle classes.

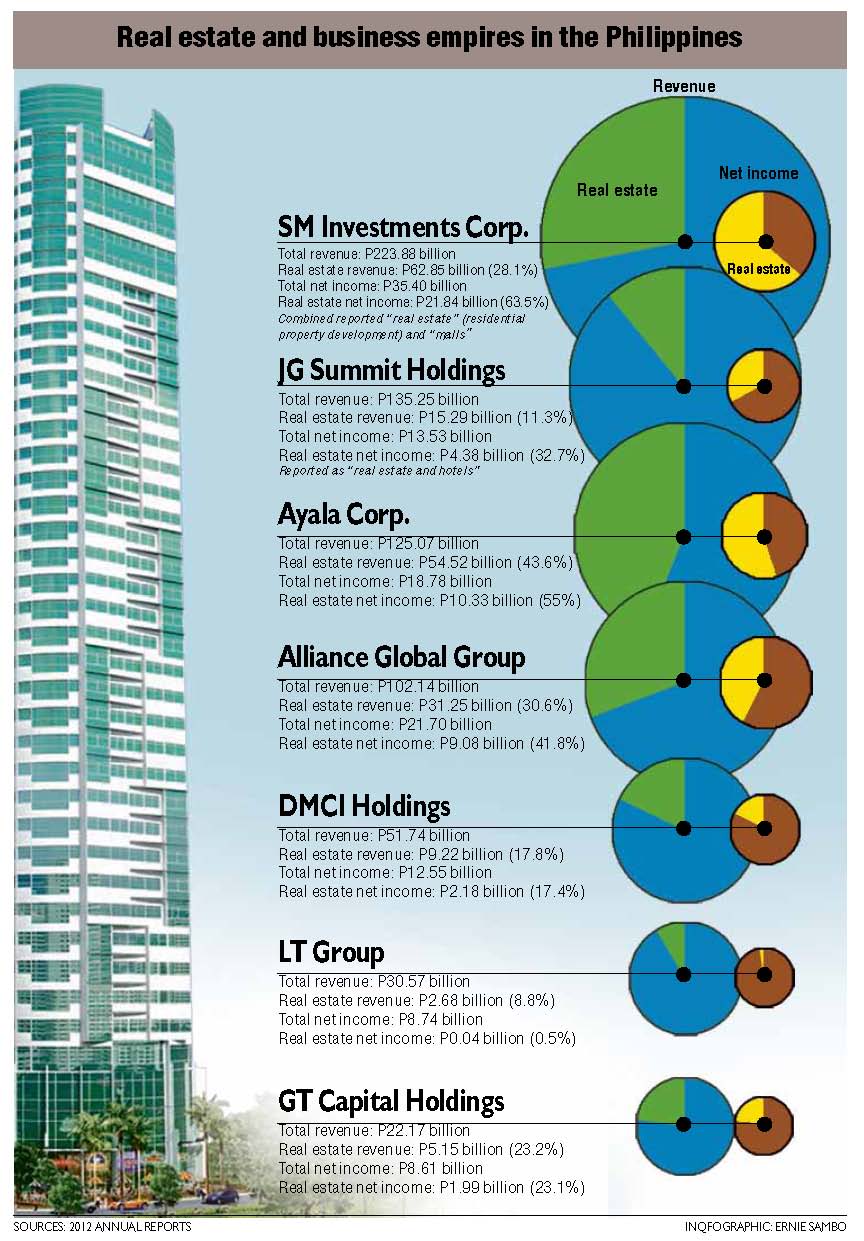

Much of this growth, in turn, was captured by the big, family-owned conglomerates that dominate the economy. They have converged on urban real estate as a strategy for diversifying from their mainstay businesses. Indeed, among the 10 Filipinos on Forbes’ 2014 world’s billionaires list, nine have significant stakes in real estate. (See table.)

Most of the real estate companies owned by the richest Filipinos are fairly new to the game. Only Andrew Gotianun (Filinvest), Manuel Villar (Vista Land and Lifescapes) and Jose Antonio (Century Properties) built their fortunes on real estate, while the rest had zero or minimal interests in property development until recently. And despite being new entrants, these conglomerates have demonstrated a remarkable savvy for it.

SM Development, which began developing residences in 2003, is now the largest property developer in the country. Megaworld, the second-largest developer, completed its first project in 1994. By 2011, it held 13.1 percent of the market. In many cases, their property development arms now outshine the rest of their portfolios, delivering outsized shares of their net incomes. (See infographic.)

Creative destruction

If their fluff profiles are to be believed, the success stories of our capitalists are a simple matter of sipag at tiyaga (industry and patience), business acumen and favorable alignments of the stars. But perhaps it is Shiva, the Hindu deity of creative destruction, to whom our billionaires really owe their recent good fortune. The same forces of neoliberal reform that rendered the old strategies unviable were also creating new opportunities for wealth creation.

The mass exodus of Filipino workers unable to find jobs in our structurally adjusted homeland would eventually grow into a multibillion-dollar-remittance powerhouse.

The aggressive perks granted to economic zone locators and the eventual relaxation of rules that allowed single buildings to be declared information technology SEZs created demand for greenfield industrial zones in southern Tagalog and office space for service outsourcing locators—first in Manila’s business districts and then to “next wave” cities across the archipelago.

Liberated from old economy

Finally, thousands of hectares of urban and peri-urban land, whether in the form of privatized state assets, rice fields deliberately idled by their owners and reclassified to avoid agrarian reform, or brown-field sites of shuttered factories, silos and warehouses, were being liberated—sometimes violently from farmers and the urban poor, often at an unfair price to the Filipino people—from the old economy.

At this point, the prize was simply theirs for the taking. Unlike other sunshine industries, such as electronics manufacturing—or, to a lesser extent, services outsourcing—the technical barriers to entry for property development are minimal, especially if competencies in construction, sales and marketing, and banking were previously developed. Yet, other barriers ensured that only a very select few could salvage the flotsam from the old economy.

The first major barrier is the ability to marshal large sums of capital that was necessary to bid successfully for large, winner-take-all privatizations, or to snap up large tracts for “land banking.” This insulated these companies’ operations from competition from smaller firms.

Limited foreign ownership

But perhaps the decisive advantage to these conglomerates, whether by accident or by design, was conferred by the national patrimony provisions of the 1987 Constitution, which limited foreign ownership of private land to 40 percent of total equity. They were thus protected not only from smaller domestic competitors but also from the more significant threat of foreign capital.

The same logic goes some way to explaining the pattern of diversification that we are seeing among our biggest conglomerates. The sectors that have attracted intense investment by domestic capital, such as banking, retail, airlines, energy, infrastructure, retail, utilities, and most recently, hospitals and schools, are all afforded some measure of protection from foreign competition, and involve businesses that are beyond the reach of most Filipino entrepreneurs.

Lest this be read as an argument in favor of the total relaxation of foreign ownership restrictions: It is not. If anything, the success of Philippine capital in building empires in sheltered sectors should be interpreted as a vote of confidence for the state intervening to create “national champions,” the globally competitive, export-oriented firms that were key to the economic miracles of East Asia.

Indeed, some of the businesses that have thrived under protection have emerged as unlikely and unintentional national champions: SM malls, which began expanding internationally in 2001, and Cebu Pacific, which is the third-largest low-cost carrier in Asia.

‘Keiretsu’ or ‘chaebol’

But will our national champions deliver the same kind of economic transformation seen in Japan and South Korea? In other words, if they aren’t caciques or taipans, are they keiretsu or chaebol?

It matters that much of our recent growth has been in property development and that Philippine capitalism has gone back to the land, because not all forms of economic growth have the same implications for the development—or maldevelopment, or even underdevelopment—of the country.

For industrial capitalists, the two main rules are keeping the rates of profit high and preventing gluts in the market. At the risk of gross oversimplification, Japanese and Korean capital had a stake in thoroughly industrializing their economies and creating a strong middle class because they needed both a cheap and efficient supplier base to keep costs down and consumers to buy their products.

In contrast, property capitalists need to create liquidity out of land, an inherently illiquid, immobile asset, fixed in space and (by virtue of its long turnover cycle) in time. As a breed, they have no vested interest in a large, well-paid industrial workforce. What they do need is to find high-margin markets with quick turnarounds and to ensure that their investments can be readily converted into liquid and globally mobile financial assets.

As luck would have it for Philippine capital, the high-margin, quick-turnaround markets (overseas Filipinos and services outsourcing) exist, are delivering seemingly insatiable demand and are paying in dollars. It also happens that their real estate operations have strong intraconglomerate ties with their banking operations, allowing money made in the property boom to be circulated into other speculative investments, both in the country and overseas, at a moment’s notice.

Casino capitalism

So, at least for the time being, they can let it (chips) ride. But as the recent global crisis demonstrates, casino capitalism is a risky game: Bubbles can pop, assets can suddenly devalue and flighty portfolio investments can evaporate overnight. These possibilities have been detailed elsewhere, and bear no repetition here. Instead, we need to devote attention to even more disturbing possibilities, hinted at by the incongruity between the success of Philippine capital and our impressive headline figures on one hand, and the seeming intractability of joblessness, hunger and destitution that many Filipinos face on the other.

Consider the following: Do the recent successes of Philippine capitalists mean that they neither need to industrialize our economy nor to develop a large middle class in order to turn handsome profits? Do their foreign expansions and acquisitions mean that they can go gallivanting in overseas markets without the need to reinvest wealth in our society? Under these conditions, can the Philippine economy really take off?

Told in these terms, the success of our billionaires makes for an even more incredible tale. The story of what our capitalists are—lurking between the lines of the reverential biographies, the lifestyle section prattle and the junk food statistics—is the story of the domestic capitalist class reinventing and reasserting their power, despite the erosion of their traditional bases of accumulation, despite their failure to transition into export-oriented manufacturing and despite conditions of persistent, grinding misery for the majority of Filipinos.

(Kenneth Cardenas, formerly an assistant professor of sociology at UP Diliman, is a Ph.D. student in human geography at York University, Toronto, studying the big business of building cities in the global South. An expanded version of this analysis will appear as a chapter in the forthcoming book, “State of Fragmentation,” to be published by Focus on the Global South.)